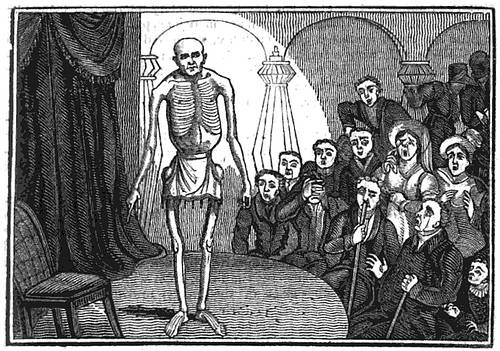

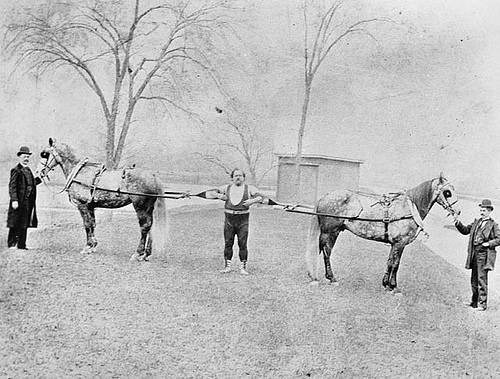

Feats of Canadian strongman Louis Cyr (1863-1912), “the strongest man who ever lived”:

- In 1881 he lifted a horse weighing at least 1500 pounds.

- In 1886 he lifted a 218-pound barbell with one hand and raised 2,371 pounds on his back.

- In 1895 he raised a platform that held 18 men.

- In 1889 he shouldered a 433-pound barrel of cement with one arm and lifted 552.5 pounds clear of the floor with a single finger.

- In 1891 he resisted the pull of four draft horses even as grooms drove them apart with whips.

Where did he get these gifts? “The mother of Louis Cyr … could easily shoulder a barrel of flour and carry it up two or three flights of stairs.” (Josephine Beiderhase, American Gymnasia and Athletic Record, 1906)

See also Jack Lalanne.