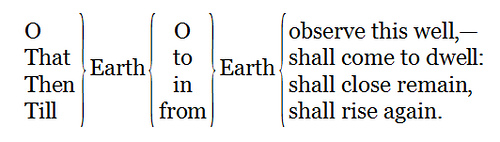

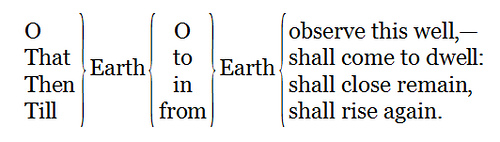

Epitaph in the churchyard of Llangerrig, Montgomeryshire:

— Charles Bombaugh, Facts and Fancies for the Curious From the Harvest-Fields of Literature, 1860

Epitaph in the churchyard of Llangerrig, Montgomeryshire:

— Charles Bombaugh, Facts and Fancies for the Curious From the Harvest-Fields of Literature, 1860

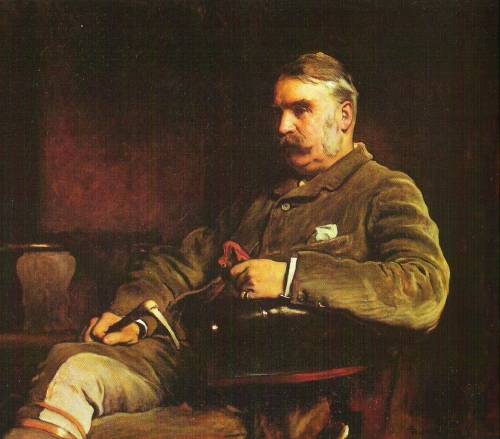

A whimsical letter written by W. S. Gilbert notes ‘a great want’ among poets. ‘I should like to suggest,’ he says, ‘that any inventor who is in need of a name for his invention, would confer a boon on the rhymsters, and at the same time insure himself many gratuitous advertisements, if he would select a word that rhymes to one of the many words in common use, which have but few rhymes or none at all. A few more words rhyming with ‘love’ are greatly wanted; ‘revenge’ and ‘avenge’ have no rhyming word, except ‘Penge’ and ‘Stonehenge’; ‘coif’ has no rhyme at all; ‘starve’ has no rhyme except (oh, irony!) ‘carve’; ‘scarf’ has no rhyme, though I fully expect to be told that ‘laugh,’ ‘calf,’ and ‘half’ are admissible, which they certainly are not.’

— Miscellaneous Notes and Queries, March 1894

“Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star” “revised by a committee of eminent preceptors and scholars”:

Shine with irregular, intermitted light, sparkle at intervals, diminutive, luminous, heavenly body.

How I conjecture, with surprise, not unmixed with uncertainty, what you are,

Located, apparently, at such a remote distance from, and at a height so vastly superior to this earth, the planet we inhabit,

Similar in general appearance and refractory powers to the precious primitive octahedron crystal of pure carbon, set in the aerial region surrounding the earth.

— William T. Dobson, Poetical Ingenuities and Eccentricities, 1882

eccedentesiast

n. one who fakes a smile

Here is the longest correct sentence of ‘thats’ which we have yet seen:

‘I assert that that, that that “that,” that that that that person told me contained, implied, has been misunderstood.’

It is a string of nine ‘thats’ which may be easily ‘parsed’ by a bright pupil.

— Boston Journal of Education, cited in Bizarre Notes & Queries, November 1887

“When young Sten was bar-mitzvahed, Sten Sr. took him on safari, as a present, during the course of which Mrs. Sten received this jubilant telegram”:

YOUNG STEN NETS GNU! OY!

— John McClellan

George Selwyn once declared in company that a lady could not write a letter without adding a postscript. A lady present replied, ‘The next letter that you receive from me, Mr. Selwyn, will prove that you are wrong.’ Accordingly he received one from her the next day, in which, after her signature was the following:–

‘P.S. Who is right, now, you or I?’

— Charles Carroll Bombaugh, Gleanings for the Curious from the Harvest-Fields of Literature, 1890

adoxography

n. fine writing on a trivial subject

With tragic air the love-lorn heir

Once chased the chaste Louise;

She quickly guessed her guest was there

To please her with his pleas.

Now at her side he kneeling sighed,

His sighs of woeful size;

‘Oh, hear me here, for lo, most low

I rise before your eyes.

This soul is sole thine own, Louise —

‘Twill never wean, I ween,

The love that I for aye shall feel,

Though mean may be its mien!’

‘You know I cannot tell you no,’

The maid made answer true;

I love you aught, as sure I ought —

To you ’tis due I do!’

‘Since you are won, Oh fairest one,

The marriage rite is right —

The chapel aisle I’ll lead you up

This night,’ exclaimed the knight.

— Yonkers Gazette, cited in William T. Dobson, Poetical Ingenuities and Eccentricities, 1882

fysigunkus

n. one who lacks curiosity