If you are somewhere else, you are not here.

You are not in Rome; you are somewhere else.

Therefore you are not here.

If you are somewhere else, you are not here.

You are not in Rome; you are somewhere else.

Therefore you are not here.

When World War I broke out in August 1914, Germany enlisted a large ocean liner, the Cap Trafalgar, to attack British merchant ships around Cape Horn. While at a supply base on Trinidade, it was surprised by the HMS Carmania, a British liner that had been similarly pressed into service by the British navy.

The two enormous ships squared off and fought a murderous sea battle. In the end the Cap Trafalgar sank, and the Carmania limped away to a Brazilian port.

An observer might still have wondered which side won — by an ironic coincidence, the Cap Trafalgar had been disguised as the Carmania and the Carmania as the Cap Trafalgar.

At 5 p.m. on Dec. 2, 1919, Canadian theater magnate Ambrose Small met with a lawyer in his Toronto office. The lawyer departed at 5:30 p.m. Between 5:30 and 6:00, Small vanished.

No one saw him leave the office, and no body was ever found. The disappearance seemed senseless. Small was a self-made millionaire; no money was missing, there was no evidence of kidnapping, and no ransom note was ever received.

Curiously, writer Ambrose Bierce had disappeared in Mexico six years earlier. Charles Fort wondered, “Was somebody collecting Ambroses?”

Jazz pianist Billy Tipton was biologically female. She lived as a man from age 19 to her death at 74, when the truth was discovered.

Born in 1914, Dorothy Tipton developed an early love of jazz, but sexism in the music industry and the straitened economy of the Depression made it impossible to find work. In 1933 she donned trousers and her father’s nickname and began playing in Oklahoma bars.

By the 1940s she was touring the country, and in the 1950s the Billy Tipton Trio released two albums for Tops Records and performed with Duke Ellington, Patti Page, and Rosemary Clooney. Arthritis finally forced Billy’s retirement in the 1970s.

Throughout all this Tipton had relationships with at least five women, including nightclub dancer Kitty Kelly, with whom she raised three adopted sons. She bound her chest, ostensibly to protect ribs fractured in an auto accident, and she always locked the bathroom door. Son William learned of his father’s sex only when a paramedic working on the dying Tipton asked, “Son, did your father have a sex change?”

Why keep a secret for 55 years? Tipton left no account of her reasons, and perhaps it’s none of our business. “I can’t say that passion wasn’t there with Billy, because it was,” said former lover Betty Cox, who insisted she never suspected Billy’s sex even during intimacy. “Now, 40 or 50 years later, you see these cross-dressers all the time on TV. You can certainly tell. Even on TV. I can look at a person and say, ‘Gee, that’s obviously a woman.’ Why couldn’t I then?”

A few miles to the northeast of Woodstock lies the village of Saugerties, and just before entering it, Routes 212 and 32 come together. We do not know who first gave this juncture the name of Fahrenheit Corners, but as a large IBM plant is in the vicinity, we may reasonably suspect one of its more whimsical employees.

— Journal of Recreational Mathematics, October 1981

The California Court of Appeal faced a curious philosophical question in 1989: Do you become a year older on your birthday, or on the preceding day?

Paul Johnson had committed a robbery in San Francisco on Aug. 12, 1988, one day before his 18th birthday. The prosecution had charged him as an adult, arguing that “A person is in existence on the day of his birth. On the first anniversary he or she has lived one year and one day.”

Is that so? The appeals court didn’t buy it — Justice William Channell overruled the prior decisions and had Johnson tried as a juvenile.

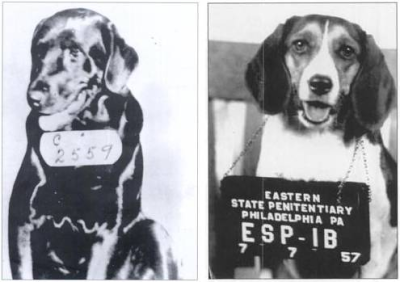

Philadelphia’s Eastern State Penitentiary got an unusual inmate in 1924: “Pep the cat-murdering dog,” a black Labrador retriever who was allegedly incarcerated for killing the first lady’s favorite pet. In truth Pep was donated to the prison by governor Gifford Pinchot to improve morale; he was transferred to nearby Graterford Penitentiary in 1929.

Pep’s example was followed by Lady, a beagle who belonged to the captain of the prison’s guards. She posed for the second picture in 1957.

In American Notes, Dickens recalled that one inmate at Eastern State kept a rabbit in his cell; others kept birds and cats. And the prison was later home to Al Capone, who had some unusual quarters of his own.

Albert Herpin, born in France in 1862 and for fifteen years a hostler in the employ of Freeholder Walter Phares of this city, declares that he has not slept a wink during the past ten years. Notwithstanding this, he is in perfect health, and does not seem to suffer any discomfort from his remarkable condition. He goes to bed regularly, but says he never closes his eyes, or at least never for an instant loses consciousness of all going on about him. In the morning he arises refreshed and ready for another day’s work among the horses. He declares the change of position and the darkness of the room seem to give him all the rest he desires.

— “Hasn’t Slept in Ten Years,” New York Times, Feb. 29, 1904

The following anecdote appears so marvellous, that we can scarcely expect it to obtain general belief; but it has been transmitted to us by a most respectable correspondent; a correspondent who is far from being credulous himself, and who has no interest in deceiving others:–‘The other day, a horse belonging to Mr. Thomas Johnstone, tenant on the estate of Major Culton of Auchenabony, having lost a shoe, and probably feeling his foot somewhat uneasy from the want of it, left the field where he was grazing, and went to a smithy about a mile distant, where he used to be shod. On arriving, he was observed to pause a few minutes, as if in expectation that the owner of the house would come out, and introduce him in due form; but finding nobody in attendance, he walked in, placed himself in the corner where he used to stand during the operation of shoeing; and on the smith’s coming in, he instantly made known his errand by holding up the shoeless foot. Soon after, the owner of the horse having missed him, came to the smithy in the course of his search, and to his no small surprise, found THE SMITH ENGAGED IN PUTTING ON A SHOE!’

— “Dumfries paper,” quoted in The Kaleidoscope, July 10, 1821

On June 3, 1872, retired Navy captain George Colvocoresses bought a ticket for the boat from Bridgeport, Conn., to New York, where he had an appointment the next day with an insurance agent. He put a leather valise in his stateroom and dined in the restaurant, where he was observed to keep a small morocco traveling bag in his lap. At 10:30 a local druggist sold him some writing paper and envelopes and indicated the best route back to the boat. Just as the boat was putting off, a pistol shot was heard, and a policeman found Colvocoresses dying in the street.

His clothing was unbuttoned, and his shirt was on fire at the point where the bullet had entered, about 6 inches below the left breast. His possessions were near him except for the traveling bag, which was later found on a Naugatuck wharf, cut open with a dull knife. Diagonally across the street from the body was a large old-fashioned horse pistol. On the following day, percussion caps, a bullet, and a powder horn were found about 60 feet from where the body had been discovered.

Was this murder or suicide? Colvocoresses had recently increased the insurance on his life to $198,500, and it was claimed that the pistol’s hammer fitted an indentation in his bag. But a physician testified that it would be impossible for a man to shoot himself and then throw the pistol across the street, and the captain was healthy, on good terms with his family, and had adequate means.

After a long fight the insurance companies agreed to pay 50 cents on the dollar. That’s all we know.