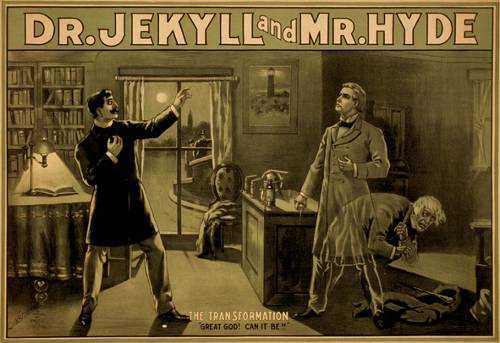

Letter to the Times, Nov. 28, 1980:

Sir,

Mr Roger Lancelyn Green (25 November) asks whether it is known how Robert Louis Stevenson intended the name of Dr Jekyll should be pronounced. Fortunately a reporter from the San Francisco Examiner, who interviewed Stevenson in his hotel bedroom in San Francisco on 7 June 1888, asked him that very question:

‘There has been considerable discussion, Mr Stevenson, as to the pronunciation or Dr Jekyll’s name. Which do you consider to be correct?’

Stevenson (described as propped up in bed ‘wearing a white woollen nightdress and a tired look’) replied: ‘By all means let the name be pronounced as though it spelt “Jee-kill”, not “Jek-ill”. Jekyll is a very good family name in England, and over there it is pronounced in the manner stated.’

Yours faithfully,

Ernest Mehew