For 500 years it was thought that Geoffrey Chaucer had written The Testament of Love, a medieval dialogue between a prisoner and a lady.

But in the late 1800s, British philologists Walter Skeat and Henry Bradshaw discovered that the initial letters of the poem’s sections form an acrostic, spelling “MARGARET OF VIRTU HAVE MERCI ON THINUSK” [“thine Usk”].

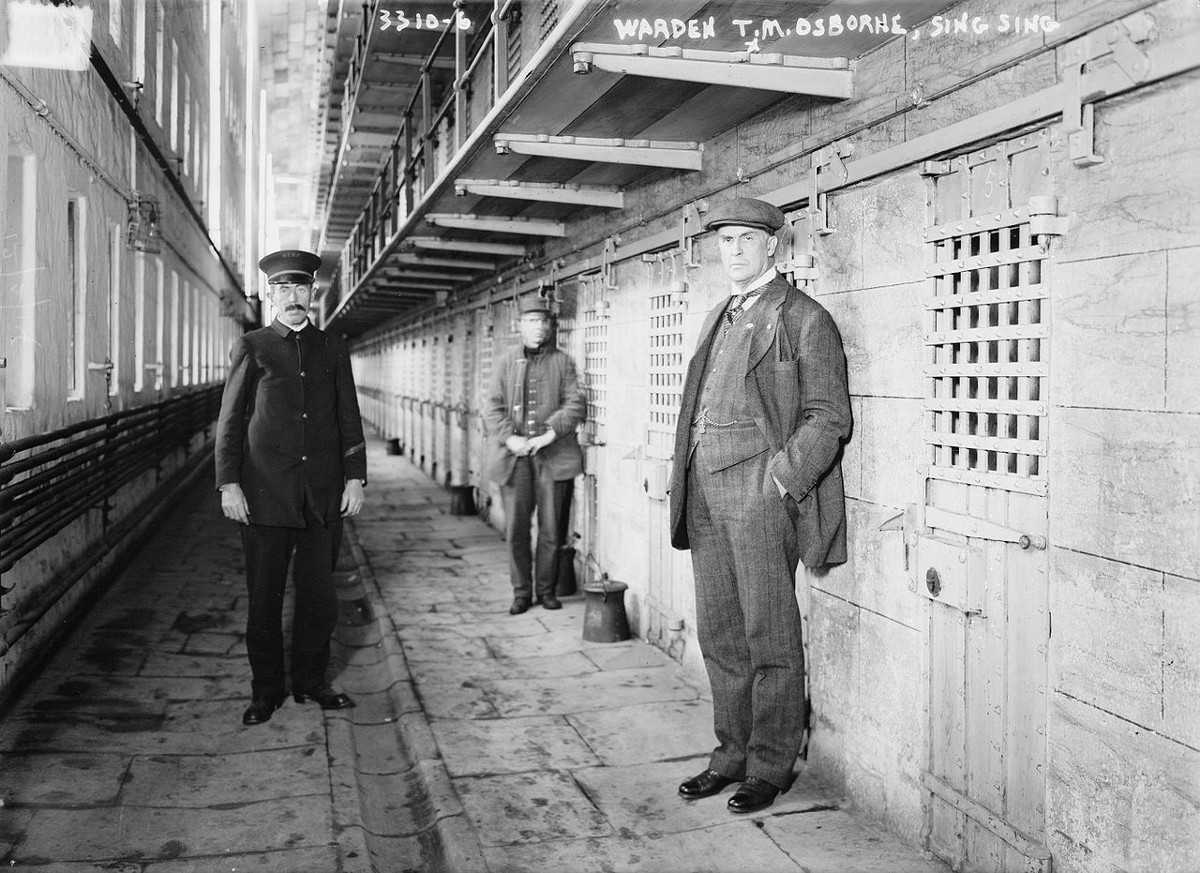

It’s now thought that the poem’s true author was Thomas Usk, a contemporary of Chaucer who was accused of conspiring against the duke of Gloucester. Apparently he had written the Testament in prison in an attempt to seek aid — Margaret may have been Margaret Berkeley, wife of Thomas Berkeley, a literary patron of the time.

If it’s aid that Usk was seeking, he never found it: He was hanged at Tyburn in March 1388.