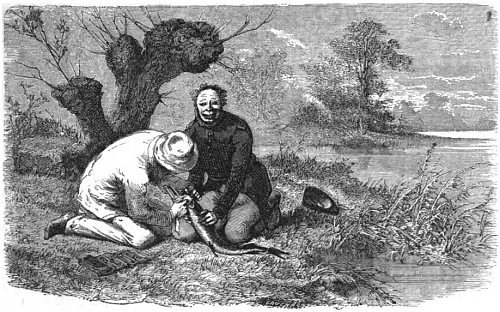

When I lived at Durham, I was walking one evening in a park belonging to the Earl of Stamford, along the bank of a lake where fishes abounded. My attention was turned towards a fine jack of about 6 lbs., which, seeing me, darted into the middle of the water. In its flight it struck its head against the stump of a post, fractured its skull, and wounded a part of the optic nerve. The animal gave signs of ungovernable pain, plunged to the bottom of the water, burying its head in the mud, and turning with such rapidity that I lost it for a moment; then it returned to the top, and threw itself clean out of the water on to the bank. I examined the fish, and found that a small part of the brain had gone out through the fracture of the cranium.

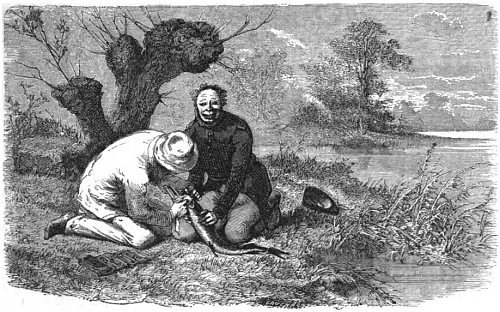

I carefully replaced the shattered brain, and, with a small silver tooth-pick, raised the depressed parts of the skull. The fish was very quiet during the operation; then I replaced it in the pond. It seemed at first relieved, but after some minutes it threw itself about, plunged here and there, and at last threw itself once more out of the water. It continued thus to act many times following. I called the keeper, and, with his assistance, applied a bandage to the fracture. This done, we threw the fish into the water, and left him to his fate. The next morning, when I appeared on the bank, the pike came to me near where I sat, and put his head near my feet! I thought the act extraordinary, but taking up the fish, without any resistance on its part, I examined the head, and found that it was going on well. I then walked along the banks for some time; the fish did not cease to swim after me, turning when I turned; but as it was blind on the side where it was wounded, it appeared always agitated when the injured eye was turned toward the bank. On this, I changed the direction of my movements. The next day I brought some young friends to see this fish, and the pike swam towards me as before. Little by little he became so tame that he came when I whistled, and ate from my hand. With other people, on the contrary, it was as gloomy and fierce as it always had been.

— “Dr. Warwick,” anecdote read before the Literary and Philosophical Society of Liverpool, 1850, quoted in Ernest Menault, The Intelligence of Animals, 1869