The shortest named speaking role in Shakespeare is that of Taurus in Antony and Cleopatra.

He says, “My lord?”

The shortest named speaking role in Shakespeare is that of Taurus in Antony and Cleopatra.

He says, “My lord?”

In 2002, Russian magnate Vladimir O. Potanin paid $1 million for Kazimir Malevich’s 1915 painting Black Square. “‘All paintings are pictures’ would have been a strong candidate for a necessary truth until Malevich proved it false,” wrote Arthur Danto of the inscrutable black canvas. Malevich himself had said, “It is not painting; it is something else.”

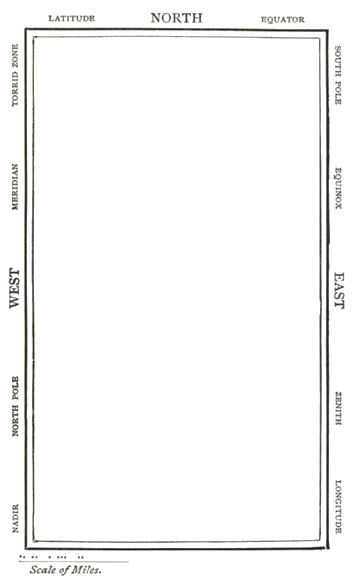

In The Hunting of the Snark, the Bellman guides his party across the Ocean with “a map they could all understand”:

“What’s the good of Mercator’s North Poles and Equators,

Tropics, Zones, and Meridian Lines?”

So the Bellman would cry: and the crew would reply

“They are merely conventional signs!

“Other maps are such shapes, with their islands and capes!

But we’ve got our brave Captain to thank”

(So the crew would protest) “that he’s bought us the best —

A perfect and absolute blank!”

While an architecture student at Cornell in the 1920s, practical joker Hugh Troy was given 48 hours to render “a conception of what a brightly floodlighted hydroelectric plant might look like at night.” “Though Hugh was overloaded with other work, he got his drawing in on time,” remembered classmate Don Hershey. He called it Hydroelectric Plant at Night (Fuse Blown):

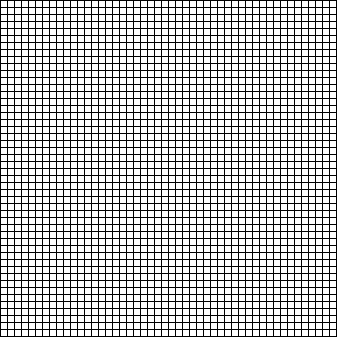

In 1967 British artists Terry Atkinson and Michael Baldwin produced a “map of itself,” a “map of an area of dimensions 12″ x 12″ indicating 2,304 1/4″ squares”:

Katharine Harmon, in The Map as Art, writes that this is one of a series of maps “revealing only what they wished to show and jettisoning the rest — drawing attention to what cartographers have always done.”

(Thanks, Tristram.)

In 1928, theologian and mystery writer Ronald Knox codified 10 rules of detective fiction:

These came to define the “golden age” of the classic murder mystery. The story, Knox wrote, “must have as its main interest the unravelling of a mystery; a mystery whose elements are clearly presented to the reader at an early stage in the proceedings, and whose nature is such as to arouse curiosity, a curiosity which is gratified at the end.”

The first recorded performance of Hamlet took place at sea, aboard the East India ship Red Dragon off the coast of Africa in 1607. Capt. William Keeling’s diary entry for Sept. 5 reads: “I sent the interpreter according to his desier abord the Hector whear he brooke fast and after came abord me wher we gave the tragedie of Hamlett.”

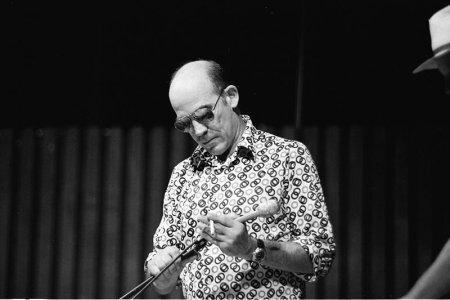

When Hunter S. Thompson published Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, writers began to send him manuscripts, hoping he could help to get them published in Rolling Stone. Thompson sent a package of their poems to the magazine’s poetry editor, Charles Perry. “I don’t know about this stuff,” he wrote. “If you feel the same way, send it back to them with this” — and he included a prepared rejection letter:

You worthless, acid-sucking piece of illiterate shit! Don’t ever send this kind of brain-damaged swill in here again. If I had the time, I’d come out there and drive a fucking wooden stake into your forehead. Why don’t you get a job, germ? Maybe delivering advertising handouts door to door, or taking tickets for a wax museum. You drab South Bend cocksuckers are all the same; like those dope-addled dingbats at the Rolling Stone office. I’d like to kill those bastards for sending me your piece … and I’d just as soon kill you, too. Jam this morbid drivel up your ass where your readership will better appreciate it.

“We actually sent it out to a couple of people, thinking they would appreciate it,” Perry recalled later. “One person took it to a lawyer and asked whether he could sue us, and the lawyer said, ‘No, you don’t have a leg to stand on … but could I Xerox it?'”

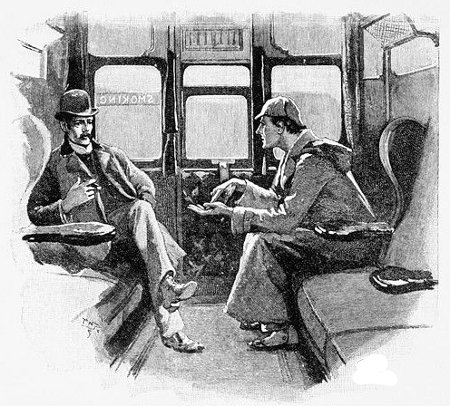

Writings of Sherlock Holmes, compiled by Vincent Starrett in The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes:

In June 1955, a document purporting to be Holmes’ last will and testament was published by Nathan L. Bengis in the London Mystery Magazine. In it, Holmes leaves “to the authorities of Scotland Yard, one copy of each of my trifling monographs on crime detection, unless happily they shall feel they have outgrown the need for the elementary suggestions of an amateur detective.”

Charles Dickens to London clockmaker John Bennett:

My Dear Sir — Since my hall clock was sent to your establishment to be cleaned it has gone (as indeed it always has) perfectly well, but has struck the hours with great reluctance; and, after enduring internal agonies of a most distressing nature, it has now ceased striking altogether. Though a happy release for the clock, this is not convenient to the household. If you can send down any confidential person with whom the clock can confer, I think it may have something on its works that it would be glad to make a clean breast of.

W.S. Gilbert to the Times:

Sir, — Allow me to corroborate Dean Gregory’s statement as to the degeneration that has overtaken a company [the London and Northwestern Railway] which, until recently, was justly regarded as a pattern to all other lines in the matter of punctuality and rapidity of despatch. … In the face of Saturday the officials of the company stand helpless and appalled. This day, which recurs at stated and well-ascertained intervals, is treated as a phenomenon entirely outside the ordinary operations of nature, and, as a consequence, no attempt whatever is made to grapple with its inherent difficulties. To the question, ‘What has caused the train to be so late?’ the officials reply, ‘It is Saturday’ — as who should say, ‘It is an earthquake.’

Mark Twain to a gas and electric lighting company in Hartford, Conn.:

Gentlemen, — There are but two places in our whole street where lights could be of any value, by any accident, and you have measured and appointed your intervals so ingeniously as to leave each of those places in the centre of a couple of hundred yards of solid darkness. When I noticed that you were setting one of your lights in such a way that I could almost see how to get into my gate at night, I suspected that it was a piece of carelessness on the part of the workmen, and would be corrected as soon as you should go around inspecting and find it out. My judgment was right; it is always right, when you are concerned. For fifteen years, in spite of my prayers and tears, you persistently kept a gas lamp exactly half way between my gates, so that I couldn’t find either of them after dark; and then furnished such execrable gas that I had to hang a danger signal on the lamp post to keep teams from running into it, nights. Now I suppose your present idea is, to leave us a little more in the dark.

Don’t mind us — out our way; we possess but one vote apiece, and no rights which you are in any way bound to respect. Please take your electric light and go to — but never mind, it is not for me to suggest; you will probably find the way; and any way you can reasonably count on divine assistance if you lose your bearings.

S.L. Clemens.

“Guess whose birthday it is today?” Franklin Pierce Adams asked Beatrice Kaufman.

“Yours?” she guessed.

“No, but you’re getting warm,” he said. “It’s Shakespeare’s!”

From “Love and Freindship,” a story by the 14-year-old Jane Austen:

One evening in December, as my father, my mother, and myself were arranged in social converse round our fireside, we were on a sudden greatly astonished by hearing a violent knocking on the outward door of our rustic cot.

My father started — ‘What noise is that?’ said he. ‘It sounds like a loud rapping at the door,’ replied my mother. ‘It does indeed,’ cried I. ‘I am of your opinion,’ said my father, ‘it certainly does appear to proceed from some uncommon violence exerted against our unoffending door.’ ‘Yes,’ exclaimed I, ‘I cannot help thinking it must be somebody who knocks for admittance.’

‘That is another point,’ replied he. ‘We must not pretend to determine on what motive the person may knock — though that someone does rap at the door, I am partly convinced.’

Here, a second tremendous rap interrupted my father in his speech and somewhat alarmed my mother and me.

‘Had we better not go and see who it is?’ said she. ‘The servants are out.’ ‘I think we had,’ replied I. ‘Certainly,’ added my father, ‘by all means.’ ‘Shall we go now?’ said my mother, ‘The sooner the better,’ answered he. ‘Oh! let no time be lost,’ cried I.

A third more violent rap than ever again assaulted our ears. ‘I am certain there is somebody knocking at the door,’ said my mother. ‘I think there must,’ replied my father. ‘I fancy the servants are returned,’ said I. ‘I think I hear Mary going to the door.’ ‘I’m glad of it, cried my father, ‘for I long to know who it is.’

I was right in my conjecture; for Mary instantly entering the room informed us that a young gentleman and his servant were at the door, who had lost their way, were very cold and begged leave to warm themselves by our fire. …