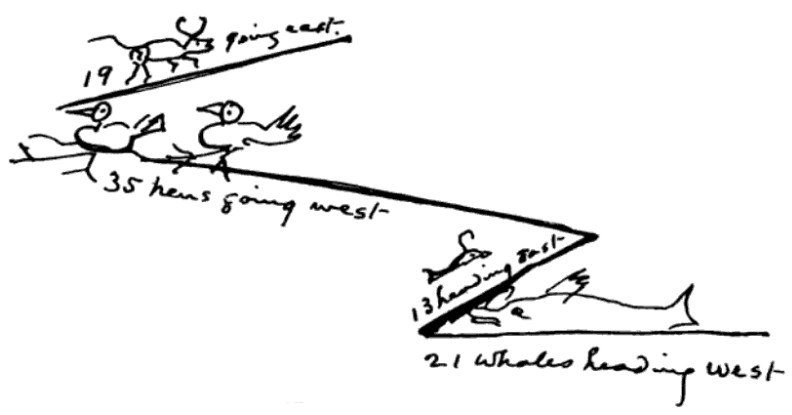

Erasmus’ 1512 rhetoric textbook Copia lists 195 variations on the sentence “Your letter delighted me greatly”:

Your brief note refreshed my spirits in no small measure.

I was in no small measure refreshed in spirit by your grace’s hand.

From your affectionate letter I received unbelievable pleasure.

Your pages engendered in me an unfamiliar delight.

I conceived a wonderful delight from your pages.

Your lines conveyed to me the greatest joy.

The greatest joy was brought to me by your lines.

We derived great delight from your excellency’s letter.

From my dear Faustus’ letter I derived much delight.

In these Faustine letters I found a wonderful kind of delectation.

At your words a delight of no ordinary kind came over me.

I was singularly delighted by your epistle.

To be sure your letter delighted my spirits!

Your brief missive flooded me with inexpressible Joy.

As a result of your letter, I was suffused by an unfamiliar gladness.

Your communication poured vials of joy on my head.

Your epistle afforded me no small delight.

The perusal of your letter charmed my mind with singular delight.

He followed this with 200 variations on the phrase “Always, as long as I live, I shall remember you.”