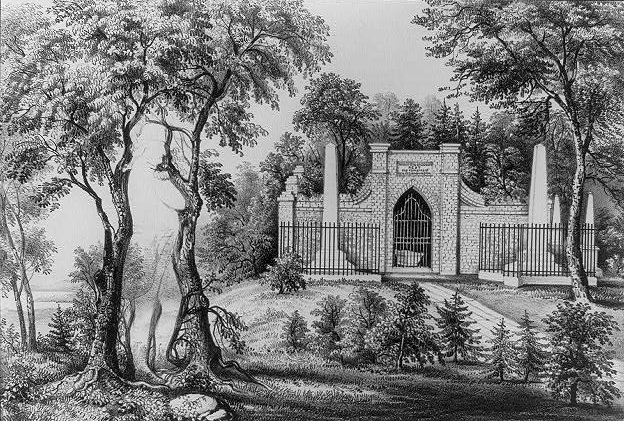

From Currier & Ives — “The Shade and Tomb of Washington.” His tomb is clear enough — where is his shade?

From Currier & Ives — “The Shade and Tomb of Washington.” His tomb is clear enough — where is his shade?

On Sept. 21, 1956, Navy pilot Tom Attridge put his supersonic F11F Tiger into a shallow dive and test-fired two bursts from its 20mm cannon. Unfortunately, the jet was traveling so fast that it overtook its own rounds. One struck the engine, which failed on the way back to the airfield. Attridge crash-landed, losing a wing and a stabilizer but getting away safely. His Tiger had become the first jet aircraft to shoot itself down.

A puzzle sent to me by a Caltech grad student: A man is walking his dog on the beach. Each time he blows a whistle, the dog doubles its speed. If the dog starts at 2 meters per second, how many whistles does it hear? Answer: Fifteen — when the dog exceeds the speed of sound, it catches up with the earlier whistles.

(Thanks, John and Srivatsan.)

What is this? Most people see a mass of black blobs and then gradually recognize a photograph of a Dalmatian.

“What is interesting is that the outline shape on the picture surface that is experienced as resembling that of a dog is not seen as an outline shape at all unless the dog is seen in the figure,” writes University of British Columbia philosopher Dominic McIver Lopes. There’s no dog-shaped outline to notice; the contour of the dog’s body is invisible. To see the contour we must first see the dog … but how do we see the dog without the contour?

[Theodore] Dreiser said that when he was living in New York, on West Fifty-seventh Street, John Cowper Powys came occasionally to dinner. At that time Powys was living in this country, in a little town about thirty miles up the Hudson, and he usually left Dreiser’s place fairly early to catch a train to take him home. One evening, after a rather long after-dinner conversation, Powys looked at his watch and said hurriedly that he had no idea it was so late, and he would have to go at once or miss his train. Dreiser helped him on with his overcoat, and Powys, on his way to the door, said, ‘ I’ll appear before you, right here, later this evening. You’ll see me.’

‘Are you going to turn yourself into a ghost, or have you a key to the door?’ Dreiser laughed when he asked that question, for he did not believe for an instant that Powys meant to be taken seriously.

‘I don’t know,’ said Powys. ‘ I may return as a spirit or in some other astral form.’

Dreiser said that there had been no discussion whatever during the evening, of spirits, ghosts or visions. The talk had been mainly about American publishers and their methods. He said that he gave no further thought to Powys’s promise to reappear, but he sat up reading for about two hours, all alone. Then he looked up from his book and saw Powys standing in the doorway between the entrance hall and the living room. The apparation had Powys’s features, his tall stature, loose tweed garments and general appearance, but a pale white glow shone from the figure. Dreiser rose at once, and strode towards the ghost, or whatever it was, saying, ‘Well, you’ve kept your word, John. You’re here. Come on in and tell me how you did it.’ The apparation did not reply, and it vanished when Dreiser was within three feet of it.

As soon as he had recovered somewhat from his astonishment Dreiser picked up the telephone and called John Cowper Powy’s house in the country. Powys came to the phone, and Dreiser recognized his voice. After he had heard the story of the apparation, Powys said, ‘I told you I’d be there, and you oughtn’t to be surprised.’ Dreiser told me that he was never able to get any explanation from Powys, who refused to discuss the matter from any standpoint.

— W.E. Woodward, The Gift of Life, 1947

On Sept. 9, 1942, a lookout on Mount Emily in Oregon’s Siskiyou National Forest reported a plume of smoke near the town of Brookings. The Forest Service contained the fire easily, but investigators turned up something odd at the site: fragments of an incendiary bomb of Japanese origin.

It turned out that a Japanese submarine had surfaced off the Oregon/California border and 31-year-old navy officer Nobuo Fujita had piloted a seaplane into the forest, hoping to start a fire that would divert U.S. military resources from the Pacific. Recent rains had wet the forest, so the plan failed, but it marked the first time the continental United States had been bombed by enemy aircraft.

Fujita returned safely to Japan, where he opened a hardware store after the war, and he became an agent of amity with the United States. In 1962 he accepted an invitation to return to Oregon, where he donated his family’s samurai sword to Brookings, and he invited three local students to visit Japan in 1985. The city made him an honorary citizen shortly before his death in 1997, and his daughter spread his ashes at the site of the bombing.

‘All the world loves a lover.’ But in Venezuela, they do something about it. T.R. Lahey, in the Catholic periodical, Ave Maria, is responsible for the statement that the postal authorities there allow love letters to go through the mails at half price! But there is a condition. The letters must be mailed in bright-colored envelopes (pansy-blue for loving thoughts, and pink cloud effects; there would be a place for yellow and green to express the feelings of envious suitors and jealous lovers). These bright tints are intended to help the postal clerks and postmen to recognize the nature of the missives; but what a temptation to the carriers to open the letters and cull precious thoughts and phrases!

— The Lutheran, Nov. 6, 1940

Reiss records the death of a woman who was hastily buried while her husband was away, and on his return he ordered exhumation of her body, and on opening the coffin a child’s cry was heard. The infant had evidently been born postmortem. It lived long afterward under the name of ‘Fils de la terre.’ Willoughby mentions the curious instance in which rumbling was heard from the coffin of a woman during her hasty burial. One of her neighbors returned to the grave, applied her ear to the ground, and was sure she heard a sighing noise. A soldier with her affirmed her tale, and together they went to a clergyman and a justice, begging that the grave be opened. When the coffin was opened it was found that a child had been born, which had descended to her knees. In Derbyshire, to this day, may be seen on the parish register: ‘April ye 20, 1650, was buried Emme, the wife of Thomas Toplace, who was found delivered of a child after she had lain two hours in the grave.’

— George Milbry Gould and Walter Lytle Pyle, Anomalies and Curiosities of Medicine, 1896

From an account by Spanish priest Pedro Simón of an expedition led by Luis Alonso de Lugo against the Tairona Indians of Colombia, 1535:

At dawn, as they lay hidden in the cornfields which surrounded the village, awaiting the moment to attack, they heard an ass bray. They knew that the Indians did not possess such animals, and did not believe that an ass could have climbed the high crags which barred the way from the coast. … When the place had been pacified and looted, they enquired about the ass … The Indians said that it had come in a ship, which had been wrecked on the coast. … They had killed those of the ship’s company who got ashore, but had kept the ass, and had carried it up into the mountains, trussed with ropes and slung between two poles, along with all the other loot they found in the ship. … So our soldiers, deeming it inappropriate and contrary to native custom that such articles should be in the hands of Indians, collected them all up, along with everything else that took their fancy, including the ass, and took it back to the coast. But the trails were rough, more suited to cats than men, and the descent was as hard as the ascent had been, so they made the Indians carry the donkey down just as they had brought it up; and very useful it turned out to be. Surely, as the first of its race to penetrate those mountains, it deserved to be numbered among the conquistadores. It served in other entradas later, and finally in the expedition which Hernando de Quesada, brother and deputy of Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada the discoverer, led in search of El Dorado. It was ridden by Fray Vicente Requejada of the Order of Saint Augustine. … The ass served the friar well until, on the return march, they all ran out of food and, in the extremities of hunger, killed it for food. They left not a scrap of it. They collected its blood, made sausages of its guts, and even devoured its hide, well boiled. It had served them well in life, and served them better still in death, by its timely rescue from starvation; a salutary reminder of the hardships which in those days were the daily lot of discoverers.

See An Ass Cast Away and Hoof Positive.

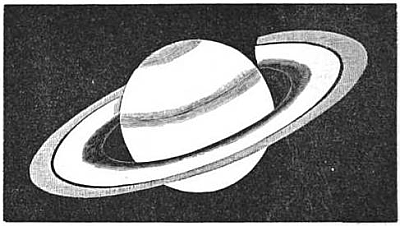

An astronomical oddity, from the Sidereal Messenger, June 1890:

On the evening of April 25th, 1889, at about 8:30 p.m., I was examining Saturn with a power of about 180 on a 4 1/8-inch achromatic by Brashear, when, much to my surprise, I found the shadow of the globe on the rings curved the wrong way, i.e. from the globe, as shown in the following drawing. Thinking my eyes might be deceiving me I called my wife, and without telling her what I had seen, requested her to describe the shape of the shadow. She described the shadow as having its right hand edge curved away from the planet.

I wrote to Professor Comstock of the Washburn Observatory about it, and was informed by him that while my observation of Saturn was unusual, it was far from being unprecedented; that the same appearance was observed in 1875 with the 26-inch achromatic at Washington, and that Webb, in ‘Celestial Objects for Common Telescopes,’ says: ‘The outline of this shadow has often been found curved the wrong way for its perspective.’ Professor Comstock also adds, ‘I do not know that any satisfactory explanation for this anomaly has ever been given.’

William Corliss notes a flurry of similar observations between 1886 and 1914. I think this must have been explained by now, but I haven’t been able to find a source.

(Jenks, Aldro; “On the Reversed Curvature of the Shadow on Saturn’s Rings,” Sidereal Messenger, 9:255, 1890.)

In 1946 an American doctor named Jones was tried in Ohio for performing six illegal abortions (State v. Jones, 80 Ohio App. 269). In one of the six cases, the only evidence was the testimony of the woman herself, Jacquelin Harris. But under Ohio law, the recipient of an abortion was an accomplice to the crime, and the unsupported testimony of an accomplice was suspect and insufficient for a conviction.

This means trouble:

“This puts the jury in a position of returning a self-annulling verdict,” writes Peter Suber in The Paradox of Self-Amendment. “If they find Jones guilty, then they must find that Harris was his accomplice, then they must find her evidence against Jones insufficient, then they must acquit Jones. But if they find Jones innocent, then they must (at least may) find Harris’ evidence legally sufficient, then they must (at least may) convict Jones.”

Jones was found guilty, ironically because, as an accused party, he was presumed innocent, and so the witness was presumed not to be an accomplice. “This led to the remarkable situation that the testimony was admissible and could lead to a conviction,” writes Michael Clark in Paradoxes From A to Z, “notwithstanding the fact that the conviction undermined the probative value of the testimony.”

See Turnabout.