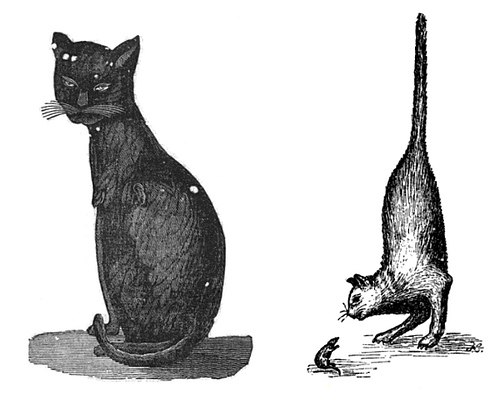

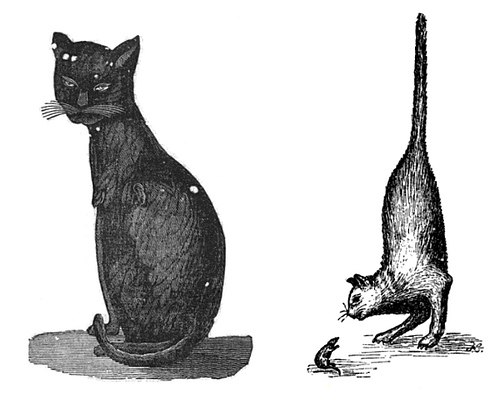

The cat on the left appeared in Nathaniel Hawthorne’s American Magazine of Useful and Entertaining Knowledge in October 1836. It’s difficult to tell from the drawing, but I think she’s missing her left front and right rear legs. “She was active, and would leap on a table, to the height three or four feet. Her gait is odd, as might be supposed, and often she leaps like a frog. … She frequently sits in the posture as given in the annexed drawing, especially when expecting to receive food; and her appearance very singular and rather ludicrous. Though destitute of claws, she is a good mouse-catcher. The tail is usually extended, and then she resembles somewhat that singular animal, the kangaroo.”

The other was featured in Arthur’s Home Magazine in July 1891, “a most cheerful, healthy, engaging little creature” whose “fashion of walking was queer, but lively.” She belonged to F.C. Hill, a professor at Princeton, who returned from a two-week trip in spring 1877 to find her dead. “Poor kitty was well and happy while I was with her,” he wrote. “I really think she pined and died as much from loneliness as anything else.” Her skeleton was displayed in the museum at Princeton College, “so that pussy remains as serviceable after death as it was her warm will to be in life.”