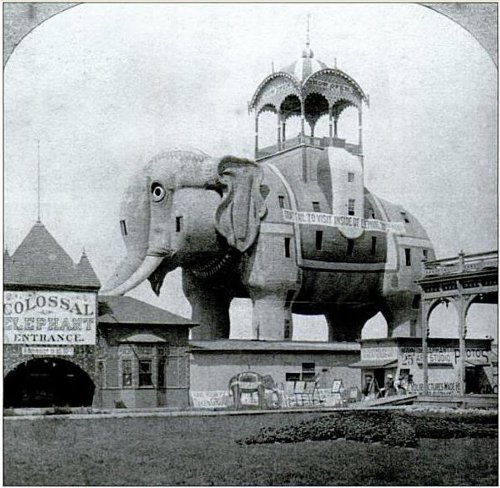

Between 1884 and 1896, visitors to Coney Island could stay in an elephant. Each leg of the tin-skinned wooden behemoth was 60 feet long; its ears were 40 feet wide; and the enormous trunk measured 72 feet. The forelegs housed a diorama and a cigar store, and the hind legs contained staircases leading to 31 hotel rooms above — advertised entertainingly as “a main hall head room, 2 side body rooms, 2 thigh rooms, 2 shoulder rooms, 2 cheek rooms, 1 throat room, 1 stomach room, 4 hoof rooms, 6 leg rooms, 2 side rooms, 2 hip rooms, 1 through room from which the Elephant is feeding.” (Presumably this last carried a discount.)

The hotel idea didn’t work out, and in the end the building served mostly as a concert hall and amusement bazaar, with novelty stalls, a gallery, and a museum. Visitors could use telescopes to peer out of the monster’s glass eyes, and it was said that the mists of Niagara could be seen from the howdah on its back, which teetered at a height of 175 feet.

The contractor that built the colossus said that it would last half a century, but within 12 years it had been abandoned and burned to the ground. All that remained was part of a foreleg.