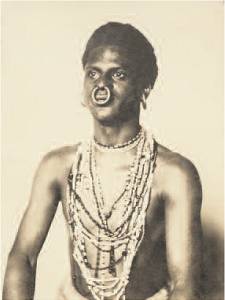

Bata Kindai Amgoza ibn LoBagola told an inspiring story: Born in West Africa, he wandered to the sea at age 7 and found himself aboard a steamer bound for Scotland. From there he made his way to the United States, where he took up lecturing. His 1930 autobiography, LoBagola; An African Savage’s Own Story, gives vivid details about life in the bush:

“If you should climb a tree, the lion can easily get help from the elephant, because the elephant and the lion are friendly. … [T]he lion tells the elephant that it wants you down from the tree, and the elephant shakes the tree or pulls it up by the roots, and down you come.”

The truth was more prosaic: His real name was Joseph Lee and he was born in Baltimore. “Small opportunities,” wrote Demosthenes, “are often the beginning of great enterprises.”