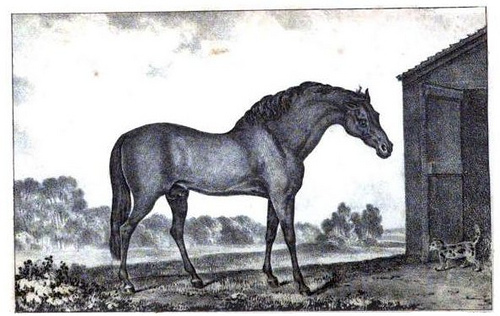

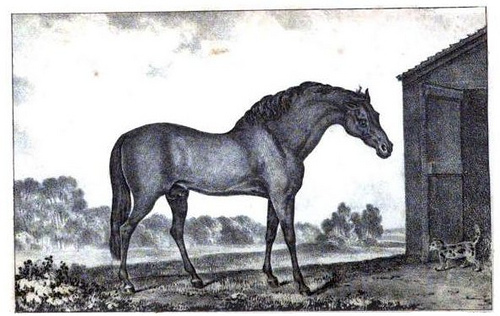

In the 1740s, workers at a stable near Cambridge noticed that a cat had taken a peculiar fancy to one of the horses there. She was always near him, they found, sitting on his back or nestling nearby in the manger.

Her attachment proved so great that when the stallion died in 1754 “she sat upon him after he was dead in the building erected for him, and followed him to the place where he was buried under a gateway near the running stable; sat upon him there till he was buried, then went away, and never was seen again, till found dead in the hayloft” — apparently of grief.

The cat’s name is not recorded, but she certainly could pick horses: The stallion was the Godolphin Arabian, now revered as the founder of modern thoroughbred racing stock. His direct descendants include both Seabiscuit and Man o’ War.