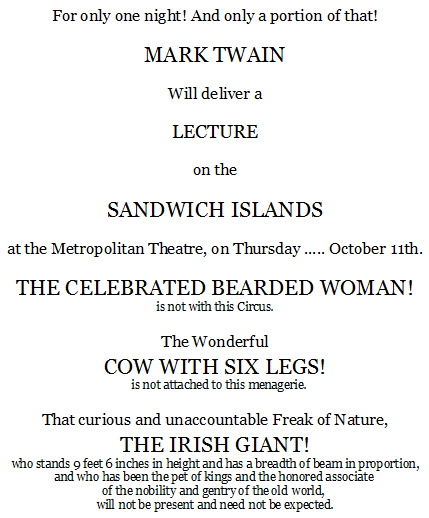

In 1866 Mark Twain embarked on a lecture tour in California. He wrote the handbills himself:

In Nevada City, he proposed to perform the following “wonderful feats of sleight of hand” after the lecture:

At a given signal, he will go out with any gentleman and take a drink. If desired, he will repeat this unique and interesting feat — repeat it until the audience are satisfied that there is no more deception about it.

At a moment’s warning, he will depart out of town and leave his hotel bill unsettled. He has performed this ludicrous feat many hundreds of times, in San Francisco, and elsewhere, and it has always elicited the most enthusiastic comments.

“The lecturer declines to specify any more of his miraculous feats at present,” he wrote, “for fear of getting the police too much interested in his circus.”