- Canada’s coastline is six times as long as Australia’s.

- Rudyard Kipling invented snow golf.

- ENUMERATION = MOUNTAINEER

- Can you see your eyes move in a mirror?

- 26364 = 263 × 6/4

- “I want death to find me planting my cabbages.” — Montaigne

Literature

Higher Things

On a television show, Eddie Fisher complained to George S. Kaufman that women refused to date him because he looked so young. Kaufman considered this and replied:

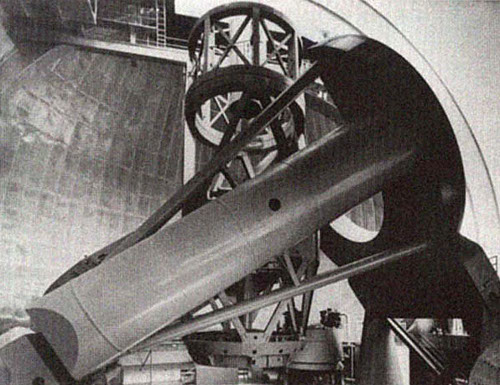

“Mr. Fisher, on Mount Wilson there is a telescope that can magnify the most distant stars up to 24 times the magnification of any previous telescope. This remarkable instrument was unsurpassed until the construction of the Mount Palomar telescope, an even more remarkable instrument of magnification. Owing to advances and improvements in optical technology, it is capable of magnifying the stars to four times the magnification and resolution of the Mount Wilson telescope. Mr. Fisher, if you could somehow put the Mount Wilson telescope inside the Mount Palomar telescope, you still wouldn’t be able to detect my interest in your problem.”

Late

Alexander Woollcott asked that his ashes be scattered at his alma mater, Hamilton College in Utica, N.Y.

Somehow they were misdirected to Colgate University, and they arrived at Hamilton with 67 cents postage due.

He once wrote, “Many of us spend half of our time wishing for things we could have if we didn’t spend half our time wishing.”

Author Relations

When Bennett Cerf published Gertrude Stein’s Geographical History of America or the Relation of Human Nature to the Human Mind in 1936, he included this “Publisher’s Note”:

This space is usually reserved for a brief description of a book’s contents. In this case, however, I must admit frankly that I do not know what Miss Stein is talking about. I do not even understand the title.

I admire Miss Stein tremendously, and I like to publish her books, although most of the time I do not know what she is driving at. That, Miss Stein tells me, is because I am dumb.

I note that one of my partners and I are characters in this latest work of Miss Stein’s. Both of us wish we knew what she was saying about us. Both of us hope too that her faithful followers will make more of this book than we were able to!

Interviewing Stein on his radio program, Cerf said, “I’m very proud to be your publisher, Miss Stein, but as I’ve always told you, I don’t understand very much of what you’re saying.”

She said, “Well, I’ve always told you, Bennett, you’re a very nice boy, but you’re rather stupid.”

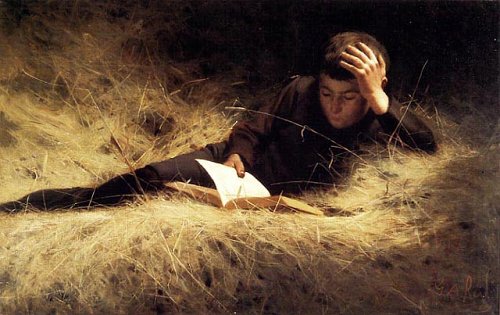

Free Study

“A man ought to read just as inclination leads him; for what he reads as a task will do him little good.” — Samuel Johnson

“Knowledge which is acquired under compulsion obtains no hold on the mind.” — Plato

“Oh! it is absurd to have a hard and fast rule about what one should read and what one shouldn’t. More than half of modern culture depends on what one shouldn’t read.” — Oscar Wilde

Authors on Authors

Oscar Wilde on Charles Dickens:

“One must have a heart of stone to read the death of Little Nell without laughing.”

Joseph Conrad on Herman Melville:

“He knows nothing of the sea. Fantastic — ridiculous.”

John Dryden on John Donne:

“Were he translated into numbers, and English, he would yet be wanting in the dignity of expression.”

Vladimir Nabokov on Joseph Conrad:

“I cannot abide Conrad’s souvenir-shop style, bottled ships and shell necklaces of romantic clichés.”

Henry James on Edgar Allan Poe:

“An enthusiasm for Poe is the mark of a decidedly primitive stage of reflection.”

H.G. Wells on George Bernard Shaw:

“An idiot child screaming in a hospital.”

Gustave Flaubert on George Sand:

“A great cow full of ink.”

Truman Capote on Jack Kerouac:

“That’s not writing, that’s typing.”

Misc

- Dorothy Parker named her dog Cliche.

- 27639 = 27 × 63 – 9

- Tikitiki cures beriberi.

- Can an object move itself?

- “The best way out is always through.” — Robert Frost

First Base

The earliest mention of baseball may be in Northanger Abbey, of all places:

… it was not very wonderful that Catherine, who had by nature nothing heroic about her, should prefer cricket, baseball, riding on horseback, and running about the country at the age of fourteen, to books.

Jane Austen wrote that passage in 1798, 41 years before Abner Doubleday supposedly invented the game in 1839. Evidence now suggests that “America’s game” evolved in England and was imported to the New World in the 18th century.

UPDATE: A reader alerts me that the town of Pittsfield, Mass., passed an ordinance in 1791 forbidding inhabitants from playing “Baseball” and certain other games near a new meeting house. This is believed to be the first written reference to baseball in North America. But a researcher at the Oxford English Dictionary tells me that the OED now has an example dating from 1748: “Now, in the winter, in a large room, they divert themselves at base-ball, a play all who are, or have been, schoolboys, are well acquainted with.” The letter writer was English, so, for the moment, England has the ball.

Salad Bar

In his 1968 novel Enderby Outside, Anthony Burgess contrived to use the word onions four times in a row:

Then, instead of expensive mouthwash, he had breathed on Hogg-Enderby, bafflingly (for no banquet would serve, because of the known redolence of onions, onions) onions. ‘Onions,’ said Hogg.

Burgess could take playfulness to excess — the first volume of the Enderby quartet got him into a bit of trouble.

Presentable

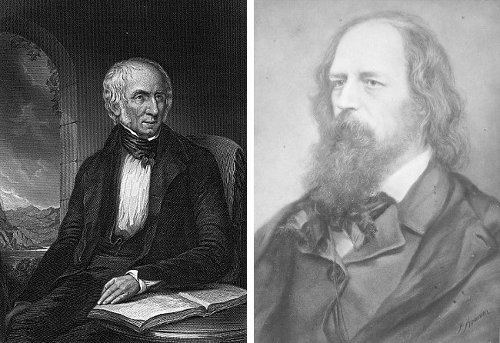

For their investiture as poet laureate, Wordsworth and Tennyson both borrowed the same suit from Samuel Rogers.

Unfortunately, Rogers was a small man. When Tennyson had trouble fitting into the suit, he asked a servant how Wordsworth had fared. “They had great difficulty in getting him into them,” the man replied.