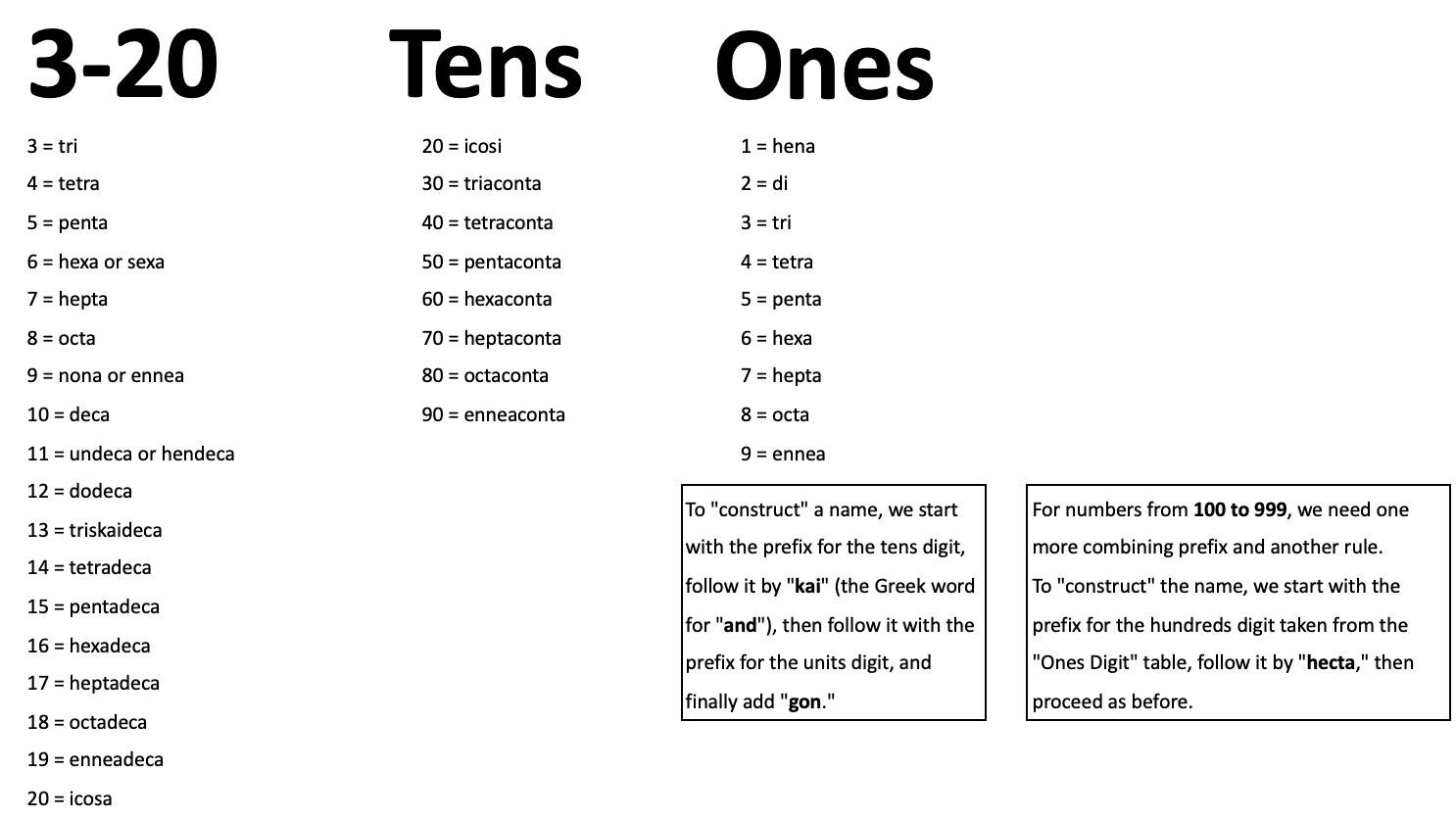

In a 1954 essay, “The English Aristocracy,” Nancy Mitford observed that English class consciousness had permeated the language itself, so that using the wrong term betrayed a lack of breeding. She had been inspired by linguist Alan S.C. Ross, who distinguished upper-class (“U”) terms from those used by the middle class:

|

U

|

Non-U

|

|

Bike or Bicycle

|

Cycle

|

|

Dinner jacket

|

Dress suit

|

|

Knave (cards) |

Jack

|

|

Vegetables |

Greens

|

|

Ice

|

Ice cream

|

|

Scent

|

Perfume

|

|

They’ve a very nice house

|

They have (got) a lovely home

|

|

Ill (in bed)

|

Sick (in bed)

|

|

Looking-glass

|

Mirror

|

|

Chimneypiece

|

Mantelpiece

|

|

Graveyard

|

Cemetery

|

|

Spectacles

|

Glasses

|

|

False teeth

|

Dentures

|

|

Die

|

Pass on

|

|

Mad

|

Mental

|

|

Jam

|

Preserve

|

|

Napkin

|

Serviette

|

|

Sofa

|

Settee or couch

|

|

Lavatory or loo

|

Toilet

|

|

Rich

|

Wealthy

|

|

Good health

|

Cheers

|

|

Lunch

|

Dinner (for midday meal)

|

|

Pudding

|

Sweet

|

|

Drawing-room

|

Lounge

|

|

Writing-paper

|

Note-paper

|

|

What?

|

Pardon?

|

|

How d’you do?

|

Pleased to meet you

|

|

Wireless

|

Radio

|

|

(School)master, mistress

|

Teacher

|

Ross added, “It is solely by their language that the upper classes nowadays are distinguished since they are neither cleaner, richer, nor better-educated than anybody else.” Mitford said she’d written the essay “In order to demonstrate the upper middle class does not merge imperceptibly into the middle class.”

The essay touched off a vigorous national debate about English snobbery; Mitford’s essay was published in a 1956 book, Noblesse Oblige, to which John Betjeman contributed a mordant poem, “How to Get On in Society”:

Phone for the fish knives, Norman

As cook is a little unnerved;

You kiddies have crumpled the serviettes

And I must have things daintily served.

Are the requisites all in the toilet?

The frills round the cutlets can wait

Till the girl has replenished the cruets

And switched on the logs in the grate.

It’s ever so close in the lounge dear,

But the vestibule’s comfy for tea

And Howard is riding on horseback

So do come and take some with me

Now here is a fork for your pastries

And do use the couch for your feet;

I know that I wanted to ask you-

Is trifle sufficient for sweet?

Milk and then just as it comes dear?

I’m afraid the preserve’s full of stones;

Beg pardon, I’m soiling the doileys

With afternoon tea-cakes and scones.

(Alan S.C. Ross, “Linguistic Class-Indicators in Present-Day English.” Neuphilologische Mitteilungen 55:1 [1954], 20-56.)