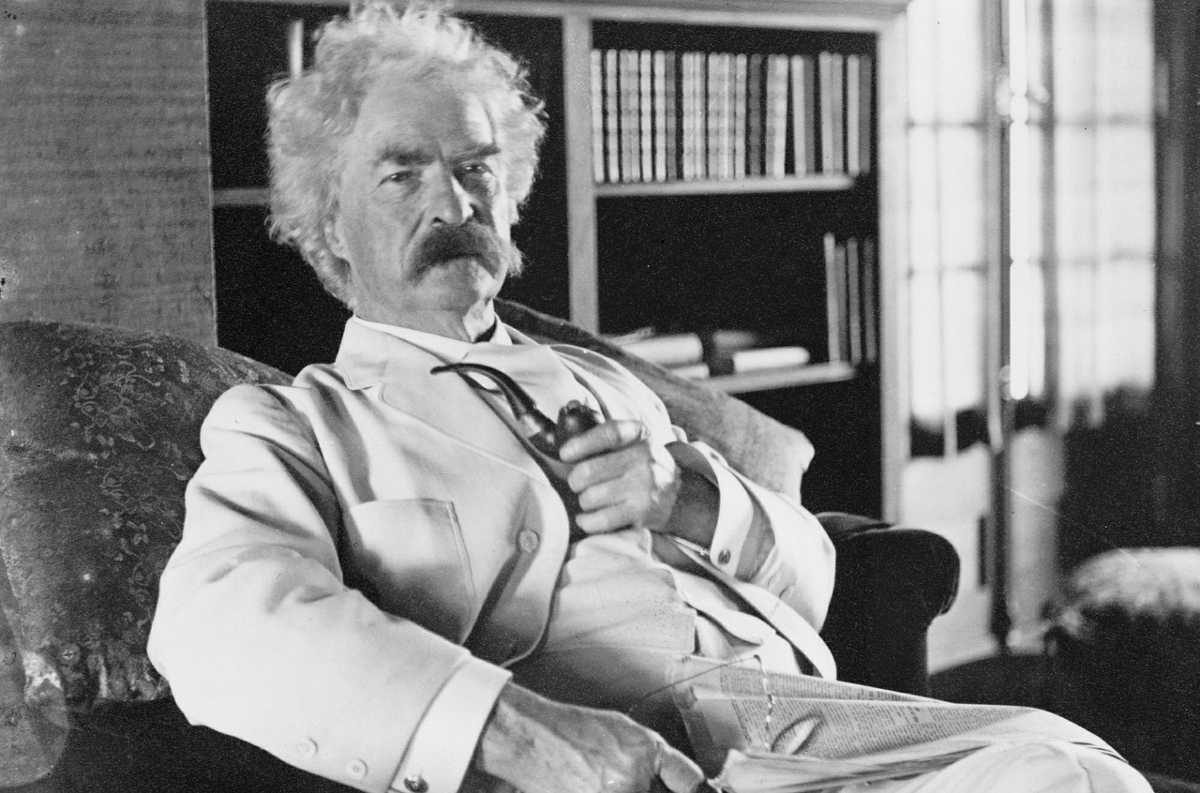

On Nov. 21, 1897, Mark Twain addressed the Vienna Press Club on “The Horrors of the German Language.” He spoke in German; here’s his literal translation:

It has me deeply touched, my gentlemen, here so hospitably received to be. From colleagues out of my own profession, in this from my own home so far distant land. My heart is full of gratitude, but my poverty of German words forces me to great economy of expression. Excuse you, my gentlemen, that I read off, what I you say will.

The German language speak I not good, but have numerous connoisseurs me assured that I her write like an angel. Maybe — I know not. Have till now no acquaintance with the angels had. That comes later — when it the dear God please — it has no hurry.

Since long, my gentlemen, have I the passionate longing nursed a speech on German to hold, but one has me not permitted. Men, who no feeling for the art had, laid me ever hindrance in the way and made naught my desire — sometimes by excuses, often by force. Always said these men to me: ‘Keep you still, your Highness! Silence! For God’s sake seek another way and means yourself obnoxious to make.’

In the present case, as usual it is me difficult become, for me the permission to obtain. The committee sorrowed deeply, but could me the permission not grant on account of a law which from the Concordia demands she shall the German language protect. Du liebe Zeit! How so had one to me this say could — might — dared — should? I am indeed the truest friend of the German language — and not only now, but from long since — yes, before twenty years already. And never have I the desire had the noble language to hurt; to the contrary, only wished she to improve — I would her only reform. It is the dream of my life been. I have already visits by the various German governments paid and for contracts prayed. I am now to Austria in the same task come. I would only some changes effect. I would only the language method — the luxurious, elaborate construction — compress, the eternal parenthesis suppress, do away with, annihilate; the introduction of more than thirteen subjects in one sentence forbid; the verb so far to the front pull that one it without a telescope discover can. With one word, my gentlemen, I would your beloved language simplify so that, my gentlemen, when you her for prayer need, One her yonder-up understands.

I beseech you, from me yourself counsel to let, execute these mentioned reforms. Then will you an elegant language possess, and afterward, when you some thing say will, will you at least yourself understand what you said had. But often nowadays, when you a mile-long sentence from you given and you yourself somewhat have rested, then must you a touching inquisitiveness have yourself to determine what you actually spoken have. Before several days has the correspondent of a local paper a sentence constructed which hundred and twelve words contained, and therein were seven parentheses smuggled in, and the subject seven times changed. Think you only, my gentlemen, in the course of the voyage of a single sentence must the poor, persecuted, fatigued subject seven times change position!

Now, when we the mentioned reforms execute, will it no longer so bad be. Doch noch eins. I might gladly the separable verb also a little bit reform. I might none do let what Schiller did: he has the whole history of the Thirty Years’ War between the two members of a separable verb in-pushed. That has even Germany itself aroused, and one has Schiller the permission refused the History of the Hundred Years’ War to compose — God be it thanked! After all these reforms established be will, will the German language the noblest and the prettiest on the world be.

Since to you now, my gentlemen, the character of my mission known is, beseech I you so friendly to be and to me your valuable help grant. Mr. Potzl has the public believed make would that I to Vienna come am in order the bridges to clog up and the traffic to hinder, while I observations gather and note. Allow you yourselves but not from him deceived. My frequent presence on the bridges has an entirely innocent ground. Yonder gives it the necessary space, yonder can one a noble long German sentence elaborate, the bridge-railing along, and his whole contents with one glance overlook. On the one end of the railing pasted I the first member of a separable verb and the final member cleave I to the other end — then spread the body of the sentence between it out! Usually are for my purposes the bridges of the city long enough; when I but Potzl’s writings study will I ride out and use the glorious endless imperial bridge. But this is a calumny; Potzl writes the prettiest German. Perhaps not so pliable as the mine, but in many details much better. Excuse you these flatteries. These are well deserved.

Now I my speech execute — no, I would say I bring her to the close. I am a foreigner — but here, under you, have I it entirely forgotten. And so again and yet again proffer I you my heartiest thanks.