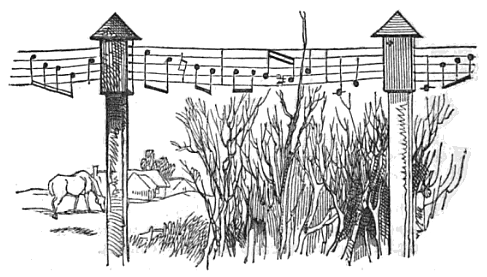

As telegraph lines began to appear along London’s railroads, they came to fascinate commuters. One wrote to the Illustrated London News to suggest that cornet lessons might now be given on the moving train.

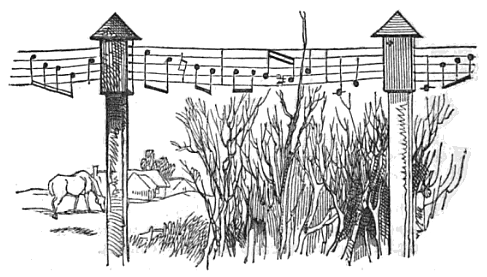

“The medium of tuition will be the wires of the electric telegraph. On these, being five, notes will be fastened by non-conducting materials, and the pupils will play them as they travel. The andante movements will be placed close to the stations, where progress is slow, and the tunes will be so arranged as to finish at all the stoppages. These will be constantly changed, to extend the benefit to all classes: for instance, galoppes will be chosen for the express trains; sets of quadrilles for the stopping ones; and marches, or dirges, for the luggage trains. At the same time, the passengers, generally, will be diverted with agreeable harmony.”

Another commuter responded: “The great objection is, that the notes once passed could never be taken up again, and especially the high ones; for, before the pupil could get his lips to the necessary embouchure, he would be a mile beyond the bar. A non-musical friend, given to senseless ribaldry, suggests that fugues should be chosen for the music; because, as he says, those compositions never appear to have beginning, end, middle, or anything else, and may be commenced or left of anywhere with equal effect.”

He adds, “It would be better, sir, for you to confine yourself to practical improvements than ingenious but futile schemes. … After my entertainments given in the country, I am usually asked to supper by certain of the leading inhabitants, in gratitude for the amusement I have afforded them; and, from drinking healths, I rise next morning with a dizziness. And then, on my return to town, are the wires of the electric telegraph most dreadful. They go up and down, down and up, for miles and miles, until at last, seeing nothing else, I begin to think that they are stationary, and it is the carriage which is undulating; and this has such an effect, that I am as indisposed upon arriving at the terminus as if I had just crossed the Channel. A little care on the part of the directors can remedy this. Why cannot the wires be turned upright, like those of a piano?”