viator

n. a wayfarer; traveler

nocuous

adj. likely to cause harm or damage

fulminant

adj. exploding or detonating

aggerose

adj. in heaps

British director Cecil Hepworth made “How It Feels To Be Run Over” in 1900. The car is on the wrong side of the road. (The intertitle at the end, “Oh! Mother will be pleased,” may have been scratched directly into the celluloid.)

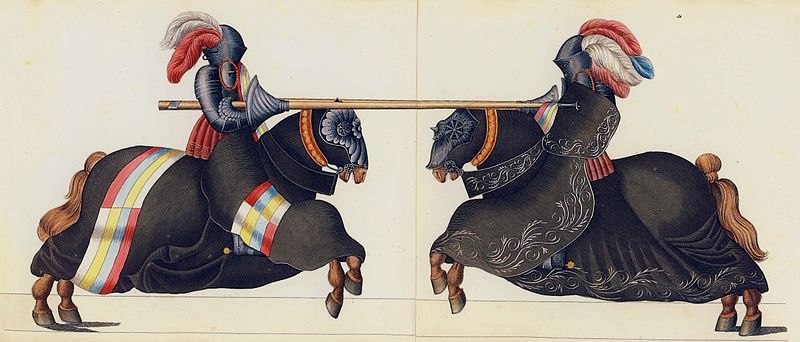

Hepworth followed it up with “Explosion of a Motor Car,” below, later the same year.