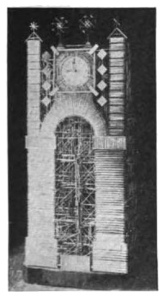

“There is probably no more unsuitable material with which to build a clock than straw. Yet this has been accomplished recently by a German shoemaker, who, during his leisure time, has made the ingenious piece of mechanism illustrated herewith. One would think that at least certain of the movable parts, or the springs, would be fashioned of some hard material such as bone, wood, or metal, yet nothing else was employed but straw. The figures, hands, dial, pendulums, chain, weight, gears, and the whole skeleton consist of this breakable stuff. By pressing a button, which comes out automatically on one side, the clockwork is wound up, and runs for five hours. There are eight pendulums, which allow regulation of speed. The chain is fourteen inches long and without end, like that of a bicycle. The diameter of the dial is eight inches. There were probably some thousands of stalks used in the work, each being three and four fold, to give more strength, one sliding within the other. No less than fifteen years was required to complete this wonderful clock.”

— Strand, July 1908