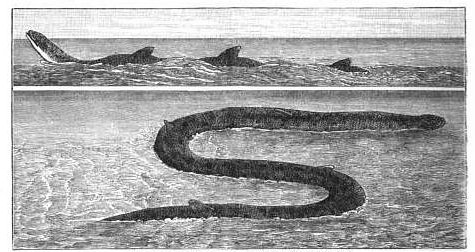

On May 13, 1872, the barque St. Olaf was sailing from Newport to Galveston when a crewman called out that “he saw something rising out of the water like a tall man”:

On a nearer approach we saw that it was an immense serpent, with its head out of the water, about 200 feet from the vessel. He lay still on the surface of the water, lifting his head up and moving the body in a serpentine manner. We could not see all of it, but what we could see from the after-part to the head was about 70 feet long, and of the same thickness all the way, excepting about the head and neck, which were smaller, and the former flat like the head of a serpent. It had four fins on its back, and the body of a yellow, greenish colour, with brown spots all over the upper part, and underneath white.

The weather was calm, the sea smooth. “The whole crew were looking at it for fully ten minutes before it moved away,” Captain A. Hassel reported later. “It was about 6 feet in diameter.”