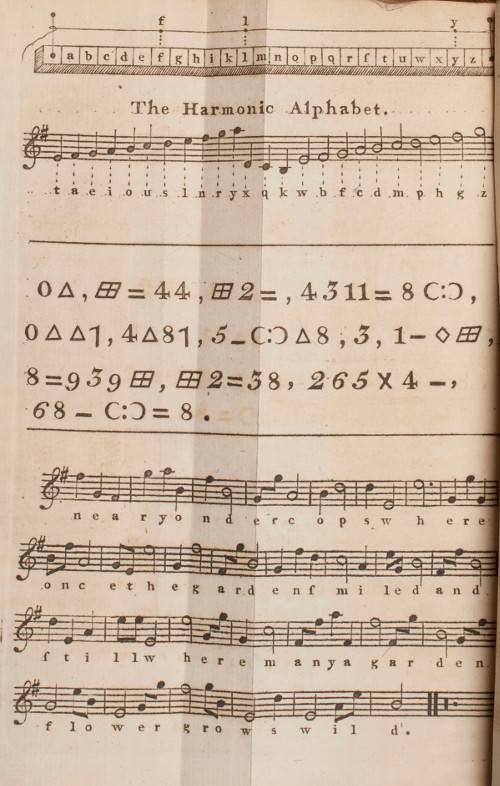

In his 1772 Treatise on the Art of Decyphering, Philip Thicknesse suggests a scheme for hiding messages in musical compositions:

At the bottom of the page is an example. “If a musick-master be required to play it, he will certainly think it an odd, as well as a very indifferent, composition; but neither he, or any other person, will suspect that the notes convey also the two following harmonious lines from Dr. Goldsmith’s poem The Deserted Village“:

Near yonder cops where once the garden smil’d,

And still where many a garden-flower grows wild.

Thicknesse suggests that two players might even use this scheme to carry on a conversation in real time. “It is certain that two musicians might, by a very little application, carry on a correspondence with their instruments: they are all in possession of the seven notes, which express a, b, c, d, e, f, g; and know by ear exactly, when either of those notes are toned; and they are only to settle a correspondence of tones, for the remaining part of the alphabet; and thus a little practice, might enable two fiddlers to carry on a correspondence, which would greatly astonish those who did not know how how the matter was conducted. Indeed this is no more than what is called dactlylogy, or talking on the fingers, which I have seen done, and understood as quick, and readily almost, as common conversation.”