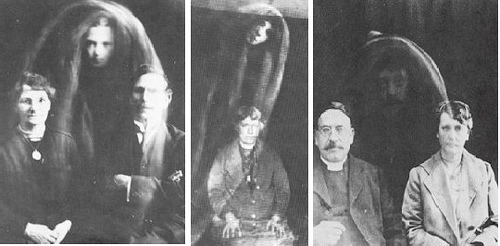

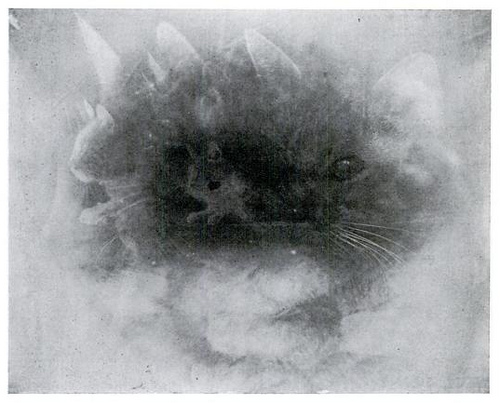

David Starr Jordan announced an exciting breakthrough in Popular Science Monthly in 1896: He’d asked seven people to think of a cat and then used a special device to capture their mental images and combine them into a composite picture, “the impression of ultimate feline reality.”

Jordan had intended the piece as a “gentle satire” of then-prevalent experiments in mental photography, but to his horror the readers took it seriously:

One clergyman even went so far as to announce a series of six discourses on “the Lesson of the Sympsychograph,” while many others welcomed the alleged discovery as verifying what they had long believed, and an eminent professor soberly opined that my reputation as a psychologist would not be enhanced by such discoveries!

He later wrote that the experience had taught him two lessons: “first, that very few people ever read a sensational article through to the end, even much beyond pictures and headlines, and second, that with Dr. Holmes, I should never again ‘dare to write as funny as I can.’”