“It has been said, not truly, but with a possible approximation to truth, that in 1802 every hereditary monarch was insane.” — Walter Bagehot

“It has been said, not truly, but with a possible approximation to truth, that in 1802 every hereditary monarch was insane.” — Walter Bagehot

Jokes from the Dust Bowl:

The drought was so bad that when one man was hit on the head with a rain drop, he was so overcome that two buckets of sand had to be thrown in his face to revive him. Housewives supposedly scoured pans clean by holding them up to a keyhole for sandblasting, and sportsmen allegedly shot ground squirrels overhead as the animals tunneled upward through the dust for air. Some farmers claimed that they planted their crops by throwing seed into the air as their fields blew past and that birds flew backwards to keep the sand out of their eyes.

In 1935 Dalhart Texan editor John McCarty founded a Last Man’s Club in which each member took an oath: “In the absence of an act of God, serious family injury, or some other emergency, I pledge to stay here as the last man and to do everything I can to help other last men remain in this country. We promise to stay here till hell freezes over and skate out on the ice.”

As a joke he proposed to build a huge hotel amid the dunes north of Dalhart where tourists would pay “fancy prices” for the privilege of witnessing the “noble grandeur an imposing beauty of a Panhandle sandstorm.” “We’ve got the greatest country in the world if we can just get a few kinks straightened out,” he wrote. “Let’s keep boosting our country.” About 100 people joined the club; more said they wanted to do so but acknowledged they were afraid they’d have to leave.

(From R. Douglas Hurt’s The Dust Bowl: An Agricultural and Social History, 1981.)

interturb

v. to disturb by interrupting

In late 1908 Douglas Mawson, Alastair Mackay, and Edgeworth David left Ernest Shackleton’s party in hopes of discovering the location of the South Magnetic Pole. On Dec. 11, while Mackay left the camp to reconnoiter, David prepared to sketch the mountains and Mawson retired into the tent to work on his camera equipment:

I was busy changing photographic plates in the only place where it could be done — inside the sleeping bag. … Soon after I had done up the bag, having got safely inside, I heard a voice from outside — a gentle voice — calling:

‘Mawson, Mawson.’

‘Hullo!’ said I.

‘Oh, you’re in the bag changing plates, are you?’

‘Yes, Professor.’

There was a silence for some time. Then I heard the Professor calling in a louder tone:

‘Mawson!’

I answered again. Well the Professor heard by the sound I was still in the bag, so he said:

‘Oh, still changing plates, are you?’

‘Yes.’

More silence for some time. After a minute, in a rather loud and anxious tone:

‘Mawson!’

I thought there was something up, but could not tell what he was after. I was getting rather tired of it and called out:

‘Hullo. What is it? What can I do?’

‘Well, Mawson, I am in a rather dangerous position. I am really hanging on by my fingers to the edge of a crevasse, and I don’t think I can hold on much longer. I shall have to trouble you to come out and assist me.’

I came out rather quicker than I can say. There was the Professor, just his head showing and hanging on to the edge of a dangerous crevasse.

David later explained, “I had scarcely gone more than six yards from the tent, when the lid of a crevasse suddenly collapsed under me. I only saved myself from going right down by throwing my arms out and staying myself on the snow lid on either side.”

Mawson helped him out, and David began his sketching. The party reached the pole in January.

No one knows whether Andrew Jackson was born in North Carolina or South Carolina. The border hadn’t been surveyed well at the time.

In short my dear Friend you and I have been indefatigable Labourers through our whole Lives for a Cause which will be thrown away in the next generation, upon the Vanity and Foppery of Persons of whom we do not now know the Names perhaps. — The War that is now breaking out will render our Country, whether she is forced into it, or not, rich, great and powerful in comparison of what she now is, and Riches Grandeur and Power will have the same effect upon American as it has upon European minds.

— John Adams, letter to Thomas Jefferson, Oct. 9, 1787

In 1794, at Strasbourg, the French Hussar François Fournier-Sarlovèze challenged a young man to a duel and killed him. When his fellow officer Pierre Dupont de l’Étang denied him entrance to a ball on the eve of the funeral, the fiery Fournier challenged him to a duel. The two fought with swords, and Fournier was wounded.

When he had recovered he challenged Dupont to a second duel, and wounded him. In their third meeting each inflicted a slight wound on the other. Finally the two agreed to a private war that would continue until one of them confessed that he was beaten or “satisfied.” They even drew up a contract:

Over the ensuing 19 years the two fought at least 30 duels, each eventually rising to the rank of general. Finally, after a particularly savage meeting in Switzerland in 1813, in which Dupont ran his sword through Fournier’s neck, Dupont explained that he would be married soon and wanted to conclude the matter with a pistol duel in a nearby wood. Dupont twice tricked his opponent into firing at empty clothing, then advanced on him with pistols primed and claimed his victory. In The Duel, Robert Baldick writes, “Thus ended after a total period of nineteen years, the longest, friendliest and most mobile duel in history.”

(This story is so absurdly romantic that I doubted whether it happened at all, but every source I can find confirms at least the essentials. Joseph Conrad found an account of the rivalry in a provincial newspaper and turned it into his 1908 short story “The Duel,” and Ridley Scott turned Conrad’s story into the 1977 film The Duellists. I’ll keep digging.)

When British forces plundered the palace of Indian prince Tipu Sultan in May 1799, they found an infuriating trophy:

In a room appropriated for musical instruments was found an article which merits particular notice, as another proof of the deep hate, and extreme loathing of Tippoo Saib towards the English. This piece of mechanism represents a royal Tyger in the act of devouring a prostrate European. There are some barrels in imitation of an Organ, within the body of the Tyger. The sounds produced by the Organ are intended to resemble the cries of a person in distress intermixed with the roar of a Tyger. The machinery is so contrived that while the Organ is playing, the hand of the European is often lifted up, to express his helpless and deplorable condition.

Tipu had allied himself with France against the encroaching East India Company, and the Fourth Mysore War brought his downfall. The tiger, it appears, had symbolized his defiance of British colonialism. The instrument was removed to London, where it became a centerpiece in the Company’s Leadenhall Street gallery; John Keats saw it there and immortalized it in The Cap and Bells, his satirical verse of 1819:

Replied the Page: “that little buzzing noise,

Whate’er your palmistry may make of it,

Comes from a play-thing of the Emperor’s choice,

From a Man-Tiger-Organ, prettiest of his toys.”

“Indeed, the horrific image of a wild beast attacking a helpless fellow Briton must have stirred strong reactions in the British audience so few years after the brutal Mysore campaigns,” write Jane Kromm and Susan Benforado Bakewell in A History of Visual Culture (2010). “Contained within one wondrous work of art was an illustration of the intensity of resentment toward European imperialism, the ferocious power of the enemy prince, and the moral justification for colonization.”

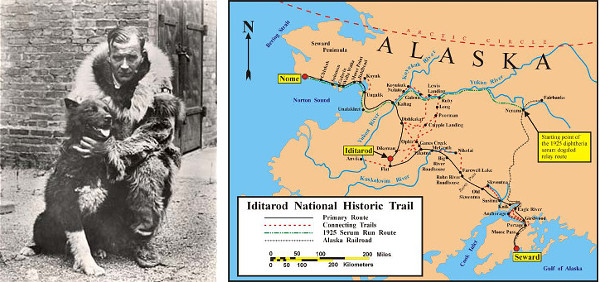

In 1925, Nome, Alaska, was struck by an outbreak of diphtheria, and only a relay of dogsleds could deliver the life-saving serum in time. In this week’s episode of the Futility Closet podcast we’ll follow the dogs’ desperate race through arctic blizzards to save the town from epidemic.

We’ll also hear a song about S.A. Andree’s balloon expedition to the North Pole and puzzle over a lost accomplishment of ancient civilizations.

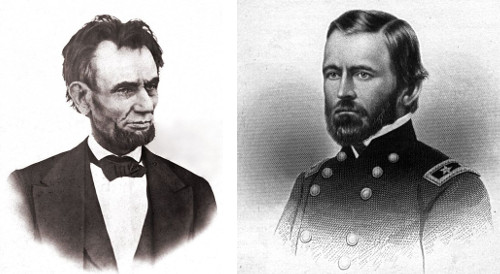

During the drive on Washington city in July 1863, Confederate sharpshooters were unknowingly presented with a particularly high-value target. Captain Robert E. Park wrote: ‘The sharpshooters and the Fifth Alabama, which supported them, were hotly engaged; some of this enemy, seen behind their breastworks, were dressed in civilians’ clothes, and a few had on linen coats. I suppose they were “Home Guards” composed of Treasury, Post Office and other Department clerks.’ Park’s ‘Home Guards’ were in fact President Abraham Lincoln and his retinue, who had left the White House to inspect the defences around Washington. A doctor standing a few feet away from Lincoln was hit, and only prompt action by a nearby Union officer in throwing the president to the ground prevented a sudden and dramatic change in the course of Civil War history.

— John Anderson Morrow, The Confederate Whitworth Sharpshooters, 2002

[After the Battle of Belmont,] Grant went into a cabin and lay down on a sofa to rest, but he was there only a moment. He got up almost immediately to see what was happening on deck. As he rose a musket ball cut cleanly through the boat’s wooden side and splintered the head of the sofa where he had been lying. And still we waste ink and paper in trying to prove that there is no such thing as luck!

— W.E. Woodward, Meet General Grant, 1928

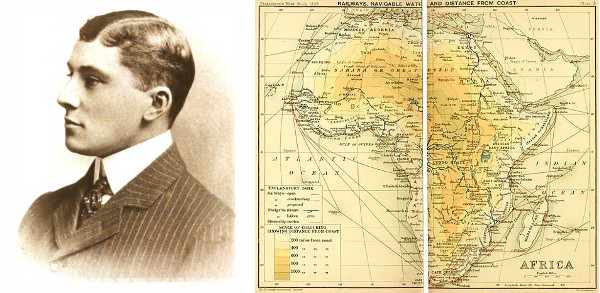

When Ewart Grogan was denied permission to marry his sweetheart, he set out to walk the length of Africa to prove himself worthy of her. In this week’s episode of the Futility Closet podcast we’ll find out whether Ewart’s romantic quest succeeded.

We’ll also get an update on the criminal history of Donald Duck’s hometown, and try to figure out how a groom ends up drowning on his wedding night.