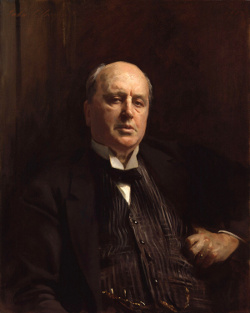

Despite his literary brilliance, Henry James was absurdly prolix in his daily life. Reportedly he once asked a waiter to “bring me … fetch me … carry me … supply me … in other words (I hope you are following me) serve–when it is cooked … scorched … grilled I should say–a large … considerable … meaty (as opposed to fatty) … chop.”

Once while motoring through England with Edith Wharton, James lost his way and hailed an old man at the side of the road. “My good man, if you’ll be good enough to come here, please; a little nearer–so. My friend, to put it to you in two words, this lady and I have just arrived here from Slough; that is to say, to be more strictly accurate, we have recently passed through Slough on our way here, having actually motored to Windsor from Rye, which was our point of departure; and the darkness having overtaken us, we should be much obliged if you would tell us where we now are in relation, say, to the High Street, which, as you of course know, leads to the Castle, after leaving on the left hand the turn down to the railway station.”

The old man looked blank. “In short, my good man,” said James, “what I want to put to you in a word is this: Supposing we have already (as I have reason to think we have) driven past the turn down to the railway station (which in that case, by the way, would probably not have been on our left hand, but on our right), where are we now in relation to–”

“Oh, please,” said Wharton, “do ask him where the King’s Road is.”

“Ah–? The King’s Road? Just so! Quite right! Can you, as a matter of fact, my good man, tell us where, in relation to our present position, the King’s Road exactly is?”

“Ye’re in it,” said the man.