- Holmes and Watson never address one another by their first names.

- Until 1990, the banknote factory at Debden, England, was heated by burning old banknotes.

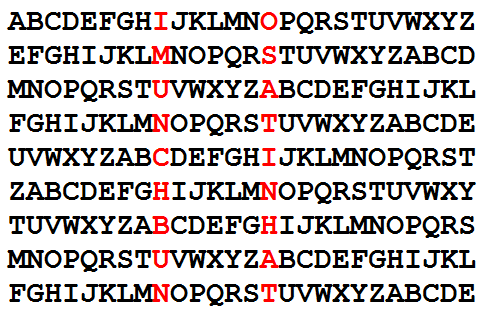

- The vowels AEIOUY can be arranged to spell the synonyms AYE and OUI.

- 741602 + 437762 = 7416043776

- “In all matters of opinion our adversaries are insane.” — Mark Twain

Two trick questions:

Who played the title role in Bride of Frankenstein? Valerie Hobson — not Elsa Lanchester.

Did Adlai Stevenson ever win national office? Yes — Adlai Stevenson I served as vice president under Grover Cleveland in 1893.