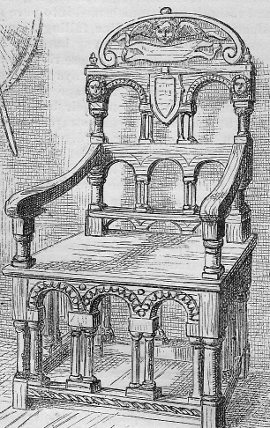

When the Golden Hind was broken up in 1662, its timbers were fashioned into a chair that still resides in the Bodleian Library at Oxford. Abraham Cowley wrote an ode, “Sitting and Drinking in the Chair, Made Out of the Reliques of Sir Francis Drake’s Ship”:

As well upon a staff may Witches ride

Their fancy’d Journies in the Ayr,

As I sail round the Ocean in this Chair:

‘Tis true; but yet this Chair which here you see,

For all its quiet now, and gravitie,

Has wandred, and has travailed more,

Than ever Beast, or Fish, or Bird, or ever Tree before.

In every Ayr, and every Sea’t has been,

‘T has compas’d all the Earth, and all the Heavens ‘t has seen.

Let not the Pope’s it self with this compare,

This is the only Universal Chair.

“While armchair travelers dream of going places,” wrote Anne Tyler, “traveling armchairs dream of staying put.”