In 1970 Dirk Robson offered Krek Waiter’s Peak Bristle, a pronouncing dictionary for visitors to England’s West Country:

Armchair: Question meaning “What do they cost?” As in: “Armchair yer eat napples, mister?”

Claps: Fall to pieces.

Door: Female child.

Hard tack: Cardiac failure.

Justice Swell: Expression of right and proper behaviour; as in: “No, we dingo way, we stay dome. Justice swell — trained all week.”

Rifle: Deserving.

Sill Sernt: Government employee.

Sunny’s Cool: Bible class for the young.

Yerp: The Continent.

Examples from the field:

News vendor: “Snow end twit! Miniature rout of yes-dees news, yore rupture rise into daze!”

Patron: “Sway lie fizz, knit?”

And:

Woman at bus stop: “Fortify mince we bin stand near! Chews 2B bad, butts pasta joke now.”

Her companion: “Feud Dunce eye sedden walk tome, weed bin thereby now.”

Robson put out a companion volume, Son of Bristle, the following year, “with a special section on the famous Bristle ‘L.'” I’ll see if I can find that.

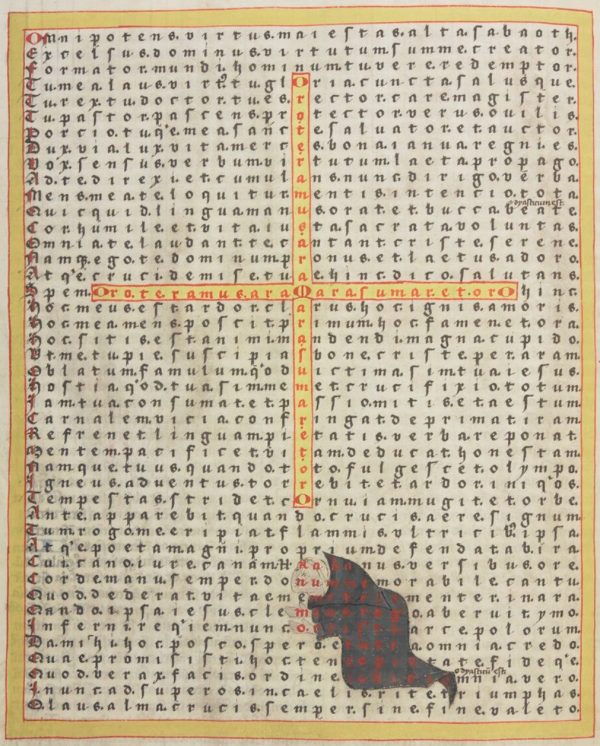

09/09/2023 UPDATE: Here’s the Bristol L:

(Thanks, Rob.)