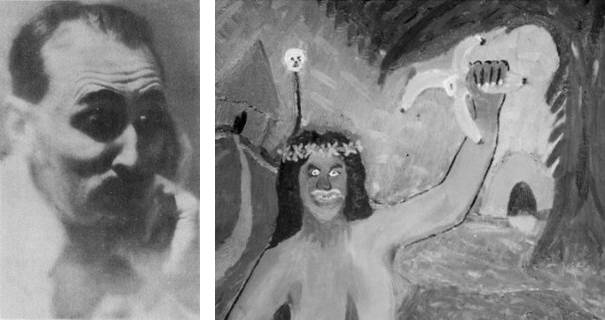

In 1924, irritated with the undiscerning faddishness of modern art criticism, Los Angeles novelist Paul Jordan Smith “made up my mind that critics would praise anything unintelligible.”

So he assembled some old paint, a worn brush, and a defective canvas and “in a few minutes splashed out the crude outlines of an asymmetrical savage holding up what was intended to be a star fish, but turned out a banana.” Then he slicked back his hair, styled himself Pavel Jerdanowitch, and submitted Exaltation to a New York artist group, claiming a new school called Disumbrationism.

The critics loved it. “Jerdanowitch” showed the painting at the Waldorf Astoria gallery, and over the next two years he turned out increasingly outlandish paintings, which were written up in Paris art journals and exhibited in Chicago and Buffalo.

He finally confessed the hoax to the Los Angeles Times in 1927. Ironically, “Many of the critics in America contended that since I was already a writer and knew something about organization, I had artistic ability, but was either too ignorant or too stubborn to see it and acknowledge it.” Can an artist found a school against his will?