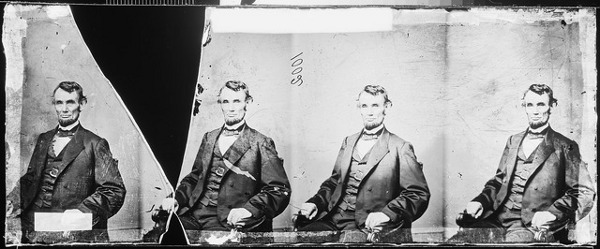

In 1908, while traveling in the northern Caucasus, Leo Tolstoy regaled a local tribe with tales of the greatest warriors and statesmen in history. When he had finished, the chief said, “But you have not told us a syllable about the greatest general and greatest ruler of the world. We want to know something about him. He was a hero. He spoke with a voice of thunder; he laughed like the sunrise, and his deeds were strong as the rock and as sweet as the fragrance of roses. The angels appeared to his mother and predicted that the son whom she would conceive would become the greatest the stars had ever seen. He was so great that he even forgave the crimes of his greatest enemies and shook brotherly hands with those who had plotted against his life. His name was Lincoln and the country in which he lived is called America, which is so far away that if a youth should journey to reach it he would be an old man when he arrived. Tell us of that man.”

“I looked at them,” Tolstoy recalled, “and saw their faces all aglow, while their eyes were burning. I saw that those rude barbarians were really interested in a man whose name and deeds had already become a legend.”

Tolstoy reflected that this “little incident proves how largely the name of Lincoln is worshipped throughout the world and how legendary his personality has become. Now, why was Lincoln so great that he overshadows all other national heroes? … [H]is supremacy expresses itself altogether in his peculiar moral power and in the greatness of his character. He had come through many hardships and much experience to the realization that the greatest human achievement is love. He was what Beethoven was in music, Dante in poetry, Raphael in painting, and Christ in the philosophy of life. He aspired to be divine — and he was. It is natural that before he reached his goal he had to walk the highway of mistakes. But we find him, nevertheless, in every tendency true to one main motive, and that was to benefit mankind. He was one who wanted to be great through his smallness. If he had failed to become President he would be, no doubt, just as great as he is now, but only God would appreciate it. The judgment of the world is usually wrong in the beginning, and it takes centuries to correct it. But in the case of Lincoln the world was right from the start.”