In 1871, a Norwegian seal hunter discovered a wooden hut on Novaya Zemlya in the Arctic Ocean. In it he found clothing, cooking pots, a tool chest, a clock, a flute, a cooking tripod, and several pictures.

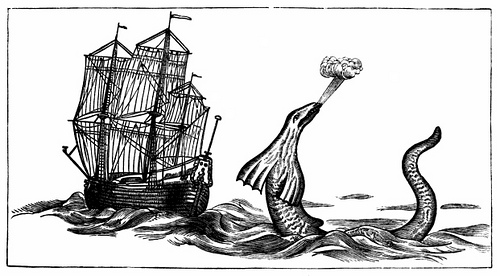

It was the lodge of Willem Barentsz, who had passed the winter there in 1597 while seeking a northern route to China. Barentsz had died on the return journey, and the hut had stood for 270 years, awaiting rediscovery.

According to an 1877 report, later investigations recovered Barentsz’s quill pen, a translation of a work on seamanship printed in 1580, “some candles nearly 280 years old, but still capable of giving light” — and “the Amsterdam flag, the first European colour that passed a winter in the Arctic region.”