In 1866, writing in the Virginia City Territorial Enterprise, Mark Twain accused San Francisco police chief Martin Burke of corruption, and “some leather-head” misinterpreted the column to suggest that Burke kept a mistress. Twain wrote to the San Francisco Examiner with a clarification:

EDITOR EXAMINER:–You published the following paragraph the other day and stated that it was an ‘extract from a letter to the Virginia Enterprise, from the San Francisco correspondent of that paper.’ Please publish it again, and put it in the parentheses where I have marked them, so that people who read with wretched carelessness may know to a dead moral certainty when I am referring to Chief Burke, and also know to an equally dead moral certainty when I am referring to the dog:

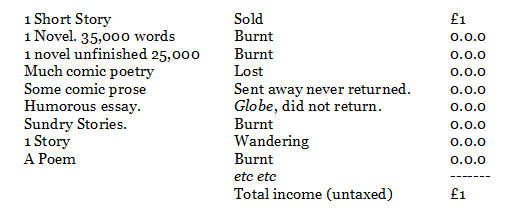

‘I want to compliment Chief Burke — I do honestly. But I can’t find anything to compliment him about. He is always rushing furiously around, like a dog after his own tail — and with the same general result, it seems to me; if he (the dog, not the Chief,) catches it, it don’t amount to anything, after all the fuss; and if he (the dog, not the Chief,) don’t catch it it don’t make any difference, because he (the dog, not the Chief,) didn’t want it anyhow; he (the dog, not the Chief,) only wanted the exercise, and the happiness of “showing off” before his (the dog’s, not the Chief’s,) mistress and the other young ladies. But if the Chief (not the dog,) would only do something praiseworthy, I would be the first and the most earnest and cordial to give him (the Chief, not the dog,) the credit due. I would sling him (the Chief, not the dog,) a compliment that would knock him down. I mean that it would be such a first-class compliment that it might surprise him (the Chief, not the dog,) to that extent as coming from me.’

He added: “I think that even the pupils of the Asylum at Stockton can understand that paragraph now.”