cark

v. to worry

kedogenous

adj. produced by worry

Some of your hurts you have cured

And the sharpest you still have survived,

But what torments of grief you endured

From evils which never arrived!

— Emerson

cark

v. to worry

kedogenous

adj. produced by worry

Some of your hurts you have cured

And the sharpest you still have survived,

But what torments of grief you endured

From evils which never arrived!

— Emerson

bubulcitate

v. to cry like a cowboy

(That’s from Henry Cockeram’s English Dictionary of 1623, so it doesn’t refer to a cowboy of the American West. What it does refer to is unclear. Cockeram said he included “even the mocke-words which are ridiculously used in our language,” but this word appears never to have been published outside of his dictionary, so we don’t know what a “cowboy” is or why he might cry. Make up your own meaning.)

AMERICAN is an anagram of CINERAMA.

MEXICAN is an anagram of CINEMAX.

lachschlaganfall

n. a condition in which a person falls unconscious due to violent laughter

USHERS contains five pronouns: HE, HER, HERS, SHE, US.

If rearranging letters is permitted, then SMITHERY contains 17: HE, HER, HERS, HIM, HIS, I, IT, ITS, ME, MY, SHE, THEIR, THEIRS, THEM, THEY, THY, YE.

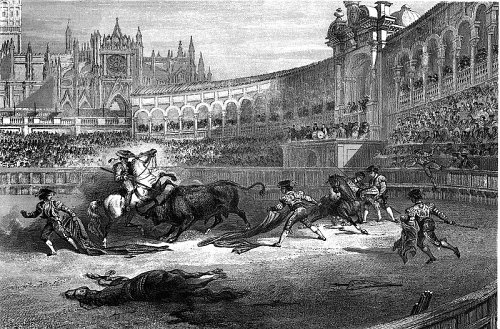

tauromachy

n. the art of bullfighting

Actress Alice Jeanne Leppert could have chosen any stage name she liked, but she decided on Alice Faye.

She didn’t notice that this is Pig Latin for phallus.

Brad Pitt’s daughter is named Shiloh … which yields an unfortunate spoonerism.

See Double Feature.

In his Night Thoughts (1953), Edmund Wilson lists these “anagrams on eminent authors”:

A! TIS SOME STALE THORN.

I ACHE RICH BALLADS, M!

I’M STAGY WHEN NEER.

LIVE MERMAN: HELL.

AWFUL KILLIN’, ERMA!

MAKZ ‘N NICE COMPOTE.

He gives no solutions. How many can you identify?

08/23/2023 UPDATE: Reader Jonathan Golding worked out the answers:

THOMAS STEARNS ELIOT

ARCHIBALD MACLEISH

ERNEST HEMINGWAY

HERMAN MELVILLE

WILLIAM FAULKNER

COMPTON MACKENZIE

Thanks, Jonathan!

nullibiety

n. the state of being nowhere

A contronym is a word with two contrary meanings, such as cleave or sanction (more here).

The word contronym itself has no double meaning. Is it a contronym?

“Not until I came along!” writes Charles Melton in Word Ways. “I declare that it is a contronym for the simple reason that it isn’t! It is both a self-opposite and not a self-opposite. QED.”