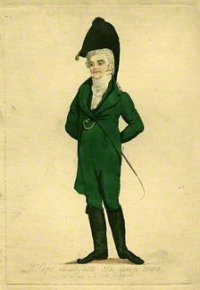

A dwarf named Richbourg, who was only sixty centimetres (23 1-2 inches) high, has just died in the Rue du Four, St. Germain, Paris, aged 90. He was, when young, in the service of the Duchess d’Orleans, mother of King Louis Philippe. After the first revolution broke out he was employed to convey despatches abroad, and, for that purpose, was dressed as a baby, the despatches being concealed in his cap, and a nurse being made to carry him. For the last twenty-five years he has lived in the Rue du Four, and during all that time never went out. He had a great repugnance to strangers, and was alarmed when he heard the voice of one; but in his own family he was very lively and cheerful. The Orleans family allowed him a pension of 8000 francs.

— Ballou’s Dollar Monthly Magazine, February 1859