This is just pleasing somehow: The Japanese railway station with the shortest name is Tsu Station in Mie Prefecture.

The name is written with a single stroke.

This is just pleasing somehow: The Japanese railway station with the shortest name is Tsu Station in Mie Prefecture.

The name is written with a single stroke.

compatchment

n. a thing patched together

emulous

adj. seeking to emulate

concinnity

n. harmony in the arrangement of parts with respect to a whole

featly

adv. neatly

In the autumn of 1947, Oxford mathematician John Henry Whitehead became fascinated with palindromes. He came up with STEP ON NO PETS but felt this could be surpassed. He put the problem to research student Peter Hilton, who suggested SEX AT NOON TAXES. Whitehead liked this but still felt that a longer sensible palindrome must be possible.

So Hilton spent an entire night working on the problem, writing nothing down, just lying in the dark. By morning he had:

DOC, NOTE, I DISSENT. A FAST NEVER PREVENTS A FATNESS. I DIET ON COD.

“Henry was delighted, and spread the word about my palindrome far and wide,” Hilton wrote later. Among those who heard about it were their former colleagues at Bletchley Park, where Whitehead and Hilton had helped to decrypt German ciphers during the war, and from there Hilton’s composition found its way into The Codebreakers, F.H. Hinsley and Alan Stripp’s account of that effort.

Robert Harris quoted the palindrome in his review of that book, “to indicate what sort of people the codebreakers were,” Hilton wrote. “But he also quoted the remark, attributed to Churchill, on the priority to be given to recruiting suitable people for this work: ‘When I told them to leave no stone unturned, I did not intend to be taken so literally.'”

(“Miscellanea,” College Mathematics Journal 30:5 [November 1999], 422-424.)

Roald Dahl wrote the film adaptations for two of Ian Fleming’s novels, You Only Live Twice and Chitty-Chitty-Bang-Bang.

(Thanks, Ben and Fred.)

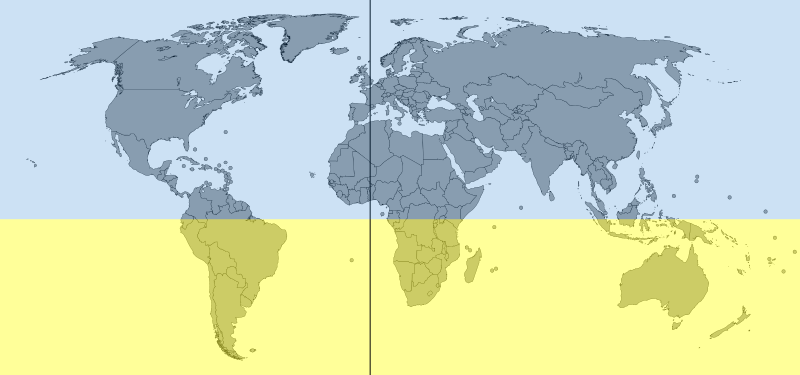

amphiscians

n. inhabitants of the tropics

angustation

n. the condition of being narrowed, constricted, limited, or confined

caducity

n. frailty, transitoriness

avolation

n. the act of flying away

This is the song of the last male Kauaʻi ʻōʻō, recorded in the Alaka’i Wilderness Preserve on Kauaʻi in 1987. Rats, pigs, hurricanes, and disease-carrying mosquitoes had reduced the species to a single pair by 1981, and the female was not found after Hurricane Iwa in 1982. The male was last seen in 1985. This appears to be his song, overheard two years later, the last trace of a vanishing species.

In 1922, Baltic German teacher and linguist Edgar de Wahl offered a new language to facilitate communication between people from different nations. He called it Occidental, and designed it so that many of its words will be recognizable by those who already know a Romance language:

Li material civilisation, li scientie, e mem li arte unifica se plu e plu. Li cultivat europano senti se quasi in hem in omni landes queles have europan civilisation, it es, plu e plu, in li tot munde. Hodie presc omni states guerrea per li sam armes. Sin cessa li medies de intercomunication ameliora se, e in consequentie de to li terra sembla diminuer se. Un Parisano es nu plu proxim a un angleso o a un germano quam il esset ante cent annus a un paisano frances.

“Material civilization, science, and even art unify themselves more and more. The educated European feels himself almost at home in all lands that have European civilization, that is, more and more, in the entire world. Today almost all states war with the same armaments. Without pause the modes of intercommunication improve, and in consequence from that the world seems to decrease. A Parisian is now closer to an Englishman or a German than he was a hundred years before to a French peasant.”

It gained a small community of speakers in the 1920s and 1930s and had largely died out by the 1980s — but in recent years it’s seen a resurgence on the Internet as Interlingue.

In the August 1841 issue of Graham’s Magazine, Edgar Allan Poe published a cryptogram composed by a Doctor Frailey of Washington and offered a year’s subscription to any reader who could solve it. In October he published the solution, which he’d managed to find:

In one of those peripatetic circumrotations I obviated a rustic whom I subjected to catechetical interrogation respecting the nosocomical characteristics of the edifice to which I was approximate. With a volubility uncongealed by the frigorific powers of villatic bashfulness, he ejaculated a voluminous replication from the universal tenor of whose contents I deduce the subsequent amalgamation of heterogeneous facts. Without dubiety incipient pretension is apt to terminate in final vulgarity, as parturient mountains have been fabulated to produce muscupular abortions. The institution the subject of my remarks, has not been without cause the theme of the ephemeral columns of quotidian journalism, and enthusiastic encomiations in conversational intercourse.

He was upbraided in November by a Richard Bolton of Pontotoc, Mississippi, who’d sent in a solution but received no credit. Poe redressed the error and added, “Your solution astonished me. You will accuse me of vanity in so saying — but truth is truth. I make no question that it even astonished yourself — and well it might – for from at least 100,000 readers — a great number of whom, to my certain knowledge, busied themselves in the investigation — you and I are the only ones who have succeeded.”

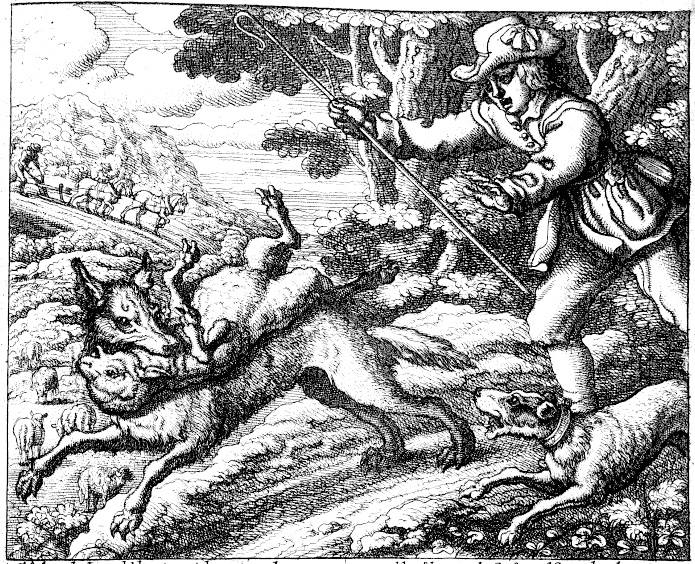

A boy, who kept watch on a flock of sheep, was heard from time to time to call out, ‘The Wolf! The Wolf!’ in mere sport. Scores of times, in this way, had he drawn the men in the fields from their work. But when they found it was a joke, they made up their minds that, should the boy call ‘Wolf’ once more, they would not stir to help him. The wolf, at last, did come. ‘The Wolf! The Wolf!’ shrieks out the boy, in great fear, but none will now heed his cries, and the wolf kills the boy, that he may feast on the sheep.

One knows not how to trust those who speak lies, though they may tell one the truth.

— From Lucy Aikin, Æsop’s Fables in Words of One Syllable, 1868

hortulan

adj. of or belonging to a garden

micacious

adj. sparkling, shining

bumfuzzle

v. to astound or bewilder

asomatous

adj. having no material body

Artist Gary Drostle designed this trompe l’oeil mosaic for a public garden in Croydon in 1996.

He calls it “the ideal low maintenance fishpond.”

We Fada wa dey een heaben,

leh ebreybody hona ya name.

We pray dat soon ya gwine

rule oba de wol.

Wasoneba ting ya wahn,

leh um be so een dis wol

same like dey een heaben.

Gii we de food wa we need

dis day yah en ebry day.

Fagib we fa we sin,

same like we da fagib

dem people wa do bad ta we.

Leh we dohn hab haad test

wen Satan try we.

Keep we fom ebil.

From the New Testament in Gullah. The whole book is here.