Guido Nazzo, an Italian tenor of the 1930s, sang only once in New York and received but one review: ‘Guido Nazzo: nazzo guido.’

— Willard R. Espy, Another Almanac of Words at Play, 1981

Guido Nazzo, an Italian tenor of the 1930s, sang only once in New York and received but one review: ‘Guido Nazzo: nazzo guido.’

— Willard R. Espy, Another Almanac of Words at Play, 1981

In 2017 research scientist Janelle Shane tried to train a neural network to name kittens:

Jeckle

Elbent

Jenderina

Roober

Snorp

Snox Boops

Cylon

Sookabear

Jexley Pickle

Toby Booch

Snowpie

Big Wiggy Bool

Mr Whinkles

Licky Cat

Mr Bincheh

Maxy Fay

Mr Gruffles

Liony Oli

Lingo

Conkie

Lasley Goo

Marvish

Mag Jeggles

Corko

Maggin

Mcguntton

Mara Tatters

Mush Jam

Tilly-Mapper

Mr. Jubble

Mumcake

Muppin

Bonus: At one point she accidentally trained the network on a dataset of character names from Tolkien, George R.R. Martin, and other fantasy authors and got Jarlag, Mankith, Andend of Karlans, and Mr. Yetheract. See the full list.

Now if mouse in the plural should be, and is, mice,

Then house in the plural, of course, should be hice,

And grouse should be grice and spouse should be spice

And by the same token should blouse become blice.

And consider the goose with its plural of geese;

Then a double caboose should be called a cabeese,

And noose should be neese and moose should be meese

And if mama’s papoose should be twins, it’s papeese.

Then if one thing is that, while some more is called those,

Then more than one hat, I assume, would be hose,

And gnat would be gnose and pat would be pose

And likewise the plural of rat would be rose.

— Author unknown

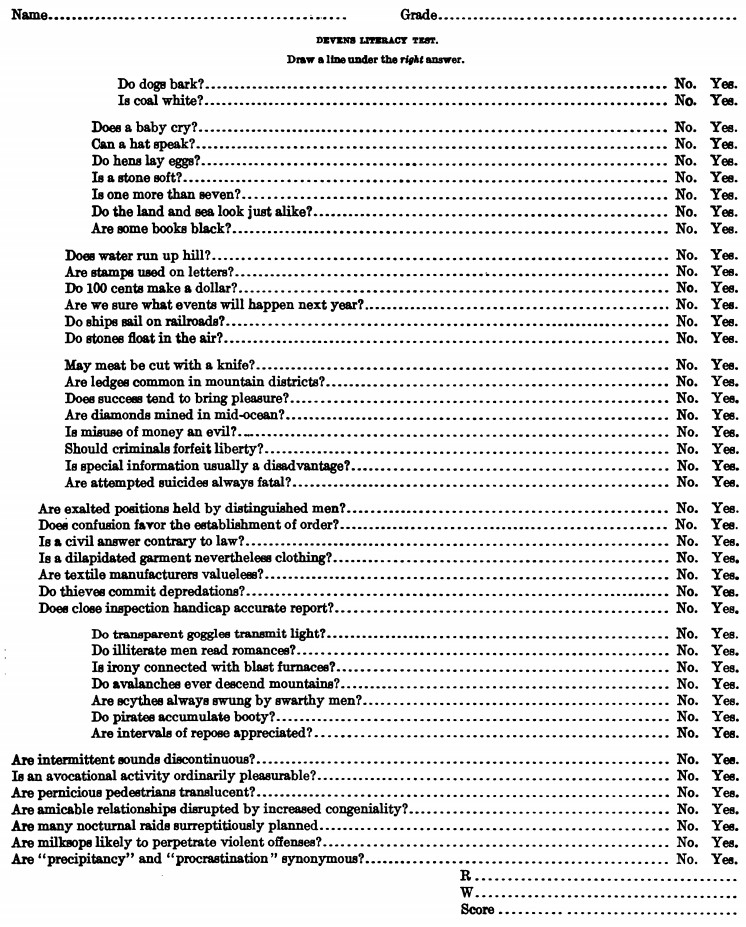

This test was administered to recruits at Fort Devens, Mass., during World War I. The idea is to measure reading comprehension, but the questions take on a surreal poetry:

Norms:

Below 6: Illiterate

6 to 20: Primary

21 to 25: Grammar

26 to 30: Junior high school

31 to 35: Senior high school

36 to 42: College

Three additional versions of the test are given here.

The French word for fanlight, vasistas, derives from the German phrase Was ist das? (“Who’s there?” or literally “What is that?”).

There seem to be two competing explanations: Either German visitors to France were unfamiliar with these windows and commonly asked about them — or French visitors to Germany often heard that phrase called through the window before the door opened.

(Thanks, Tony.)

“Animals seen as sport become to the mind meat, and cease to be individual creatures, so that you may feed fishes, but catch fish, ride elephants, but hunt elephant, fatten turkeys and pigs, but chase turkey and pig, throw bread to ducks, but shoot duck; and some creatures, whom God would seem to have created merely for the chase, such as grouse and snipe, require no plural forms at all. And even as few as two pigs become pig if hunted.” — Rose Macaulay

In Thomas Tryon’s Country-Man’s Companion (1684), the birds upbraid man, “O thou Two-Leg’d unfeather’d unthinking Thing,” for his slaughter:

How many thousands of our innocent kind have been murthered by Guns, Traps, Snares, &c? and many thousands both of our Males and Females have lost their loving Mates by the like Stratagems, and no Pity or Compassion taken by Man on our miserable Sufferings, but rather they encourage each other to our destruction, and cry, Hang these scurvey Birds, shoot them, destroy them, they are good for nothing but to eat up our Corn: As if God that created us had done it in vain, as if he intended us not a subsistance and Food? What right I pray, has Man to all the Corn in the world? or why should he grumble and repine if we take a few Grains to supply our Necessities, whilst he squanders away such Heaps upon his Lusts? Wherein I fear he has so much besotted himself, and by continual Practice is become so harden’d, and has so powerfully irritated the dark Wrath in himself, that all our Remonstrances to him to move him to Mercy and Compassion, and to forbear polluting himself with the Blood of the Innocent, will be but in vain, and that we must still sigh and groan under his Cruelty and Tyranny, which as long-run will return seven fold upon his own guilty Head.

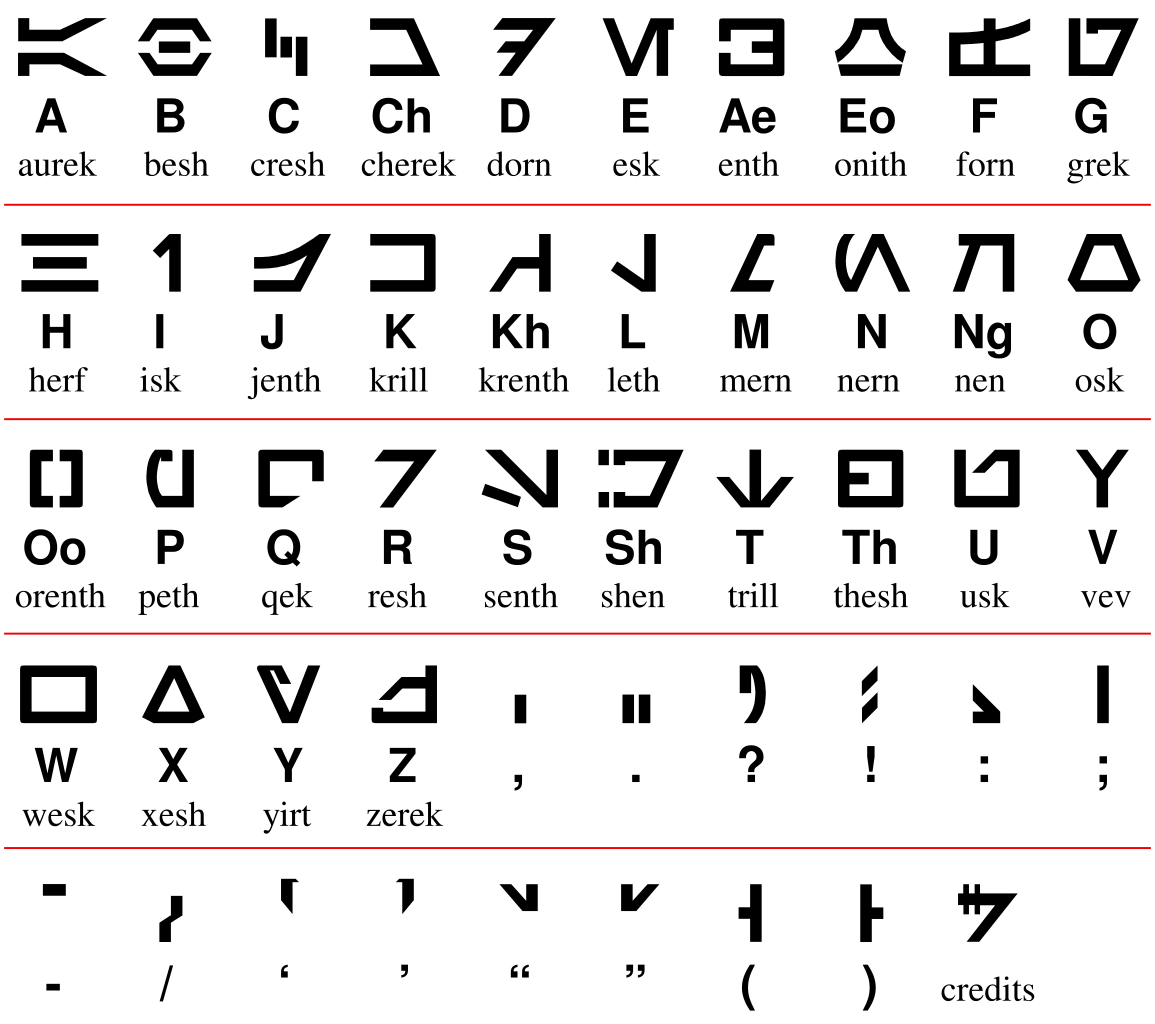

At the beginning of 1983’s Return of the Jedi, the third film in the original Star Wars trilogy, an alien script could be seen on monitor readouts on the second Death Star. Devised by artist Joe Johnston, these lines weren’t intended to be read, but West End Games art director Stephen Crane gave each character a name, creating an alphabet for gamers to use.

With Lucasfilm’s approval, this has become “Aurabesh,” a 34-letter writing system named for its first two letters, aurek and besh. And Aurabesh has now found its way into Star Wars films, books, comics, and TV series. Since the 2004 DVD release of A New Hope, the original film in the series, the words on the Death Star’s tractor beam control have appeared in Aurebesh, bringing the alphabet’s adoption full circle.

“The Aurebesh is a lot like Boba Fett,” Crane wrote. “It is a facet of the Star Wars phenomenon that had its origin as a cinematic aside, but which has come to be widely embraced, far out of proportion to its humble origins.”

allograph

n. something written for another person

facrere

n. the art of “make-believe”

dabster

n. a master of his business

gelastic

n. something capable of exciting smiles or laughter

Leroy Anderson’s 1950 composition “The Typewriter” uses a manual typewriter as an instrument.

To keep the keys from jamming, the machine is modified so that only two keys work. All the same, Anderson found that percussionists perform it more reliably than typists do.

“We have two drummers,” Anderson said in a 1970 interview. “A lot of people think we use stenographers, but they can’t do it because they can’t make their fingers move fast enough. So we have drummers because they can get wrist action.”

Jerry Lewis famously adopted the piece for his 1963 film Who’s Minding the Store?, below.

In Foucault’s Pendulum, Umberto Eco suggests a technique for making one language look like another:

Abu, do another thing now: Belbo orders Abu to change all words, make each ‘a’ become ‘akka’ and each ‘o’ become ‘ulla,’ for a paragraph to look almost Finnish.

Akkabu, dulla akkanullather thing nullaw: Belbulla ullarders Akkabu tulla chakkange akkall wullards, makkake eakkach ‘akka’ becullame ‘akkakkakka’ akkand eakkach ‘ulla’ becullame ‘ullakka,’ fullar akka pakkarakkagrakkaph tulla lullaullak akkalmulast Finnish.

In a 1955 letter to W.H. Auden, J.R.R. Tolkien described his discovery of the Finnish language: “It was like discovering a complete wine-filled cellar filled with bottles of an amazing wine of a kind and flavor never tasted before. It quite intoxicated me …”