Maud was Tennyson’s own favorite poem, but critics were put off by its themes of death, loss, war, and murder.

One suggested that there were too many vowels in the title — and that either of them could go.

Maud was Tennyson’s own favorite poem, but critics were put off by its themes of death, loss, war, and murder.

One suggested that there were too many vowels in the title — and that either of them could go.

In 2007, prison inmate Charles Jay Wolff sent a hard-boiled egg to U.S. District Court Judge James Muirhead in Concord, N.H.

Wolff, who was awaiting trial for sexual assault, said he was an Orthodox Jew and demanded a kosher diet.

In his judgment, Muirhead wrote:

I do not like eggs in the file.

I do not like them in any style.

I will not take them fried or boiled.

I will not take them poached or broiled.

I will not take them soft or scrambled,

Despite an argument well-rambled.

No fan I am of the egg at hand.

Destroy that egg! Today! Today!

Today I say!

Without delay!

“We’ve told him, if you don’t like the eggs, don’t eat them,” said Assistant Attorney General Andrew Livernois.

In 1793, two years after publishing his translation of Homer, William Cowper received this letter from 12-year-old Thomas Hayley, pointing out its defects:

HONORED KING OF BARDS,–Since you deign to demand the observations of an humble and unexperienced servant of yours, on a work of one who is so much his superior (as he is ever ready to serve you with all his might) behold what you demand! but let me desire you not to censure me for my unskilful and perhaps (as they will undoubtedly appear to you) ridiculous observations; but be so kind as to receive them as a mark of respectful affection from your obedient servant,

THOMAS HAYLEY

Book I, Line 184. I cannot reconcile myself to these expressions, ‘Ah, cloth’d with impudence, etc.’; and 195, ‘Shameless wolf’; and 126, ‘Face of flint.’

Book I, Line 508. ‘Dishonor’d foul,’ is, in my opinion, an uncleanly expression.

Book I, Line 651. ‘Reel’d,’ I think makes it appear as if Olympus was drunk.

Book I, Line 749. ‘Kindler of the fires in Heaven,’ I think makes Jupiter appear too much like a lamplighter.

Book II, Lines 317-319. These lines are, in my opinion, below the elevated genius of Mr. Cowper.

Book XVIII, Lines 300-304. This appears to me to be rather Irish, since in line 300 you say, ‘No one sat,’ and in 304, ‘Polydamas rose.’

Cowper wrote back, “A fig for all critics but you!”

The Cat in the Hat uses 225 different words.

Dr. Seuss’ publisher, Bennett Cerf, wagered $50 that the author couldn’t reduce this total to 50 in his next book.

So Seuss produced a new manuscript using precisely 50 words, and collected the $50.

The book was Green Eggs and Ham.

Two months before the outbreak of World War I, Arthur Conan Doyle published a curious short story in The Strand. “Danger! Being the Log of Captain John Sirius” told of a fleet of enemy submarines attacking England’s food imports, starving the nation and winning a war:

Of course, England will not be caught napping in such a fashion again! Her foolish blindness is partly explained by her delusion that her enemy would not torpedo merchant vessels. Common sense should have told her that her enemy will play the game that suits them best — that they will not inquire what they may do, but they will do it first and talk about it afterwards.

In a commentary published with the story, Adm. Penrose Fitzgerald wrote, “I do not myself think that any civilized nation will torpedo unarmed and defenceless merchant ships.” Adm. Sir Compton Domvile felt “compelled to say that I think it most improbable, and more like one of Jules Verne’s stories than any other author I know.” Adm. William Hannam Henderson agreed: “No nation would permit it, and the officer who did it would be shot.”

But within months the U-boats’ depredations had begun, and by February 1915 Doyle was being accused of suggesting the idea to the Germans. “I need hardly say that it is very painful to me to think that anything I have written should be turned against my own country,” he told a reporter. “The object of the story was to warn the public of a possible danger which I saw overhanging this country and to show it how to avoid that danger.”

“Oh, isn’t it a lovely sunset?” a young woman asked Robert Frost.

He said, “I never discuss business after dinner.”

1916 saw a poetic flowering across the United States — a series of public gardens cultivating the plants mentioned in Shakespeare’s plays, to commemorate the 300th anniversary of the Bard’s death. The one above is at Vassar, but similar installations appeared at Cedar Rapids, Iowa, Rockefeller Park in Cleveland, and Central Park.

New York’s garden filled two acres with violets, wind-flowers, bloodroot, hepatica, rock-dress, English daisies, spring beauties, shooting stars, candytuft, forget-me-nots, and moss pinks, as well as an oak transplanted from Stratford-on-Avon. But its participation is surprising: In 1890 a similarly romantic impulse there had led to much darker results.

Bonus factoid: Shakespeare and Cervantes died on the same date but on different days. How? Both died on April 23, 1616, but at the time England was following the Julian calendar and Spain the Gregorian — a source of oddities in itself.

In 1922, Ernest Hemingway’s wife lost a suitcase full of his early manuscripts at the Gare de Lyons as she was traveling to meet him in Geneva. It was never recovered.

In 1919, T.E. Lawrence misplaced his briefcase while changing trains at Reading railway station. It had contained the first eight books of Seven Pillars of Wisdom. He, too, had to start again.

In 1835, when Thomas Carlyle had finished writing the first volume in his history of the French Revolution, he loaned the manuscript to John Stuart Mill, seeking his opinion. Mill’s maid mistook it for trash and burned it.

“I remember and can still remember less of it than of anything I ever wrote with such toil,” Carlyle wrote in his journal. After laboriously rewriting the volume, he said he felt like a man who had “nearly killed himself accomplishing zero.”

In 1949, New Statesman challenged its readers to parody the style of any novelist named Green or Greene.

Under a pseudonym, Graham Greene submitted a parody of himself:

The child had an air of taking everything in and giving nothing away. At the Rome airport he was led across the tarmac by his aunt, but he seemed to hear nothing of her advice to himself or of the information she produced for the air hostess. He was too busy with his eyes: the hangars had his attention, every lane on the field except his own — that could wait.

‘My nephew,’ she said, ‘yes, that’s him on the list. Roger Court. You will look after him, won’t you? He’s never been quite on his own before,’ but when she made that statement the child’s eyes moved back plane by plane with what looked like contempt, back to the large breasts and the fat legs and the over-responsible mouth: how could she have known, he might have been thinking, how often I am alone?

He came in second.

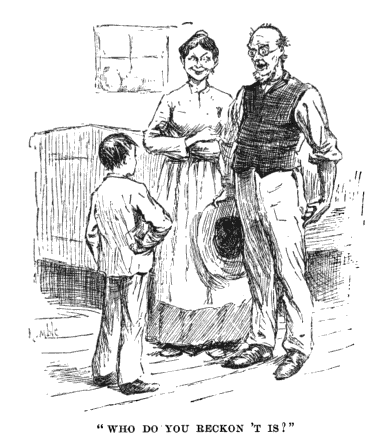

Huckleberry Finn was already in press in 1884 when publisher Charles L. Webster received an alarmed letter from an advance salesman: A mischievous engraver had altered the illustration above to give it a rather darker character (NSFW).

It certainly puts a new spin on the caption.

Despite a reward of $500, the prankster was never identified. Webster had to call back all published copies of the novel, cut out the plate, and tip in a new one, delaying publication past the Christmas season. But it’s fortunate they caught it when they did — it could have ruined Mark Twain’s career.