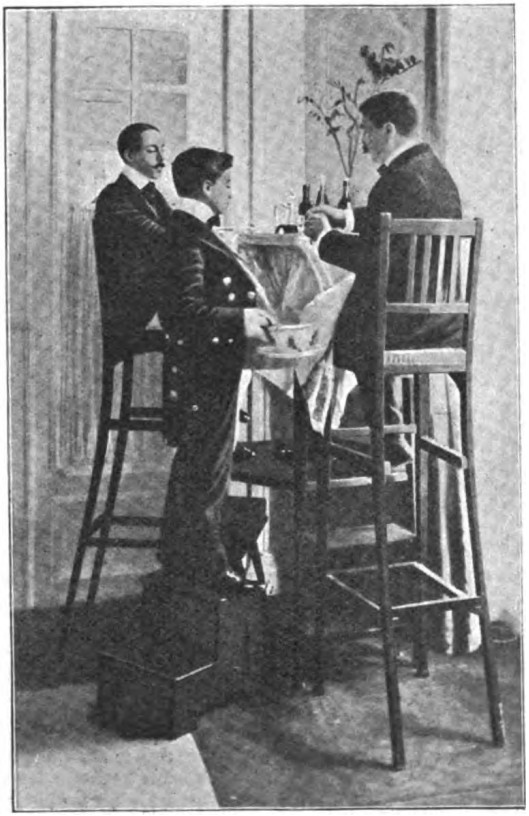

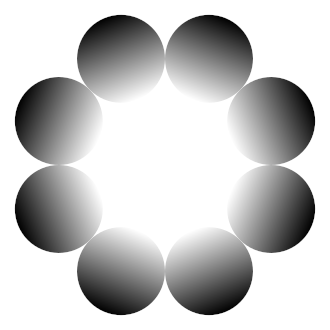

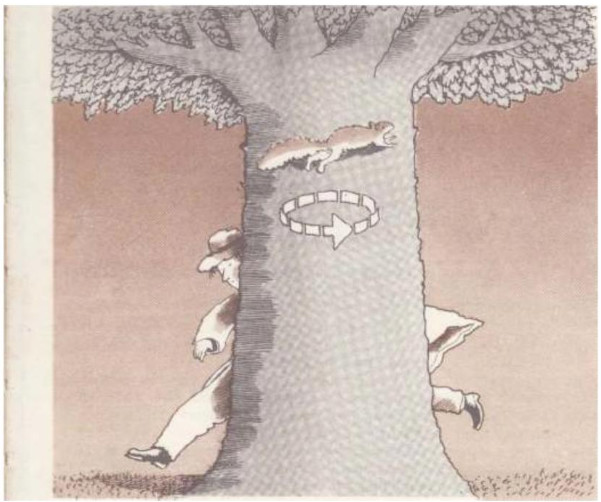

‘I had quite a bit of fun playing hide-and-seek with a squirrel,’ he said. ‘You know that little round glade with a lone birch in the centre? It was on this tree that a squirrel was hiding from me. As I emerged from a thicket, I saw its snout and two bright little eyes peeping from behind the trunk. I wanted to see the little animal, so I started circling round along the edge of the glade, mindful of keeping the distance in order not to scare it. I did four rounds, but the little cheat kept backing away from me, eyeing me suspiciously from behind the tree. Try as I did, I just could not see its back.’

‘But you have just said yourself that you circled round the tree four times,’ one of the listeners interjected.

‘Round the tree, yes, but not round the squirrel.’

‘But the squirrel was on the tree, wasn’t it?’

‘So it was.’

‘Well, that means you circled round the squirrel too.’

‘Call that circling round the squirrel when I didn’t see its back?’

‘What has its back to do with the whole thing? The squirrel was on the tree in the centre of the glade and you circled round the tree. In other words, you circled round the squirrel.’

‘Oh no, I didn’t. Let us assume that I’m circling round you and you keep turning, showing me just your face. Call that circling round you?’

‘Of course, what else can you call it?’

‘You mean I’m circling round you though I’m never behind you and never see your back?’

‘Forget the back! You’re circling round me and that’s what counts. What has the back to do with it?’

— Yakov Perelman, Mathematics Can Be Fun, 1927