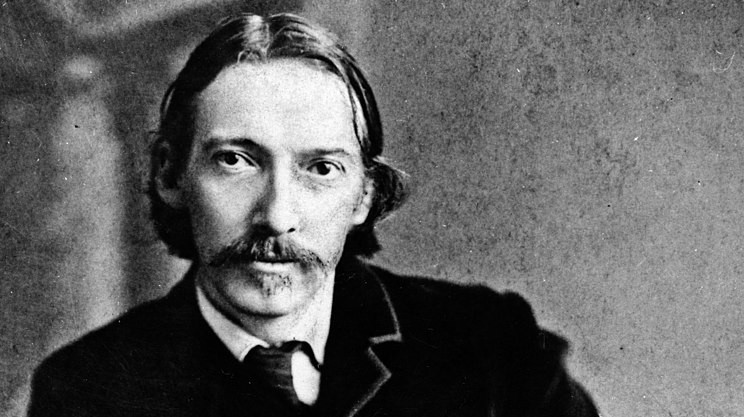

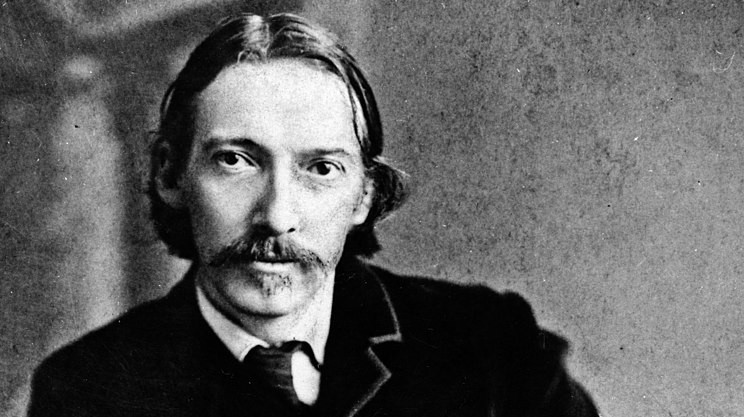

“There is but one art — to omit! O if I knew how to omit, I would ask no other knowledge. A man who knew how to omit would make an Iliad of a daily paper.” — Robert Louis Stevenson, letter to a cousin, Oct. 30, 1883

“There is but one art — to omit! O if I knew how to omit, I would ask no other knowledge. A man who knew how to omit would make an Iliad of a daily paper.” — Robert Louis Stevenson, letter to a cousin, Oct. 30, 1883

In “The Adventure of the Empty House,” an old book collector visits John Watson’s house, “his precious volumes, a dozen of them at least, wedged under his right arm.” He says, “Maybe you collect yourself, sir; here’s British Birds, and Catullus, and The Holy War — a bargain every one of them. With five volumes you could just fill that gap on that second shelf.”

Now, this must mean either that two of the titles comprised two volumes apiece or that one comprised three volumes, a point first made by Magistrate S. Tupper Bigelow. But which is it? In the strangely half-specified world that Holmes and Watson inhabit, the fact of the matter seems not to exist.

Philosopher Terence Parsons asks whether Holmes has a mole on his back. Since the stories are silent on this point, it seems that he neither has one nor doesn’t.

See Truth and Fiction.

“I do not remember this day.” — Dorothy Wordsworth, diary, March 17, 1798

“Such a beautiful day, that one felt quite confused how to make the most of it, and accordingly frittered it away.” — Caroline Fox, diary, January 4, 1848

“I shall not remember what happened on this day. It is a blank. At the end of my life I may want it, may long to have it. There was a new moon: that I remember. But who came or what I did — all is lost. It’s just a day missed, a day crossing the line.” — Katherine Mansfield, diary, Jan. 28, 1920

“Wrote nothing.” — Franz Kafka, diary, June 1, 1912

“I awakened feeling dull. The weather is neither cheerful nor depressing. It makes me restless. The trees are tossed by gusty, fantastic wind. The sun is hidden. If I put on my dressing-gown I am too hot, if I take it off I am cold. Leaden day in which I shall accomplish nothing worth while. Tired and apathetic brain! I have been drinking tea in the hope that it would carry this mood to a climax and so put an end to it.” — George Sand, diary, June 1, 1837

Samuel Johnson resolved 14 times “to keep a journal.” The first resolution was in 1760, the last in 1782.

Beryl Markham managed to fit three extraordinary careers into one lifetime: She was a champion racehorse trainer, a pioneering bush pilot, and a best-selling author. In this week’s episode of the Futility Closet podcast we’ll review her eventful life, including her historic solo flight across the Atlantic in 1936.

We’ll also portray some Canadian snakes and puzzle over a deadly car.

The Society of Actuaries holds a regular speculative fiction contest. Here’s an excerpt from “The Temple of Screens,” by Nate Worrell, FSA, MAAA, recognized last year for describing the “most innovative actuarial career of the future”:

‘Ever since humans began to be aware of a future, we’ve wanted to explore it. We’ve cast stones, searched in tea leaves, held the entrails of animals in our hands to try to extract some knowledge of our fate. Some of our stories try to show us that like Oedipus, we can’t change our fate. In other stories, we find an escape, we have the power of choice, at least to some degree. But in either case, knowing our future changes how we act. Now that you’ve seen your possible futures, they are tainted. If you were to go back in, they’d all change, reflecting that you had some knowledge. The algorithm would reallocate a new set of weights to your tendencies, increasing some behaviors and decreasing others.’

A wave of anger flashes through me, and I stand and start pacing. ‘So what’s the use of this?’

‘To help you embrace what’s possible, to come to terms with it. You came here because you were afraid of a certain future, one you hoped to avoid somehow. We can’t fight or flee from the future, whatever one we fall into. But we can find serenity in any of our futures, if we so desire.’

A little oddity: In Edith Wharton’s The Age of Innocence, a sentence of 16 words (“The change will do you good, and you must be sure to go and see Ellen,” spoken to Newland Archer by his wife May) has a meaning of 221 words:

It was the only word that passed between them on the subject; but in the code in which they had both been trained it meant: ‘Of course you understand that I know all that people have been saying about Ellen, and heartily sympathise with my family in their effort to get her to return to her husband. I also know that, for some reason you have not chosen to tell me, you have advised her against this course, which all the older men of the family, as well as our grandmother, agree in approving; and that it is owing to your encouragement that Ellen defies us all, and exposes herself to the kind of criticism of which Mr. Sillerton Jackson probably gave you, this evening, the hint that has made you so irritable…. Hints have indeed not been wanting; but since you appear unwilling to take them from others, I offer you this one myself, in the only form in which well-bred people of our kind can communicate unpleasant things to each other: by letting you understand that I know you mean to see Ellen when you are in Washington, and are perhaps going there expressly for that purpose; and that, since you are sure to see her, I wish you to do so with my full and explicit approval — and to take the opportunity of letting her know what the course of conduct you have encouraged her in is likely to lead to.’

In 1989, William Faulkner’s niece founded an annual contest to parody her uncle’s distinctive writing style. It ran for 16 years, with the winners published in United Airlines’ Hemispheres magazine. Here’s the winner from 2001, “The (Auto) Pound and the Jury (or Quentin Gets His First Parking Ticket),” by Louisiana Philharmonic clarinetist Allan Kolsky:

For the fifth time in as many minutes, the bright shapes slowly passed us through the somnolent dust, each moving left to right, each in its ordered place. As we (once again) passed beneath the grim and merciless statue of the confederate soldier (that still unravish’d sentinel of quietude, his implacable marble hand forever shading the inscrutable carven eyes) our hearts sank a little deeper, not because we now realized that our quest was futile, but because it always had been, because we now seemed doomed forever to circle this postage stamp of land like slow planets orbiting some inescapable star.

‘Well well well,’ said Ratliff, ‘I reckon thats the fifth time weve been around this square and I still aint seen no parkin space. Why dont you just pull up in front of that fire hydrant — its only for a minute, anyhow.’

And now the musty smell of old leather—the thick, bound books containing what Father once called the sum total of mans ignorance: ceteris paribus and tempus fugit and caveat emptor too, and Oliver Wendell Holmes with Saint Francis himself, who never had a parking ticket and first thing lets kill all the lawyers and i father i have committed grand theft auto and he this looks more like a parking ticket to me and i but are they not the same and he you would take a perfectly common automotive error, an inevitable consequence of operating a motor vehicle and you would make it monstrous and i but it IS monstrous and he its only fifteen dollars, its not exactly the end of the world and i but i have still failed and he arbitrary lines delimiting segments of tarmac, the sum total of mans folly reduced to lines drawn ceteris paribus on some cosmic concrete chalkboard and i but did you ever get one and he of course and i how many times and he you want me to Count—NoCount would ever satisfy you and i but dont you believe in sin and he sin quentin was a term coined by those without courage to describe the actions of those who did indeed possess it and i but then our lives are just and he our lives are just so many tiny clumsy sandcastles before the godless oceans angry tide.

I took the ashtray from the table and I placed it on the floor. Then I realized that I had forgotten the gasoline and so I had to open the cabinet and take the can and remove the cap. The gasoline stung my nostrils as I poured it into the ashtray. I replaced the cap and I put the can back in its cabinet. I placed the parking ticket in the ashtray and I soaked it well with the gasoline. Then I remembered that I needed a match, but my hand had already found the matchbook in my pocket, and so I didnt have to open the cabinet any more.

Alas, the contest has been suspended since 2005, but some of the winners are archived here.

“Two years ago,” she said, “when I was so sick, I realized that I was dreaming the same dream night after night. I was walking in the country. In the distance, I could see a white house, low and long, that was surrounded by a grove of linden trees. To the left of the house, a meadow bordered by poplars pleasantly interrupted the symmetry of the scene, and the tips of the poplars, which you could see from far off, were swaying above the linden.

“In my dream, I was drawn to this house, and I walked toward it. A white wooden gate closed the entrance. I opened it and walked along a gracefully curving path. The path was lined by trees, and under the trees I found spring flowers — primroses and periwinkles and anemones that faded the moment I picked them. As I came to the end of this path, I was only a few steps from the house. In front of the house, there was a great green expanse, clipped like the English lawns. It was bare, except for a single bed of violet flowers encircling it.

“The house was built of white stone and it had a slate roof. The door — a light oak door with carved panels — was at the top of a flight of steps. I wanted to visit the house, but no one answered when I called. I was terribly disappointed, and I ran and I shouted — and finally I woke up.

“That was my dream, and for months it kept coming back with such precision and fidelity that finally I thought: surely I must have seen this park and this house as a child. When I would wake up, however, I could never recapture it in waking memory. The search for it became such an obsession that one summer — I’d learned to drive a little car — I decided to spend my vacation driving through France in search of my dream house.

“I’m not going to tell about my travels. I explored Normandy, Touraine, Poitou, and found nothing, which didn’t surprise me. In October, I came back to Paris, and all through the winter I continued to dream about the white house. Last spring, I resumed my old habit of making excursions in the outskirts of Paris. One day, I was crossing a valley near L’Isle-Adam. Suddenly I felt an agreeable shock — that strange feeling one has when after a long absence one recognizes people or places one has loved.

“Although I had never been in that particular area before, I was perfectly familiar with the landscape lying to my right. The crests of some poplars dominated a stand of linden trees. Through the foliage, which was still sparse, I could glimpse a house. Then I knew that I had found my dream château. I was quite aware that a hundred yards ahead, a narrow road would be cutting across the highway. The road was there. I followed it. It led me to a white gate.

“There began the path I had so often followed. Under the trees, I admired the carpet of soft colors woven by the periwinkles, the primroses, and the anemones. When I came to the end of the row of linden, I saw the green lawn and the little flight of steps, at the top of which was the light oak door. I got out of my car, ran quickly up the steps, and rang the bell.

“I was terribly afraid that no one would answer, but almost immediately a servant appeared. It was a man, with a sad face, very old. He was wearing a black jacket. He seemed very much surprised to see me, and he looked at me closely without saying a word.

“‘I’m going to ask you a rather odd favor,’ I said. ‘I don’t know the owners of this house, but I would be very happy if they would permit me to visit it.’

“‘The château is for rent, madame,’ he said, with what struck me as regret, ‘and I am here to show it.’

“‘To rent?’ I said. ‘What luck! It’s too much to have hoped for. But how is it that the owners of such a beautiful house aren’t living in it?’

“‘The owners did live in it, madame. They moved out when it became haunted.’

“‘Haunted?’ I said. ‘That will scarcely stop me. I didn’t know people in France, even in the country, still believed in ghosts.’

“‘I wouldn’t believe in them, madame,’ he said seriously, ‘if I myself had not met, in the park at night, the phantom that drove my employers away.’

“‘What a story!’ I said, trying to smile.

“‘A story, madame,’ the old man said, with an air of reproach, ‘that you least of all should laugh at, since the phantom was you.'”

— Andre Maurois, 1931

The Sherlock Holmes story “The Adventure of the Priory School” concerns the Duke of Holdernesse and the kidnapping of his son, Lord Saltire. The family name of the duke is never given in the story, but Holmes mentions in “The Adventure of the Blanched Soldier” that his real title is Duke of Greyminster.

Greyminster calls to mind Lord Greystoke, the title of Tarzan’s father, John Clayton, in Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Tarzan adventures. Greystoke is marooned on the west coast of Africa while investigating a political intrigue there, and his wife gives birth to a son who becomes lord of the apes.

Is there a link here? Did Burroughs discreetly alter Clayton’s title from Greyminster to Greystoke in telling his story?

Writing in the Baker Street Journal in 1960, Princeton English professor H.W. Starr points out that John Clayton is also the name of the driver of the cab in which Stapleton trails Sir Henry and Dr. Mortimer in The Hound of the Baskervilles.

That’s an interesting coincidence. Can Tarzan’s father and the cab driver be the same man? No, the timing doesn’t work: Tarzan’s father was marooned in 1888 and never returned to England, and the John Clayton of Baskervilles appears at 221B Baker Street in 1889.

But the cabbie could be Tarzan’s grandfather. In the Tarzan stories, when Tarzan’s father disappears off Africa, the title passes to his younger brother (the cabbie’s other son, in our hypothesis), and we are told that that son bore a son of his own, William Cecil Clayton. William Cecil Clayton was 19 or 20 in 1909, similar to the age of Lord Saltire, the kidnapped son of the Duke of Holdernesse in “Priory.” Starr writes, “This seems too close a correspondence of facts to be mere coincidence.”

If all this is true, and assuming that Burroughs changed “Greyminster” to “Greystoke,” then John Clayton the cab driver is really the fifth Duke of Greyminster, father of two sons: John Clayton (“Lord Greystoke” in Burroughs’ rendering) and the “sixth Duke of Holdernesse” (in Doyle’s rendering). And the “Lord Saltire” who is kidnapped in “The Adventure of the Priory School” is the latter’s son, William Cecil Clayton, seventh Duke and the first cousin of John Clayton III, who is the eighth Duke of Greyminster and Tarzan of the Apes.

(All this might also help to explain Holmes’ whereabouts during his supposed death in the period 1891-1894 — possibly the British government had sent him to Africa to investigate Greystoke’s disappearance.)

(H.W. Starr, “A Case of Identity, or The Adventures of the Seven Claytons,” Baker Street Journal, New Series X, i, January 1960.)

Philip José Farmer hatched an even more elaborate theory in 1972.

At long last, after the three volumes were successfully launched, he became what [C.S.] Lewis called ‘cock-a-hoop’ and talked with great enthusiasm of the fate of the pirated paperback version and the astonishing growth of the Tolkien cult. He enjoyed receiving letters in Elvish from boys at Winchester and from knowing that they were using it as a secret language. He was overwhelmed by his fan mail and would-be visitors. It was wonderful to have at long last plenty of money, more than he knew what to do with. He once began a meeting with me by saying: ‘I’ve been a poor man all my life, but now for the first time I’ve a lot of money. Would you like some?’

— George Sayer, “Recollections of J.R.R. Tolkien,” in Joseph Pearce, ed., Tolkien: A Celebration, 1999