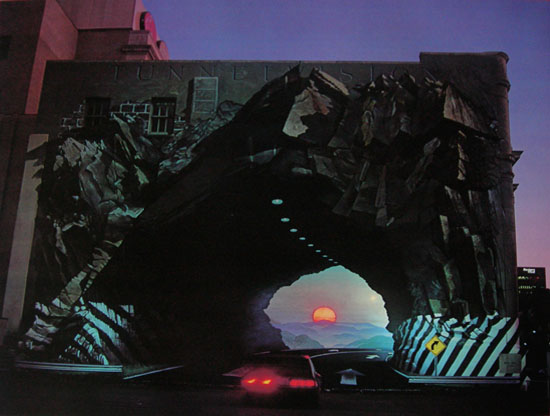

American muralist Blue Sky (formerly Warren Edward Johnson) painted Tunnelvision on the wall of the Federal Land Bank in Columbia, S.C., in 1975. “The idea for ‘Tunnelvision’ came in a dream. I woke up early in the morning and just sketched it out. I’d already seen the wall, I’d sat and studied it for hours, just waiting to see what would come before my eyes, and nothing came. And early one morning, I woke up and it was there. … That’s why I call it ‘Tunnelvision.’ Because it was a vision in a dream.” Wikipedia adds, “Rumors abound that several drunk drivers have attempted to drive into the tunnel.”

Passing trains clear a three-kilometer “tunnel of love” through the forest near Klevan, Ukraine, each spring. The trains serve a local fiberboard factory.

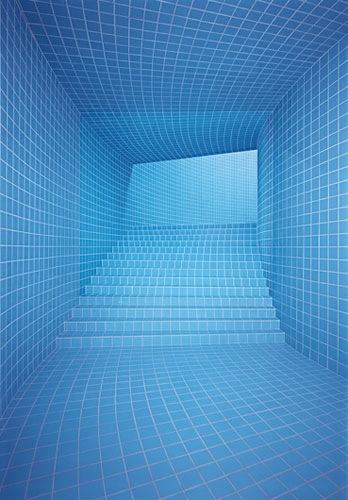

Visitors to the modern art exhibition documenta 6 in Kassel, Germany, in 1977 encountered a blue-tiled tunnel that led to the promise of daylight. They walked 14 meters into the tunnel and climbed four steps before discovering that the rest was an image painted skillfully on canvas by artist Hans Peter Reuter. “The secret of this perfect illusion lies in the combination of a realistic space with a painted surface,” writes Eckhard Hollmann and Jürgen Tesch in A Trick of the Eye (2004). “The picture alone on a white wall could never hope to have the same effect.”