From the postscript to a 1737 letter by Jonathan Swift — “Here is a rhyme; it is a satire on an inconstant lover.”

You are as faithless as a Carthaginian,

To love at once Kate, Nell, Doll, Martha, Jenny, Anne.

From the postscript to a 1737 letter by Jonathan Swift — “Here is a rhyme; it is a satire on an inconstant lover.”

You are as faithless as a Carthaginian,

To love at once Kate, Nell, Doll, Martha, Jenny, Anne.

Today marks the 400th anniversary of William Shakespeare’s death. To commemorate it, Craig Knecht has devised a 44 × 44 magic square (click to enlarge). Like the squares we featured in 2013, this one is topographical — if the number in each cell is taken to represent its altitude, and if water runs “downhill,” then a fall of rain will produce the pools shown in blue, recalling the words of Griffith in Henry VIII:

Noble madam,

Men’s evil manners live in brass; their virtues

We write in water.

The square includes cells (in light blue) that reflect the number of Shakespeare’s plays (38) and sonnets (154) and the year of his death (1616).

(Thanks, Craig.)

In 1956 Macedonian poet Venko Markovski was imprisoned under a fictitious name for circulating a poem critical of Marshal Tito.

Among the guards were individuals who were taking correspondence courses in an attempt to earn a degree. One of these guards, knowing I was a writer, came up to me one day and said: ‘I was told you are a writer. You have knowledge of literature. I have a request …’

‘Please, what do you want to know about literature?’

‘Tell me about Macedonian literature.’

‘Whom are you interested in?’

‘Venko Markovski.’

‘Is it possible you don’t recognize Venko Markovski?’

‘I don’t know him.’

There was an unpleasant pause. I felt sorry for this man who was ordered to guard someone without knowing whom he was guarding. I spoke to him as follows:

‘The best way for you to learn about Venko Markovski is to read his poetry written in Croatian. In this way you will understand Markovski the poet, the Partisan, the public figure, and you will pass your exam easily. But if you rely on me to tell you about Venko Markovski, you will find yourself — after you fail your exam — in the very place where Markovski now finds himself.’

‘What do you mean by that?’ the guard asked. ‘Where is he in fact?’

‘Right in front of you, here on Goli Otok.’

‘Can it be that you are really he?’

‘Yes, I am here under another name.’

The guard walked away silent and confused.

“The warden obviously thought that since he had physical possession of his prisoners he disposed of their minds and souls as well,” Markovski wrote after gaining his freedom in 1961. “But he was mistaken; the body is one thing and the soul is another. There is no way to bribe the human conscience once it has committed itself to the struggle for the rights of its people.”

(From Geoffrey Bould, ed., Conscience Be My Guide: An Anthology of Prison Writings, 2005.)

From C.S. Lewis’ A Grief Observed, a collection of reflections on the loss of his wife, Joy, in 1960:

It is hard to have patience with people who say ‘There is no death’ or ‘Death doesn’t matter.’ There is death. And whatever is matters. And whatever happens has consequences, and it and they are irrevocable and irreversible. You might as well say that birth doesn’t matter. I look up at the night sky. Is anything more certain that in all those vast times and spaces, if I were allowed to search them, I should nowhere find her face, her voice, her touch? She died. She is dead. Is the word so difficult to learn? …

Talk to me about the truth of religion and I’ll listen gladly. Talk to me about the duty of religion and I’ll listen submissively. But don’t come talking to me about the consolations of religion or I shall suspect that you don’t understand.

He published it originally under the pseudonym N.W. Clerk, a pun on the Old English for “I know not what scholar.”

Spanish artist Jaume Plensa created El Alma del Ebro, above, for a 2008 exposition in Zaragoza on water and sustainable development. (The Ebro River passes through the city.) Visitors can pass in and out of the 11-meter seated figure, but no one has discovered a meaning in the letters that compose it.

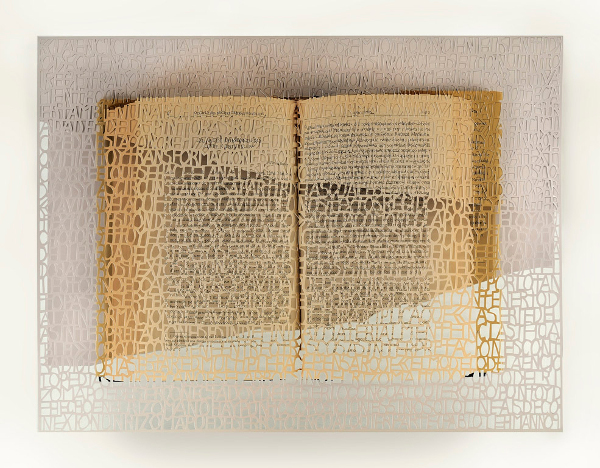

Argentine artist Pablo Lehmann cuts words out of (and into) paper and fabric — he spent two years fashioning an entire apartment out of his favorite philosophy books. Reading and Interpretation VIII, above, is a photographic print of Jorge Luis Borges’ “The Garden of Forking Paths” into which Lehmann has cut his own text — a meditation on “the concept of ‘text.'”

In 2011, Buenos Aires native Marta Minujin built a seven-story “Tower of Babel” on a public street to celebrate the city’s designation as a “world book capital.” The tower, 82 feet tall, was made of 30,000 books donated by readers, libraries, and 50 embassies. They were given away to the public after the exhibition.

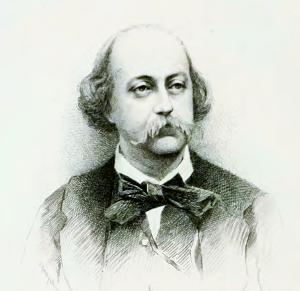

At his death in 1880, Gustave Flaubert left behind notes for a Dictionary of Received Ideas, a list of the trite utterances that people repeat inevitably in conversation:

“All our trouble,” he wrote to George Sand, “comes from our gigantic ignorance. … When shall we get over empty speculation and accepted ideas? What should be studied is believed without discussion. Instead of examining, people pontificate.”

(Thanks, Macari.)

Asteroid 46610 was named Bésixdouze in homage to Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s character Le Petit Prince, who lived on Asteroid B-612.

B-612 is 46610 in hexadecimal.

(Thanks, Dan.)

When Michael Hordern took on the role of King Lear, he asked John Gielgud whether he had any advice to help him get through the run.

“Yes,” Gielgud said. “Get a small Cordelia.”

Ian Fleming never describes James Bond’s physical appearance in any detail, so in December 1962, before the release of the first Bond film, Dr. No, Playboy art director Arthur Paul sent an inquiry to his office. He received this reply:

Dear Mr. Paul,

As Mr. Fleming is away from London I sent him your letter and here now is his description of James Bond:

Height: 6 ft 1 in.

Build: Slim hips, broad shoulders

Eyes: Steely blue-grey

Hair: Black, with comma over right forehead

Weight: 12 stone 8 lb.

Age: Middle thirtiesFeatures:

Determined chin, rather cruel mouth.

Scar down right cheek from cheekbone.

CleanshavenApparel:

Wears two-button single-breasted suit in dark blue tropical worsted. Black leather belt.

White Sea Island cotton shirt, sleeveless.

Black casual shoes, square toed

Thin black knitted silk tie, no pin

Dark blue socks, cotton lisle.

No handkerchief in breast pocket

Wear Rolex Oyster Perpetual watchI hope this information is sufficient for your purpose.

Yours sincerely,

[unsigned]

Secretary to Ian Fleming

From Henry Chancellor, James Bond: The Man and His World, 2005.

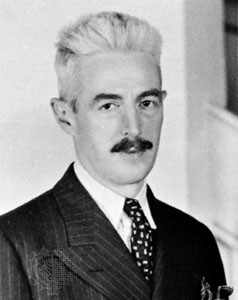

A few adventures of Dashiell Hammett, who worked for the Pinkerton Detective Agency before turning to fiction:

Interestingly, he notes that “the chief difference between the exceptionally knotty problem confronting the detective of fiction and that facing the real detective is that in the former there is usually a paucity of clues, and in the latter altogether too many.”

(“From the Memoirs of a Private Detective,” The Smart Set, March 1923.)