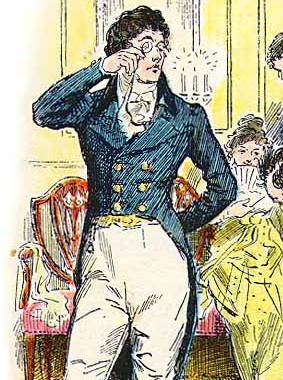

In Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, the residents of Meryton consider Mr. Darcy arrogant, proud, and conceited because of his reactions to village people. Of Elizabeth Bennet he says, “She is tolerable; but not handsome enough to tempt me; and I am in no humour at present to give consequence to young ladies who are slighted by other men.” Later, when she spurns his proposal, he tells her directly, “Nor am I ashamed of the feelings I related. They were natural and just. Could you expect me to rejoice in the inferiority of your connections? To congratulate myself on the hope of relations whose condition in life is so decidedly beneath my own?”

The trouble is, he’s right — Darcy is educated, intelligent, wealthy, and handsome. He is superior to the people he’s judging, even according to their own standards. University of Minnesota philosopher Valerie Tiberius asks, what then is arrogance?

“Henry Kissinger, for instance, is by all accounts a highly arrogant person, but his intellectual talents are considerable, and all philosophical accounts of the good life for human beings assign such talents an important role. … So if Darcy and Kissinger believe that they are doing pretty well by the standards of human excellence, it is not obvious that they are wrong, and their arrogance must therefore consist in something other than a false belief.”

(Valerie Tiberius and John D. Walker, “Arrogance,” American Philosophical Quarterly 35:4 [October 1998], 379-390.)