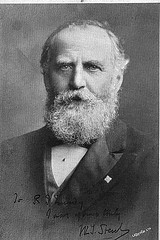

As a writer, W.T. Stead may have been too prescient.

In 1886 he published an article about the sinking of an ocean liner and the consequent loss of life, warning, “This is exactly what might take place and will take place if liners are sent to sea short of boats.”

Six years later he wrote a novel, From the Old World to the New, in which a ship collides with an iceberg in the North Atlantic and sinks; the survivors are picked up by the Majestic, a ship of the White Star Line.

An outspoken newspaper editor, Stead himself embarked for the New World in April 1912 when President Taft invited him to address a peace conference at Carnegie Hall.

Alas, he never arrived — he had booked his passage on the RMS Titanic.