In 1525, fed up with robbers and highwaymen on the Anglo-Scottish border, Archbishop of Glasgow Gavin Dunbar composed a monumentally comprehensive curse against them:

I curse their head and all the hairs of their head; I curse their face, their brain, their mouth, their nose, their tongue, their teeth, their forehead, their shoulders, their breast, their heart, their stomach, their back, their womb, their arms, their legs, their hands, their feet, and every part of their body, from the top of their head to the soles of their feet, before and behind, within and without.

I curse them going and I curse them riding; I curse them standing and I curse them sitting; I curse them eating and I curse them drinking; I curse them rising, and I curse them lying; I curse them at home, I curse them away from home; I curse them within the house, I curse them outside of the house; I curse their wives, their children, and their servants who participate in their deeds; their crops, their cattle, their wool, their sheep, their horses, their swine, their geese, their hens, and all their livestock; their halls, their chambers, their kitchens, their stanchions, their barns, their cowsheds, their barnyards, their cabbage patches, their plows, their harrows, and the goods and houses that are necessary for their sustenance and welfare.

May all the malevolent wishes and curses ever known, since the beginning of the world, to this hour, light on them. May the malediction of God, that fell upon Lucifer and all his fellows, that cast them from the high Heaven to the deep hell, light upon them.

May the fire and the sword that stopped Adam from the gates of Paradise, stop them from the glory of Heaven, until they forebear, and make amends.

May the evil that fell upon cursed Cain, when he slew his brother Abel, needlessly, fall on them for the needless slaughter that they commit daily.

May the malediction that fell upon all the world, man and beast, and all that ever took life, when all were drowned by the flood of Noah, except Noah and his ark, fall upon them and drown them, man and beast, and make this realm free of them, for their wicked sins.

May the thunder and lightning which rained down upon Sodom and Gomorrah and all the lands surrounding them, and burned them for their vile sins, rain down upon them and burn them for their open sins.

May the evil and confusion that fell on the Gigantis for their opression and pride in building the Tower of Babylon, confound them and all their works, for their open callous disregard and oppression.

May all the plagues that fell upon Pharaoh and his people of Egypt, their lands, crops and cattle, fall upon them, their equipment, their places, their lands, their crops and livestock.

May the waters of the Tweed and other waters which they use, drown them, as the Red Sea drowned King Pharaoh and the people of Egypt, preserving God’s people of Israel.

May the earth open, split and cleave, and swallow them straight to hell, as it swallowed cursed Dathan and Abiron, who disobeyed Moses and the command of God.

May the wild fire that reduced Thore and his followers to two-hundred-fifty in number, and others from 14,000 to 7,000 at anys, usurping against Moses and Aaron, servants of God, suddenly burn and consume them daily, for opposing the commands of God and Holy Church.

May the malediction that suddenly fell upon fair Absalom, riding through the wood against his father, King David, when the branches of a tree knocked him from his horse and hanged him by the hair, fall upon these untrue Scotsmen and hang them the same way, that all the world may see.

May the malediction that fell upon Nebuchadnezzar’s lieutenant, Holofernes, making war and savagery upon true Christian men; the malediction that fell upon Judas, Pilate, Herod, and the Jews that crucified Our Lord; and all the plagues and troubles that fell on the city of Jerusalem therefore, and upon Simon Magus for his treachery, bloody Nero, Ditius Magcensius, Olibrius, Julianus Apostita and the rest of the cruel tyrants who slew and murdered Christ’s holy servants, fall upon them for their cruel tyranny and murder of Christian people.

And may all the vengeance that ever was taken since the world began, for open sins, and all the plagues and pestilence that ever fell on man or beast, fall on them for their openly evil ways, senseless slaughter and shedding of innocent blood.

I sever and part them from the church of God, and deliver them immediately to the devil of hell, as the Apostle Paul delivered Corinth.

I bar the entrance of all places they come to, for divine service and ministration of the sacraments of holy church, except the sacrament of infant baptism, only; and I forbid all churchmen to hear their confession or to absolve them of their sins, until they are first humbled by this curse.

I forbid all Christian men or women to have any company with them, eating, drinking, speaking, praying, lying, going, standing, or in any other deed-doing, under the pain of deadly sin.

I discharge all bonds, acts, contracts, oaths, made to them by any persons, out of loyalty, kindness, or personal duty, so long as they sustain this cursing, by which no man will be bound to them, and this will be binding on all men.

I take from them, and cast down all the good deeds that ever they did, or shall do, until they rise from this cursing.

I declare them excluded from all matins, masses, evening prayers, funerals or other prayers, on book or bead; of all pigrimages and alms deeds done, or to be done in holy church or be Christian people, while this curse is in effect.

And, finally, I condemn them perpetually to the deep pit of hell, there to remain with Lucifer and all his fellows, and their bodies to the gallows of Burrow moor, first to be hanged, then ripped and torn by dogs, swine, and other wild beasts, abominable to all the world.

And their candle goes from your sight, as may their souls go from the face of God, and their good reputation from the world, until they forebear their open sins, aforesaid, and rise from this terrible cursing and make satisfaction and penance.

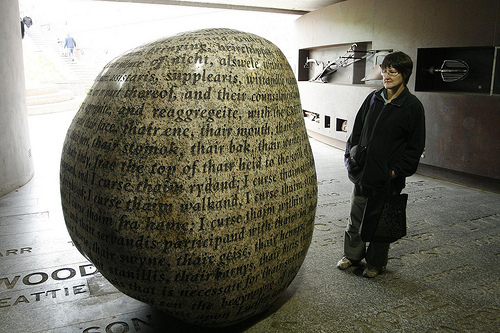

As part of Carlisle’s millennium celebrations in 2001, local artist Gordon Young carved 383 words of the curse into a granite boulder. Since then, local livestock herds have been wiped out by foot-and-mouth disease, a devastating flood has struck the city, factories have closed, and the Carlisle United soccer team dropped a league. Jim Tootle, a local councillor who blamed these misfortunes on the revived curse, himself died suddenly in 2011.

“It is a powerful work of art but it is certainly not part of the occult,” Young insisted. “If I thought my sculpture would have affected one Carlisle United result, I would have smashed it myself years ago.”