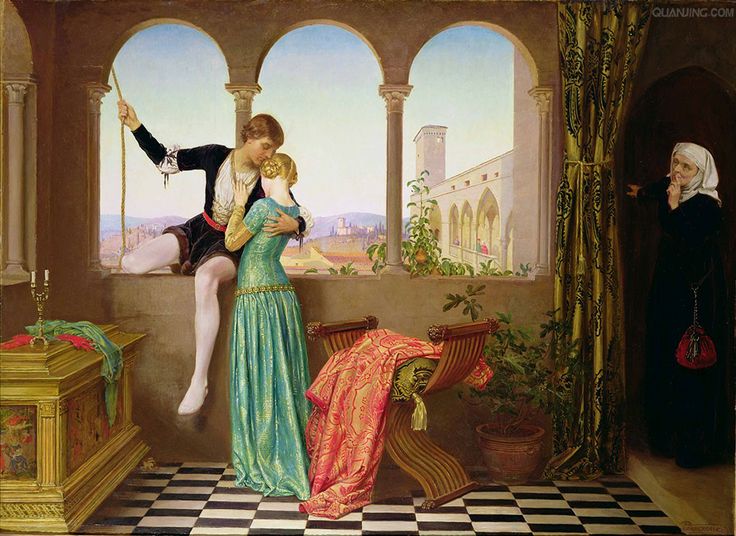

In 1865, while conducting the “Answers to Correspondents” column in The Californian, Mark Twain received this inquiry:

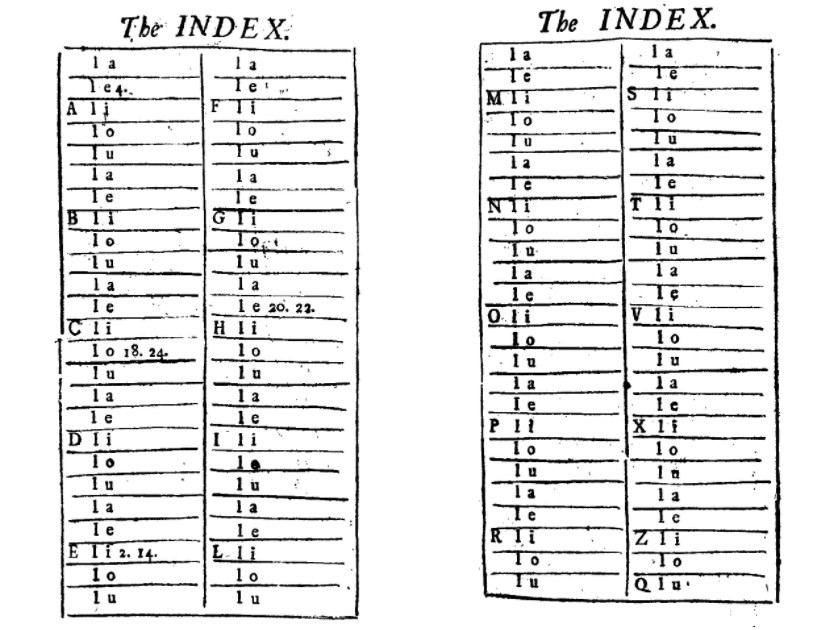

If it would take a cannon ball 3 1/3 seconds to travel four miles, and 3 3/8 seconds to travel the next four, and 3 5/8 to travel the next four, and if its rate of progress continued to diminish in the same ratio, how long would it take it to go fifteen hundred millions of miles?

He responded:

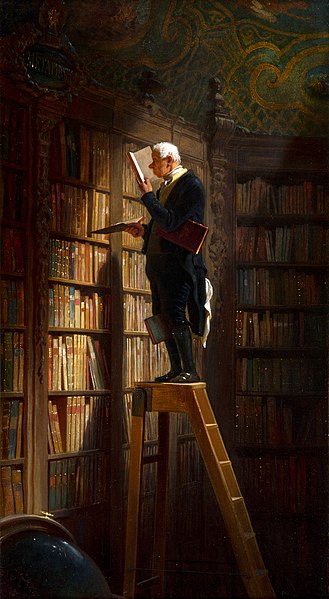

I don’t know.

In a 1906 address to the New York Association for Promoting the Interests of the Blind, he said, “I never could do anything with figures, never had any talent for mathematics, never accomplished anything in my efforts at that rugged study, and today the only mathematics I know is multiplication, and the minute I get away up in that, as soon as I reach nine times seven … [Mr. Clemens lapsed into deep thought for a moment.] I’ve got it now. It’s eighty-four.”