An optical illusion. The gray bars on the left appear lighter than those on the right, but in fact they’re the same color.

An optical illusion. The gray bars on the left appear lighter than those on the right, but in fact they’re the same color.

The taking of the United States census, now nearly completed, has brought to light some curious specimens of given names. A man in Illinois has five children, who have been christened Imprimis, Finis, Appendix, Addendum, and Erratum. In Smythe County, Virginia, a Mr. Elmadoras Sprinkle has called his two sons Myrtle Ellmore and Onyx Curwen, and his six daughters Memphis Tappan, Empress Vandalia, Tatnia Zain, Okeno Molette, Og Wilt, and Wintosse Emmah. The great number of persons surnamed Sprinkle in that county is given as the excuse for these extraordinary names.

— Notes and Queries, Dec. 10, 1870

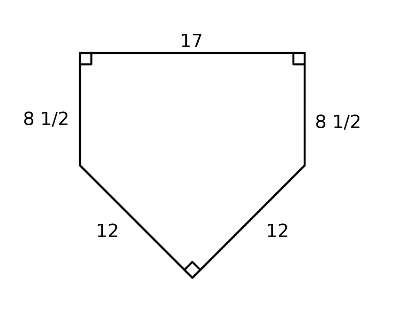

Merrimack College mathematician Michael J. Bradley was coaching his son’s Little League team in 1996 when he noticed something odd in the rulebook:

Home base shall be marked by a five-sided slab of whitened rubber. It shall be a 12-inch square with two of the corners filled in so that one edge is 17 inches long, two are 8 1/2 inches and two are 12 inches.

That’s impossible. “The figure implies the existence of a right isosceles triangle with sides 12, 12 and 17. But (12, 12, 17) is not (quite) a Pythagorean triple: 122 + 122 = 288; 172 = 289.”

“Thus, these specifications seem to give new meaning to a ‘Field of Dreams.'”

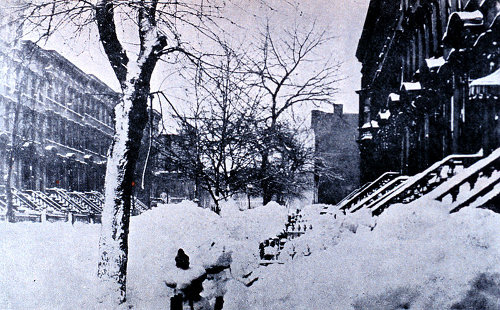

New England got unexpectedly clobbered in March 1888 when 40 inches of snow fell in a day and a half. Businesses were closed and streetcars abandoned as screaming winds whipped the drifts into house-devouring hills as deep as 50 feet. Thirty trains were paralyzed near New York City, their passengers taken in by nearby residents, and the city’s fire engines lay mired in the streets, unable to respond to calls. “Despatches between Boston and New York were sent by way of London” due to downed lines, reported the Albany Cultivator & Country Gentlemen, and “for two hours on Tuesday people crossed the East river on an ice floe brought up by the tide.”

The forecast had been “clearing and colder, preceded by light snow.”

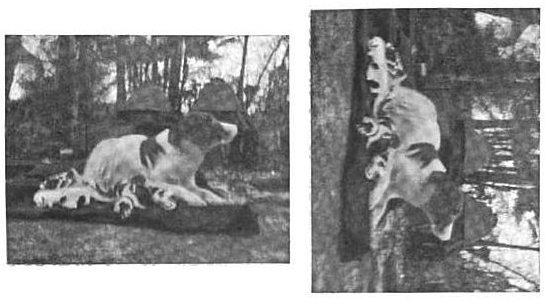

A Yorkshire police constable sent this image to the Strand in 1907: “This photograph of dog and puppies was about to be thrown away as a failure, when on turning the picture sideways it was found that the dog’s body has the appearance of a man’s head”:

This undated photo seems to reveal the image of a bearded Jesus:

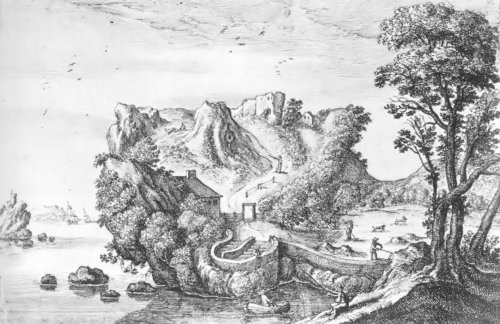

And Bohemian artist Wenzel Hollar etched Landschafts-Kopf in the 17th century:

Is it a portrait or a landscape?

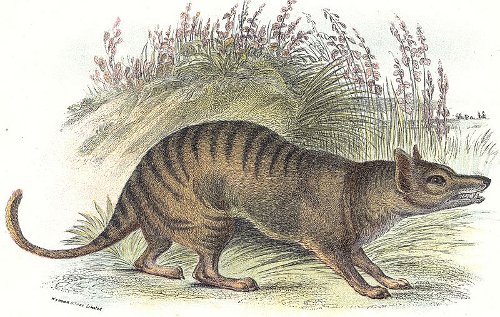

In 1810, a mysterious creature began killing sheep in northern England. Between May and September it defied the entire county of Cumberland, killing up to eight sheep a night despite being hunted nearly continuously. The “girt dog” never attacked the same flock on successive nights; it ignored poisoned meat left for it and led frustrated farmers on fruitless chases of 20 miles and more, occasionally turning to savage the forelegs of the pursuing dogs but never uttering a sound.

Finally, in September, the creature was run to ground near the Ehen River and shot. In four months it had killed more than 300 sheep. The carcass, which weighed 112 pounds, was stuffed and set up in a museum in Keswick, though it’s since been lost. Its description — a tawny dog with a tiger’s stripes — curiously matches that of the thylacine (above), a wolflike marsupial native to Tasmania. Possibly an exotic predator had escaped from a traveling menagerie and found itself peculiarly adapted to Cumberland farmland. We’ll never know.

A paper received from Natal Africa contains an article by Rev. Josiah Tyler on the similarity of Jewish and Zulu customs. Among them we mention several: The feast of first fruits, rejection of swine’s flesh, right of circumcision, the slayer of the king not allowed to live, Zulu girls go upon the mountains and mourn days and nights, saying ‘Hoi! Hoi!’ like Jepthah’s daughter, traditions of the universal deluge, and of the passage of Red Sea; great men have servants to pour water on their hands; the throwing stones into a pile; blood sprinkled on houses. The authors’ belief is that the Zulus were cradled in the land of the Bible. Certain customs are mentioned which may be ascribed to the primitive tribal organism. These are as follows: Marriages commonly among their own tribe; uncle called father, nephew a son, niece a daughter; inheritance descends from father to eldest son. If there are no sons it goes to the paternal uncle. A surmise has been advanced by some that the relics of the Queen of Sheba’s palace may be found in certain ancient ruins described by Peterman, Baines and others, and the Ophir of scripture has been located at Sofala, an African port.

— The American Antiquarian, January 1885

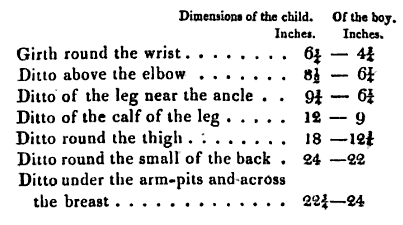

Born to an Enfield miller in February 1779, Thomas Hills Everitt began to grow apace after six weeks, and it soon became clear that he was a young giant. When he reached 9 months and 2 weeks a local surgeon compared his dimensions to those of a 7-year-old boy:

His height at that point was 3 foot 1, and his weight was estimated at 9 stone.

Eventually his parents moved to London and began to exhibit him to the public; he was said to be well proportioned, with fine hair, pure skin, an expressive face, and a good temper, and he “subsisted entirely on the breast.” The surgeon hoped he might live to some enormous maturity, but he died in 1780, at about 18 months.

This is rather romantically obscure: On June 18, 1829, a stranger arrived on the American side of Niagara Falls and took a room at a local hotel. His name was Francis Abbott, and after viewing the falls he declared himself so enchanted that he extended his stay from a few days to a week, and then to a month. Eventually he took up residence in an old cottage on Goat Island, where he lived alone contemplating the falls for some 20 months. Occasionally he could be seen walking precariously along a single beam of timber that projected over the flood at the Terrapin Bridge. On June 10, 1831, he disappeared while bathing in the water, and on June 21 his body was discovered downstream at Fort Niagara.

Abbott had shunned society increasingly, but the villagers who had interacted with him could assemble a picture. He was an English gentleman of a finished education, skilled in music and drawing, and had visited Egypt, Palestine, Turkey, Greece, Italy, Spain, Portugal, and France. He wrote in Latin but destroyed his compositions. When the villagers investigated his hut they found his dog at the door and his cat on the bed; his guitar, his violin, flutes, and music books were scattered about, but his portfolio and the leaves of a large book were blank.

“What, it will be asked, could have broken up and destroyed such a mind as Francis Abbott’s?” asked the New York Mirror. “What could have driven him from the society he was so well qualified to adorn — and what transform him, noble in person and in intellect, into an isolated anchorite, shunning the association of his fellow-men? The history of his misfortunes is not known, and the cause of his unhappiness and seclusion will, undoubtedly, to us be ever a mystery.”

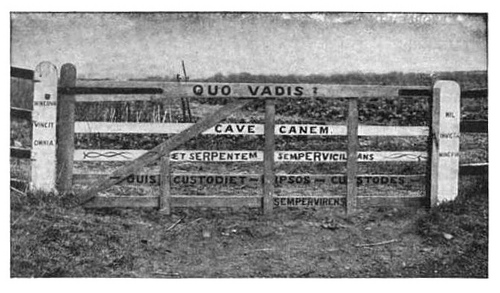

Being on a main road in Ashwell, Hertfordshire, this gate, with its peculiar inscriptions, naturally causes much comment. It stands on a field belonging to Mr. C.H.P. Walkden, whose orchard has suffered severe depredations, and shows his philosophical endeavour to cope with the evildoers.

— Strand, July 1908