At age 18, James Joyce wrote a play, A Brilliant Career. He began it with an inscription:

To

My own Soul I

dedicate the first

true work of my

life.

It’s the only one of his writings that bears a dedication.

At age 18, James Joyce wrote a play, A Brilliant Career. He began it with an inscription:

To

My own Soul I

dedicate the first

true work of my

life.

It’s the only one of his writings that bears a dedication.

Index entries in John Carey’s The Violent Effigy: A Study of Dickens’ Imagination, 1973:

babies, bottled, 82

begging-letters, 67

beheading, 21

caged birds, 44, 46, 116-19

cannibalism, 22-4, 175

cleanliness, excessive, 36-7

climbing boys, 72

coffins, walking, 80-1

combustible persons, 14, 165

dolls’ houses, 34

dust heaps, 109-11

fire, seeing pictures in, 16

furniture, live, 102-3

grindstones, 129

home-smashing, 17

junk, enchantment of, 49-50

land-ships, 43-6, 49-9

legs, humour of, 61-2, 92-3

mirrored episodes, 125-6

old clothes, 89-91

pokers, red-hot, 26, 85

‘ruffian class,’ the, 38-9

scissored women, 163-4

seedsman’s shops, 45-6, 48

silent laughter, 98-100, 165

snuff, composed of dead bodies, 80

talking birds, 100-1

umbrellas, 128-9

virtuous violence, 28-9

waxworks, 82, 84

wooden legs, 91-3, 103

zoo, feeding time at, 68-9

“It does not matter that Dickens’s world is not lifelike,” wrote Lord David Cecil. “It is alive.”

In 1952 Nancy Mitford asked Evelyn Waugh, “What do you do with all the people who want interviews, with fan letters & with fans in the flesh? Just a barrage of nos?” He responded with his own rules:

(a) Humble expressions of admiration. To these a post-card saying ‘I am delighted to learn that you enjoyed my book. E. W.’

(b) Impudent criticism. No answer.

(c) Bores who wish to tell me about themselves. Post-card saying ‘Thank you for interesting letter. E. W.’

(d) Technical criticism, eg. One has made a character go to Salisbury from Paddington. Post-card: ‘Many thanks for your valuable suggestion. E. W.’

(e) Humble aspirations of would-be writers. If attractive a letter of discouragement. If unattractive a post-card.

(f) Requests from University Clubs for a lecture. Printed refusal.

(g) Requests from Catholic Clubs for lecture. Acceptance.

(h) American students of ‘Creative Writing’ who are writing theses about one & want one, virtually, to write their theses for them. Printed refusal.

(i) Tourists who invite themselves to one’s house. Printed refusal.

(j) Manuscript sent for advice. Return without comment. …

(k) Autograph collectors: no answer.

(l) Indians & Germans asking for free copies of one’s books: no answer.

(m) Very rich Americans: polite letter. They are capable of buying 100 copies for Christmas presents.

“In case of very impudent letters from married women I write to the husband warning him that his wife is attempting to enter into correspondence with strange men. … I think that more or less covers the field.”

Jane Austen is to me the greatest wonder amongst novel writers. I do not mean that she is the greatest novel writer, but she seems to me the greatest wonder. Imagine, if you were to instruct an author or an authoress to write a novel under the limitations within which Jane Austen writes! Supposing you were to say, ‘Now, you must write a novel, but you must have no heroes or heroines in the accepted sense of the word. You may have naval officers, but they must always be on leave or on land, never on active service. You must have no striking villains; you may have a mild rake, but keep him well in the background, and if you are really going to produce something detestable, it must be so because of its small meannesses, as, for instance, the detestable Aunt Norris in ‘Mansfield Park’; you must have no very exciting plot; you must have no thrilling adventures; a sprained ankle on a country walk is allowable, but you must not go much beyond this. You must have no moving descriptions of scenery; you must work without the help of all these; and as to passion, there must be none of it. You may, of course, have love, but it must be so carefully handled that very often it seems to get little above the temperature of liking. With all those limitations you are to write, not only one novel, but several, which, not merely by popular appreciation, but by the common consent of the greatest critics, the greatest literary minds of the generations which succeed you, shall be classed among the first rank of the novels written in your language in your country.’ Of course, it is possible to say that Jane Austen achieves this, though her materials are so slight because her art is so great. Perhaps, however, so long as the materials are those of human nature, they are not slight.

— Viscount Grey of Fallodon, Fallodon Papers, 1926

Notable expressions of dismay made by Panurge during a tempest at sea in Gargantua and Pantagruel:

Ughughbubbubughsh!

Augkukshw!

Bgshwogrbuh!

Abubububugh!

Bububbububbubu! boo-hoo-hoo-hoo!

Ubbubbughschwug!

Ubbubbugshwuplk!

ubbubbubbughshw

bubbubughshwtzrkagh!

Alas, alas! ubbubbubbugh! bobobobobo! bubububuss!

Ubbubbughsh! Grrrshwappughbrdub!

Bubububbugh! boo-hoo-hoo!

Ubbubbubbugh! Grrwh! Upchksvomitchbg!

Ububbubgrshlouwhftrz!

Ubbubbububugh! ugg! ugg!

Ubbubbubbugh! Boo-hoo-hoo!

“My personal favorite, however, is the incredible-sounding ‘Wagh, a-grups-grrshwahw!’,” writes wordplay enthusiast Trip Payne. “Aside from its logological interest (eight consecutive consonants, albeit divided by a hyphen), the word simply does not sound anything like a wail could possibly sound. The ingenuity of Panurge to come up with such a fresh-sounding, imaginative exclamation — particularly under such pressure — is awe-inspiring.” (All these expressions are from Jacques Leclercq’s 1936 translation.)

(Trip Payne, “‘Alas, Alack!’ Revisited,” Word Ways 22:1 [February 1989], 34-35.)

Corresponding with the Daily Mail in 1933, Compton Mackenzie presented two lists of the 10 most beautiful words in English. The first was phrased in blank verse:

Carnation, azure, peril, moon, forlorn,

Heart, silence, shadow, April, apricot.

The second was an Alexandrine couplet:

Damask and damson, doom and harlequin and fire,

Autumnal, vanity, flame, nectarine, desire.

In his 1963 autobiography he said that these lists had a “strange magic for me … a sort of elixir of youth.” See Euphony and Poetry Piecemeal.

Sydney Smith suggested this inscription for William Pitt’s statue in Hanover Square:

To the Right Honourable William Pitt

Whose errors in foreign policy

And lavish expenditure of our Resources at home

Have laid the foundation of National Bankruptcy

And scattered the seeds of Revolution,

This Monument was erected

By many weak men, who mistook his eloquence for wisdom

And his insolence for magnanimity,

By many unworthy men whom he had ennobled,

And by many base men, whom he had enriched at the Public Expense.

But for Englishmen

This Statue raised from such motives

Has not been erected in vain.

They learn from it those dreadful abuses

Which exist under the mockery

Of a free Representation,

And feel the deep necessity

Of a great and efficient Reform.

“He was one of the most luminous, eloquent blunderers with which any people was ever afflicted,” Smith wrote. “God send us a stammerer; a tongueless man.”

A striking passage from Avrahm Yarmolinsky’s 1959 biography of Ivan Turgenev:

By the end of May [1840] the traveler was back in Berlin. Before he reached the capital he touched at Leghorn, Pisa, Genoa, sailed on Lago Maggiore, traveled to St. Gotthard in a sleigh, visited Lucerne, Basel, Mannheim, Mainz, Frankfort and Leipzig, all within thirteen days. In the same period he managed to lose an umbrella, a cloak, a box, a walking stick, an opera glass, a hat, a pillow, a pen knife, a purse, three towels, two neckerchiefs, two shirts, and, for a short time, his heart.

He had entered a brief affair with Mikhail Bakunin’s sister Tatyana, but passed just as quickly out of it. “I never loved any woman more than you,” he wrote her, “though I don’t love even you with a complete and steadfast love.”

Pekwachnamaykoskwaskwaypinwanik Lake is a lake in Manitoba. Its name is Cree for “where the wild trout are caught by fishing with hooks.”

Muckanaghederdauhaulia, a townland in County Galway, means “pig-marsh between two sea inlets.”

Saaranpaskantamasaari, an island in northeastern Finland, means “an island shat by Saara.”

Mamungkukumpurangkuntjunya is a hill in South Australia. Its name means “where the devil urinates.”

(Thanks, Colin.)

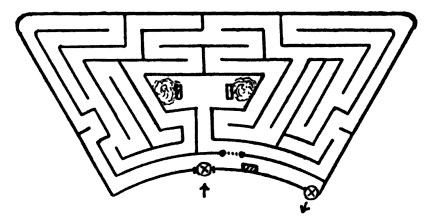

Henry James told Austin Dobson he’d been lost in the maze at Hampton Court.

“I am surprised at that,” Dobson answered. “I should have thought you would have felt that you were in the middle of one of your sentences.”

(From a letter of Harold J. Laski to Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., Dec. 1, 1925. See Homage, A Prose Maze, Stops and Starts, and Thank You for Your Submission.)