I think this first appeared in the puzzle newsletter The Ag Mine — 12 chemical elements can be spelled using element symbols:

ArSeNiC

AsTaTiNe

BiSmUTh

CArBON

CoPPEr

IrON

KrYPtON

NeON

PHOsPHORuS

SiLiCoN

TiN

XeNoN

See Transmutation.

I think this first appeared in the puzzle newsletter The Ag Mine — 12 chemical elements can be spelled using element symbols:

ArSeNiC

AsTaTiNe

BiSmUTh

CArBON

CoPPEr

IrON

KrYPtON

NeON

PHOsPHORuS

SiLiCoN

TiN

XeNoN

See Transmutation.

carfax

n. a place where four roads meet

Traveling between country towns, you arrive at a lonely crossroads where some mischief-maker has uprooted the signpost and left it lying by the side of the road.

Without help, how can you choose the right road and continue your journey?

eriff

n. a two-year-old canary

plagose

adj. fond of flogging

baculine

adj. pertaining to punishment by flogging

mastigophorous

adj. carrying a whip

Pedro Carolino thought he was doing the world a favor in 1883 when he published English As She Is Spoke, ostensibly a Portuguese-English phrasebook. The trouble is that Carolino didn’t speak English — apparently he had taken an existing Portuguese-French phrasebook and mechanically translated the French to English using a dictionary, assuming that this would produce proper English. It didn’t:

It must to get in the corn.

He burns one’s self the brains.

He not tooks so near.

He make to weep the room.

I should eat a piece of some thing.

I took off him of perplexity.

I dead myself in envy to see her.

The sun glisten?

The thunderbolt is falling down.

Whole to agree one’s perfectly.

Yours parents does exist yet?

A dialogue with a bookseller:

What is there in new’s litterature?

Little or almost nothing, it not appears any thing of note.

And yet one imprint many deal.

That is true; but what it is imprinted. Some news papers, pamphlets, and others ephemiral pieces: here is.

But why, you and another book seller, you does not to imprint some good works?

There is a reason for that, it is that you canot to sell its. The actual-liking of the public is depraved they does not read who for to amuse one’s self ant but to instruct one’s.

But the letter’s men who cultivate the arts and the sciences they can’t to pass without the books.

A little learneds are happies enough for to may to satisfy their fancies on the literature.

An anecdote:

One eyed was laied against a man which had good eyes that he saw better than him. The party was accepted. “I had gain, over said the one eyed; why I see you two eyes, and you not look me who one.”

Proverbs:

The walls have hearsay.

Nothing some money, nothing of Swiss.

He has a good beak.

The dress don’t make the monk.

They shurt him the doar in the face.

Every where the stones are hards.

Burn the politeness.

To live in a small cleanness point.

To craunch the marmoset.

Mark Twain wrote, “In this world of uncertainties, there is, at any rate, one thing which may be pretty confidently set down as a certainty: and that is, that this celebrated little phrase-book will never die while the English language lasts. … Whatsoever is perfect in its kind, in literature, is imperishable: nobody can add to the absurdity of this book, nobody can imitate it successfully, nobody can hope to produce its fellow; it is perfect, it must and will stand alone: its immortality is secure.”

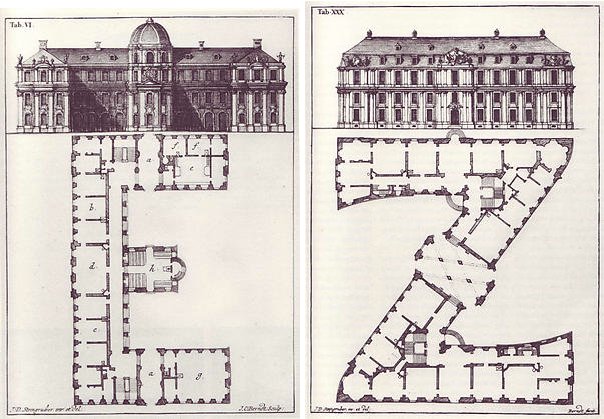

Johann David Steingruber fulfilled his literary ambitions on a drafting table — his Architectural Alphabet (1773) renders each letter of the alphabet as the floor plan of a palace.

Antonio Basoli’s Alfabeto Pittorico (1839) presents the letters as architectural drawings:

Perhaps next we can actually build them.

impervestigable

adj. incapable of being fully investigated

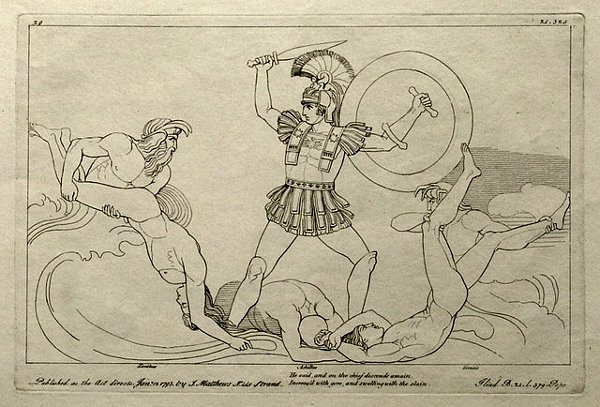

Achillize

v. to harass or chase in a manner reminiscent of Achilles

Brad Pitt, who played Achilles in the 2004 film Troy, tore his Achilles tendon during production.

It was British wordplay expert Leigh Mercer who coined the classic palindrome “A man, a plan, a canal — Panama” in Notes & Queries on Nov. 13, 1948. He later said that he’d had the middle portion, PLAN A CANAL P, for a year before he saw that PANAMA fit.

Mercer published 100 palindromes in N&Q between 1946 and 1953 — a selection:

See, slave, I demonstrate yet arts no medieval sees

Now Ned I am a maiden won

Here so long? No loser, eh?

Trade ye no mere moneyed art

Ban campus motto, “Bottoms up, MacNab”

No dot nor Ottawa “legal age” law at Toronto, Don

Now ere we nine were held idle here, we nine were won

Egad, a base life defiles a bad age

“Reviled did I live,” said I, “as evil I did deliver”

I saw desserts, I’d no lemons, alas, no melon, distressed was I

Sue, dice, do, to decide us

Sir, I demand — I am a maid named Iris

No, set a maple here, help a mate, son

Poor Dan is in a droop

Yawn a more Roman way

Won’t lovers revolt now?

Pull a bat, I hit a ball up

Nurse, I spy gypsies, run!

Stephen, my hat — ah, what a hymn, eh, pets?

Pull up if I pull up

… and the remarkably natural “Evil is a name of a foeman, as I live.”

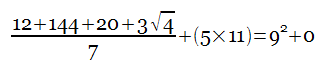

Mercer didn’t confine himself to palindromes — he also devised this mathematical limerick:

A dozen, a gross, and a score

Plus three times the square root of four

Divided by seven

Plus five times eleven

Is nine squared and not a bit more.