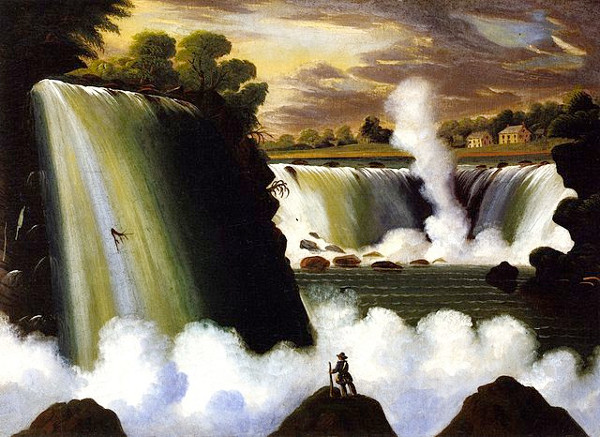

videnda

n. things worth seeing

videnda

n. things worth seeing

As military and computer technology exploded in the early 1960s, Raytheon compiled a helpful list of 400 “space-age” abbreviations:

CHAMPION — Compatible Hardware And Milestone Program for Integrating Organizational Needs

COED — Computer Operated Electronic Display

DASTARD — Destroyer Anti-Submarine Transportable ARray Detector

PIPER — Pulsed Intense Plasma for Exploratory Research

It published the list in a booklet titled ABbreviations and Related ACronyms Associated with Defense, Astronautics, Business, and RAdio-electronics — or ABRACADABRA for short.

bardocucullated

adj. wearing a cowled cloak

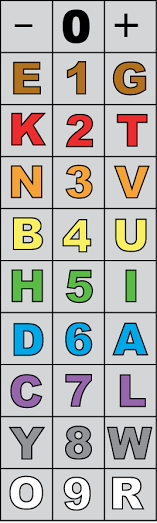

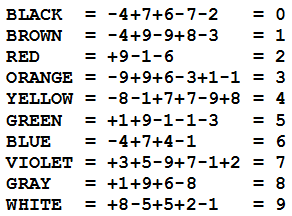

From Lee Sallows: The international color code is used to mark the values of electronic components such as resistors. It assigns a distinct color to each of the 10 decimal digits, as seen in the center column of the table at right: 0 = BLACK, 1 = BROWN, …, 9 = WHITE.

Lee’s table has an ingenious reflexive property. The letters in the left-hand column are associated with the values -1 to -9, and those in the right-hand column with the values 1 to 9.

Now spelling the name of each color produces a sum that matches the number represented by that color:

“This is more remarkable that it may seem,” Lee writes, “because the numbers assigned to the letters are now restricted to single-digit values only.”

In one oft-repeated anecdote from the memoirs of Melville Stone, publisher of the Chicago Daily News in the 1870s, the News suspected that the Chicago Post and Mail, published by the McMullen brothers, was pirating its stories. The News retaliated by printing an account of a famine in Serbia, in which the local mayor was quoted as saying (ostensibly in Serbian) ‘Er us siht la Etsll iws nel lum cmeht.’ When the afternoon edition of the Post and Mail duly reproduced the quote, Stone ran to all the other Chicago papers to reveal the hoax: read backward, the supposed quote said ‘The McMullens will steal this sure.’ According to Stone, the Post and Mail never recovered from the embarrassment, and the Daily News was able to buy it for a pittance less than two years later.

— Stuart Banner, American Property: A History of How, Why, and What We Own, 2011

(Thanks, Keith.)

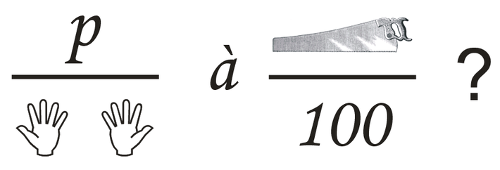

It’s said that when Frederick the Great hosted Voltaire at Sanssouci Palace, he sent him this puzzling note:

It’s a rebus in French: deux mains sous Pé à cent sous scie? (“two hands under ‘p’ at hundred under saw”) means demain souper à Sanssouci? (“supper tomorrow at Sanssouci?”).

Voltaire replied “Ga!”: Gé grand, A petit! (“big ‘G’, small ‘a’!”) means j’ai grand appétit!, or “I am very hungry!”

excogitous

adj. inventive

volitorial

adj. pertaining to flying

empyreuma

n. a burnt smell

Newsreel men recently witnessed an unscheduled drama as flames ended the attempt of Constantinos Vlachos, co-inventor of one of the strangest of flying craft, to win government aid for its development. He had planned an ascent from the lawn of the Congressional Library at Washington, D.C., to demonstrate his ‘triphibian,’ which he claimed could navigate in the air, on land, or in the water. Hardly had he started the motor when fire enveloped the machine. Spectators dashed to his aid and dragged him, severely burned, from the blazing wreck.

— Popular Science, January 1936

(Thanks, Tucker.)

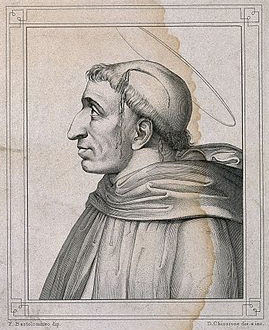

GIROLAMO SAVONAROLA alternates vowels and consonants.

(Thanks, Joseph.)

“To the memory of Miss Emily Kay, cousin to Miss Ellen Gee, of Kew, who died lately at Ewell, and was buried in Essex.”

Sad nymphs of U L, U have much to cry for,

Sweet M L E K U never more shall C!

O S X maids! come hither and D 0,

With tearful I, this M T L E G.

Without X S she did X L alway,

Ah me! it truly vexes 1 2 C

How soon so D R a creature may D K,

And only leave behind X U V E!

Whate’er 1 0 to do she did discharge,

So that an N M E it might N D R:

Then why an S A write? — then why N

Or with my briny tears B D U her B R?

When her Piano-40 she did press,

Such heavenly sounds did M N 8, that she

Knowing her Q, soon 1 U 2 confess

Her X L N C in an X T C.

Her hair was soft as silk, not Y R E,

It gave no Q, nor yet 2 P to view:

She was not handsome; shall I tell U Y?

U R 2 know her I was all S Q.

L 8 she was, and prattling like a J;

How little, M L E! did you 4 C,

The grave should soon M U R U, cold as clay,

And you shall cease to be an N T T!

While taking T at Q with L N G,

The M T grate she rose to put a :

Her clothes caught fire — no 1 again shall see

Poor M L E, who now is dead as Solon.

O L N G! in vain you set at 0

G R and reproach for suffering her 2 B

Thus sacrificed; to J L U should be brought,

Or burnt U 0 2 B in F E G.

Sweet M L E K into S X they bore,

Taking good care the monument 2 Y 10,

And as her tomb was much 2 low B 4,

They lately brought fresh bricks the walls to 10.

— Horace Smith, in A Budget of Humorous Poetry, 1866

(This is a bit more recondite than the Ellen Gee poem. “D 0” is decipher, “1 0 to” is one ought to, N is enlarge, 10 is heighten, and “X U V E,” I am pleased to understand, is exuviae, “an animal’s cast or sloughed skin.” Let’s hope it stopped here.)

Large as the English word-stock is, it is not perfect. There are a number of situations which other languages have a single word for, but which English must express by circumlocution. Some of these were described by Dmitri Borgmann in the February 1970 Word Ways. For example, the English phrase ONE AND ONE HALF is succinctly described by Polish POLTORA, German ANDERTHALB or Latin SESQUIALTER. (In fact the Polish even have the word POLOSMA for SEVEN AND ONE HALF!) Similarly, English THE DAY BEFORE YESTERDAY is more compactly expressed by German VORGESTERN or Spanish ANTEAYER, and English THE DAY AFTER TOMORROW by German UBERMORGEN, Italian DOPODOMANI or Polish POJUTRZE. To express relationships, German uses GESCHWISTER for BROTHERS AND SISTERS, Polish uses STRYJ for the paternal uncle and WUJ for the maternal uncle, and SZWAGROSTWO for one’s husband’s brother and his wife.

— A. Ross Eckler, “English: Best For(e)play With Words,” Word Ways, August 2008