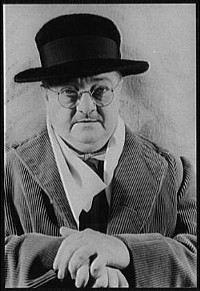

Alexander Woollcott set a world record for the shortest review of a Broadway play.

The play was titled Wham!

Woollcott’s review, in full, read “Ouch!”

Alexander Woollcott set a world record for the shortest review of a Broadway play.

The play was titled Wham!

Woollcott’s review, in full, read “Ouch!”

Nominations are currently open for the 2014 Bookseller/Diagram Prize for oddest book title of the year. This year’s candidates:

Recent winners have included How to Poo on a Date, by Mats & Enzo (2013), Goblinproofing One’s Chicken Coop, by Reginald Bakeley (2012), Cooking With Poo, by Saiyuud Diwong (2011), Managing a Dental Practice: The Genghis Khan Way, by Michael R. Young (2010), and Crocheting Adventures With Hyperbolic Planes, by Daina Taimina (2009).

You can vote here. “This is one of strongest years I have seen in more than three decades of administering the prize, which highlights the crème de la crème of unintentionally nonsensical, absurd and downright head-scratching titles,” said The Bookseller‘s Horace Bent, who organizes the contest. “Let other awards cheer the contents within, the Diagram will always continually judge the book by its cover (title).”

No one knows whether Andrew Jackson was born in North Carolina or South Carolina. The border hadn’t been surveyed well at the time.

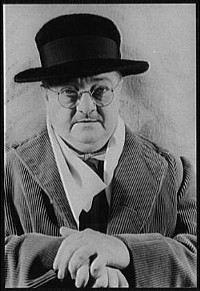

On June 29, 1851, phrenologist J.P. Browne examined a subject he knew only as a “gentlewoman”:

In its intellectual development this head is very remarkable. The forehead is at once very large and well formed. It bears the stamp of deep thoughtfulness and comprehensive understanding. … This lady possesses a fine organ of language, and can, if she has done her talents justice by exercise, express her sentiments with clearness, precision, and force — sufficiently eloquent but not verbose. In learning a language she would investigate its spirit and structure. … In analyzing the motives of human conduct, this lady would display originality and power.

The subject was Charlotte Brontë. She had attended the reading with George Smith, presenting themselves as “Mr. and Miss Fraser.” Phrenology was fashionable at the time, and Charlotte, like many others, was willing to overlook its failures to appreciate its successes. Smith’s reading said, “He is an admirer of the fair sex. He is very kind to children. … Is active and practical though not hustling or contentious.” Smith found this “not so happy,” but Charlotte said, “It is a sort of miracle — like — like — like as the very life itself.”

Another of these dreams he had used as a basis for ‘Pickman’s Model,’ while still another formed the nucleus for ‘The Call of Cthulhu.’ I referred to this story one day, pronouncing the strange word as though it were spelled K-Thool-Hoo. Lovecraft looked blank for an instant, then corrected me firmly, informing me that the word was pronounced, as nearly as I can put it down in print, K-Lütl-Lütl. I was surprised, and asked why he didn’t spell it that way if such was the pronunciation. He replied in all seriousness that the word was originated by the denizens of his story and that he had only recorded their own way of spelling it. Lovecraft’s own invention had assumed an actual reality in his mind.

— Donald Wandrei, “Lovecraft in Providence,” in Peter Cannon, ed., Lovecraft Remembered, 1998

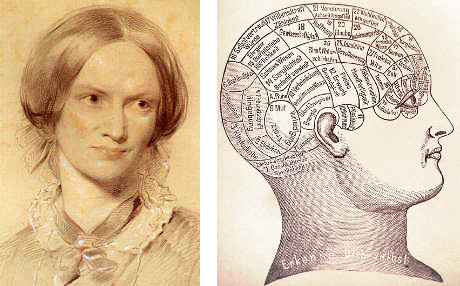

Victorian children’s author Favell Lee Mortimer published three bizarre travel books that described a world full of death, vice, and peril. In this week’s episode of the Futility Closet podcast we’ll sample her terrifying descriptions of the lands beyond England and wonder what led her to write them.

We’ll also review the movie career of an Alaskan sled dog, learn about the Soviet Union’s domestication of silver foxes, and puzzle over some curious noises in a soccer stadium.

Walter Scott’s 1816 novel The Antiquary met with rapturous praise — the Edinburgh Review pronounced the chapter on the escape from the tide to be “the very best description we have ever met, in verse or in prose, in ancient or in modern writing.”

But, critic Andrew Lang quietly noted, “No reviewer seems to have noticed that the sun is made to set in the sea, on the east coast of Scotland.”

Asked for his opinion of Crime and Punishment, Paul Dirac said, “He describes a sunset, and then a little later the same evening the sun sets again. That kind of mistake does jar on me.”

By Colorado classics teacher Jeremy Boor:

MP3, lyrics, and chords are on his website.

In ordinary life we shift frequently between observing the world before us and summoning impressions from memory. Reproducing this experience in fiction can require an immense sophistication of the reader. In Narrative Discourse: An Essay in Method (1983), Gérard Genette examines a passage from Proust’s Jean Santeuil in which Jean finds the hotel in which lives Marie Kossichef, whom he once loved, and compares his impressions with those that he once thought he would experience today:

“Sometimes passing in front of the hotel he remembered the rainy days when he used to bring his nursemaid that far, on a pilgrimage. But he remembered them without the melancholy that he then thought he would surely someday savor on feeling that he no longer loved her. For this melancholy, projected in anticipation prior to the indifference that lay ahead, came from his love. And this love existed no more.”

Understanding this one paragraph requires shifting our focus between the present and the past nine times. If we designate the sections by consecutive letters, and if 1 is “once” and 2 is “now,” then A goes in position 2 (“Sometimes passing in front of the hotel he remembered”), B goes in position 1 (“the rainy days when he used to bring his nursemaid that far, on a pilgrimage”), C in 2 (“But he remembered them without”), D in 1 (“the melancholy that he then thought”), E in 2 (“he would surely some day savor on feeling that he no longer loved her”), F in 1 (“For this melancholy, projected in anticipation”), G in 2 (“prior to the indifference that lay ahead”), H in 1 (“came from his love”), and I in 2 (“And his love existed no more”).

This produces a perfect zigzag: A2-B1-C2-D1-E2-F1-G2-H1-I2. And defining the relationships among the elements reveals even more complexity:

If we take section A as the narrative starting point, and therefore as being in an autonomous position, we can obviously define section B as retrospective, and this retrospection we may call subjective in the sense that it is adopted by the character himself, with the narrative doing no more than reporting his present thoughts (‘he remembered …’); B is thus temporally subordinate to A: it is defined as retrospective in relation to A. C continues with a simple return to the initial position without subordination. D is again retrospective, but this time the retrospection is adopted directly by the text: apparently it is the narrator who mentions the absence of melancholy, even if this absence is noticed by the hero. E brings us back to the present, but in a totally different way from C, for this time the present is envisaged as emerging from the past and ‘from the point of view’ of that past: it is not a simple return to the present but an anticipation (subjective, obviously) of the present from within the past; E is thus subordinated to D as D is to C, whereas C, like A, was autonomous. F brings us again to position 1 (the past), on a higher level than anticipation E: simple return again, but return to 1, that is, to a subordinate position. G is again an anticipation, but this time an objective one, for the Jean of the earlier time foresaw the end that was to come to his love precisely as, not indifference, but melancholy at loss of love. H, like F, is a simple return to 1. I, finally, is (like C), a simple return to 2, that is, to the starting point.

All in a passage of 71 words! And Genette points out in passing that a first reading is made even more difficult because of the apparently systematic way in which Proust eliminates simple temporal indicators such as once and now, “so that the reader must supply them himself in order to know here he is.”

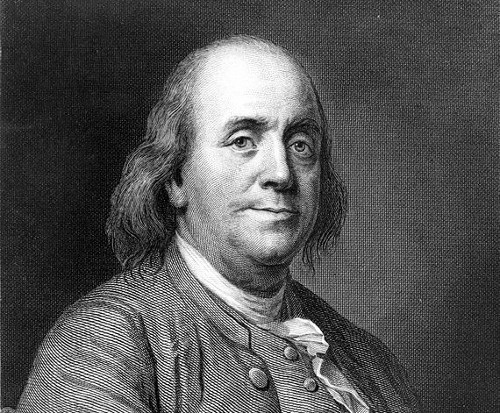

As a young man, Benjamin Franklin drew up a “plan for attaining moral perfection” based on a list of 13 virtues. Half a century later he credited the plan for much of his success in life. In this episode of the Futility Closet podcast we’ll explore Franklin’s self-improvement plan and find out which vices gave him the most trouble.

We’ll also learn how activist Natan Sharansky used chess to stay sane in Soviet prisons and puzzle over why the Pentagon has so many bathrooms.